By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten New York correspondent

New York has often been derided as a playground for the rich, with their empty glass towers and breathtaking views of the city that most of us could not afford in three lifetimes. Perhaps I’m being too harsh towards those whose financial contributions to cultural institutions, tax revenue, and quality of life have benefited society. One such benefit are privately owned public spaces or POPS, that provide public space amid the density and pedestrian shortcuts on those long Midtown blocks.

There are nearly 600 such “parks” across the city and you can discern them by their tree in a box logo rather than the Parks Department’s maple leaf in a circle. The light fixtures and seating also do not conform to the city’s street furniture catalog.

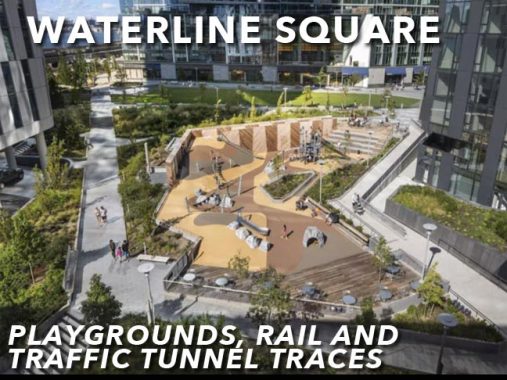

While Kevin observed New Years Day 2021 at Moynihan Train Hall, I took my children to a playground that has a huge sloping pit on the final block of the two-decade Riverside South development. The rubber surface allows for easy climbing and running, certainly something different from most city playgrounds that are built on flat surfaces. The design firm, Landscape Structures, also worked on Lincoln Terrace Park, Chelsea Green, and Domino Park, among other sites in the city.

Parents can sit on oversize wooden steps overlooking the pit, giving children the freedom to explore. Most Instagram posts of Waterline Square focus on the glass towers but from another angle one can admire the Beaux Arts design of the landmarked IRT Powerhouse.

The 3-acre park also has a lawn, fountain, seating area, and a constructed stream that cascades towards the Hudson River. On my visit the streambed was empty but promotional photos for Waterline Square show a postmodern eden of children exploring the constructed landscape. The view of Hudson River is disrupted by the Henry Hudson Parkway, which has an elevated section between 59th and 72nd Streets. This is the only portion of the old Miller Highway that was reconstructed, with the rest of it transformed into a boulevard that was built in tandem with Hudson River Park from Battery Park to 59th Street.

There is a tunnel designed for the highway beneath Riverside Boulevard as seen in this 2008 photo. In the 1990s, Rep. Jerry Nadler had a feud with Donald Trump, whose name appeared on some of the towers on this boulevard. Rather than to pay for it and enhance the value of his development with an underground highway, Nadler preferred to give Trump’s clients a view of the elevated highway. Portions of this tunnel are complete but who knows when they will see vehicular traffic? The precedent for such a tunnel under a park can be seen crosstown at Carl Schurz Park, which covers FDR Drive.

The connection between the tunnel and highway was never built. Looking north at Riverside Boulevard, it is not clear where the highway would enter its tunnel and how it would do so without disrupting the polite scenery of Waterline Square and Riverside Park South. In a city of many unused subway tunnels, this is the only highway tunnel that was built but is not in use.

Although this development occupies two blocks of the Manhattan grid, it preserves the sight line of W. 60th Street. During the warm months, a fountain on a tic-tac-toe grid appears on this plaza.

Along with Riverside Boulevard, Freedom Place South was added to the map after the turn of the millennium. Perhaps to calm traffic or make for dramatic scenery, this street takes a winding route through the neighborhood. The top ten levels on Bjarke Ingels-designed Via57 pyramid have an intentional unfinished appearance giving it a constructivist look that exposes the building’s framework.

At West 62nd Street and Riverside Drive South is a verdant plaza built above the Amtrak line that was covered by this new neighborhood. The tracks were preserved in place with the land on either side being raised and then a deck constructed for the streets, towers, and parks of Riverside South.

The highway tunnel under Riverside Boulevard isn’t the only unrealized transportation item near Waterline Square. Below the plaza on Freedom Place South, the Amtrak tunnel widens a bit for a platform. Until 1916, the Hudson Line had stations on the West Side at Manhattanville, 152nd Street, Fort Washington, and Inwood, but subway service made them redundant. When this line was decked, the platform was built for a future station at West 62nd Street to serve the Upper West Side, and another station at Manhattanville.

To have Amtrak share its line with Metro North requires the cooperation of multiple public agencies so the bureaucracy alone will take decades to resolve and then perhaps another decade for a staircase to the street. In the meantime the priority for Metro North is to have its New Haven trains access Penn Station using the Hell Gate Bridge.

Concerning railroads, the entirety of Waterline Square and Riverside South was a massive railyard into the 1980s, after which it was occupied by a parking lot until the early twenty-teens. Prolific city photographer Percy Loomis Sperr stood on the corner of West End Avenue and 60th Street in 1930, capturing the spot where the Hudson Line continued south in the middle of the road, on what locals called Death Avenue. By 1934, the section between 60th Street and Penn Station was relocated to a trench running midblock between 10th and 11th Avenues. Nearly the entire trench would be decked by buildings in the following decades, transforming it into a subway.

If Sperr were to time travel to 2021, he would see self-powered skateboards, Citi Bikes, electric unicycles, mopeds, hybrid buses, but no flying cars. There are still plenty of other wheels turning on the site of the former railyard at this Soulcycle location. Schools here are vertical with outdoor space on rooftops, such as the Heschel School and P.S. 191 a block to the north and CUNY John Jay College a block to the south. Would Sperr recognize where he is standing? Perhaps as he looks north and sees the hill on West End Avenue.

If you liked the essay on Waterline Square, continue north to Riverside South for more postmodernity atop a covered train line. You can also see similar architecture and POPS at Hudson Yards.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

1/6/21