By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

THE largest historic mansion in the Bronx is the Van Cortlandt House in Riverdale, namesake of the 1146-acre park in which it stands. Every time that I revisit this building, I find something that I hadn’t seen before. Certainly safe from demolition, the mansion was sold to the city by the Van Cortlandt family in 1889 and has been preserved ever since as a museum.

When it was built in 1748, New York had been a British colony for 84 years. The population was diverse and English was the main spoken language, but Dutch remained popular. Like the seigneurs of Quebec, the patroons of New Netherlands maintained their feudal estates, language, political power, and culture under British rule. In the Van Cortlandt House the west parlor room celebrates the family’s heritage with the orange and blue colors that appeared on the old Dutch flag. Those colors appear on the flags of the city and the Bronx. Their wealth is evident in the furniture and china dishes on display.

I could write about the Dutch doors that allowed in the wind while keeping wildlife out of the house, the bedrooms and parlor rooms, but this is Forgotten New York, so I descended to the basement…

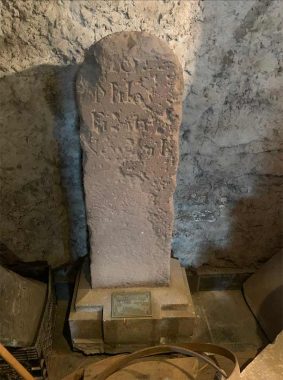

Battered by weather and carelessness, the milestone that stood on the Albany Post Road, 18 miles north of its beginning in downtown Manhattan, was relocated to the mansion in 1934, initially outdoors and later to the basement. Most of its route became Broadway or the U.S. Route 9 in New York. But the colonial route was curvy and Kevin documented two of its original segments, Old Albany Post Road and Albany Crescent.

Outside the mansion is a piece of a brick wall with a barred window. It was part of the Duane Sugar House that stood on the site of One Police Plaza. The Van Cortlandts made their wealth from sugar, among other crops. During the American Revolution, that building was used by the British as a prison. After the old building was demolished in 1892, one of its windows was kept on site and later incorporated into the NYPD headquarters, while another window was installed in the yard of the Van Cortlandt mansion in 1903 as a memorial to the imprisoned patriots.

Above the windows facing south, alongside the main entrance are a set of grotesques. Unlike gargoyles, which are based on animals, grotesques are disfigured likenesses of humans. As an alumnus of CCNY, I’ve seen plenty of them on that historic campus.

Also on the southern side of the mansion is a millstone embedded into the pavings. This mill stood at the outflow of Van Cortlandt Lake. It reminded me of a similar situation at Queens Plaza, where a millstone was encased in concrete, and later became the centerpiece of a park, Dutch Kills Green.

Returning to the basement, I walked into a room full of tools relating to cooking. This is where food was prepared for the Van Cortlandt family, their guests, servants, and slaves. I can imagine the house in colonial times as a hub of activities. It was a residence, farm, and stop on the road between New York and Albany. Concerning forced labor, in recent years the mansion and the Parks Department installed signs and renamed places around the city to commemorate the roles of Black individuals in the city’s history. Van Cortlandt Lake, a millpond built by slave labor, was renamed Hester and Piero’s Mill Pond in 2021, in honor of one slave couple that worked on the manor.

Being the “hidden waters” historian, I appreciated a sign mentioning Tibbett’s Brook, the stream that flowed to the south of this house that was partially channeled into a sewer. There is a campaign to have it daylighted and flowing in the open again to the Harlem River.

Speaking of urban streams, the map of 18th-century Amsterdam on the wall fascinated me. How many of those canals are still there today? Does the Dutch capital have its version of Forgotten New York?

On the top floor, a door opens into an attic where the walls are not painted and there is no heating. Until recently, this was a storage space unworthy of public attention. With attention given to the slaves who made this farm profitable, the attic was restored to its likely purpose during the colonial period: the slaves’ room.

Never having visited a prison, concentration camp, or a southern plantation, this was my first experience seeing how people lived in captivity. The beds look like shelves with sheets on them. There are no windows. Looking up at the roof, there’s no insulation. Meanwhile every other room in this mansion: bedrooms, parlor rooms, kitchen, had fireplaces. It must have been a horrific experience.

As Central Park had Seneca Village, Van Cortlandt Park has a slave cemetery near the mansion. But did anyone try to flee from the manor? In the summer of 1733, Andrew Saxton fled from Jacobus Van Cortlandt, who then advertised for his capture in the New-York Gazette. The master was affiliated with the Dutch Reformed Church, but Saxton professed himself a Roman Catholic. Before other freedoms were granted by law, religion was the first to be recognized. Many of New York’s early slaves were taken from Africa by Spanish and Portuguese traders, and baptized in the Catholic faith, before they were sold on Wall Street to local merchants. We do not know if Andrew Saxton was captured or escaped successfully into the anonymity of history.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

1/14/23