I have a number of Crosstown posts lined up as there are still hundreds of east-west NYC streets to be covered, and I now have a backlog of photos that will keep FNY busy in this category. Last week, I easily handled Leonard Street in Tribeca and so it was an easy matter to turn around at Collect Pond Park and head back west, down Franklin Street, which has borne that name in honor of Revolutionary-era statesman and patriot Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) since 1777, when he was still around. Franklin is also represented by Franklin Avenue in Morrisania in the Bronx, Franklin Street in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, Franklin Avenue in Brooklyn where Clinton Hill meets Bedford-Stuyvesant, Franklin Avenue in Flushing, Queens, Franklin Avenue in New Brighton, Franklin Lane in Richmondtown and Franklin Place in Castleton Corners, Staten Island. A statue of Franklin, originally a printer by trade, stands in what used to be called Printing House Square at Park Row and Spruce Street, seen here. More obscurely, Franklin’s likeness can be seen on a cast iron front building at #63 Nassau Street, which I have on this page. The printer, diplomat, scientist and negotiator’s portrait is on the $100 bill and formerly, the rarely-used 50¢ coin.

The first building you see when walking west on Franklin Street is this marvelous old Romanesque two-toned sandstone building on the corner of Lafayette, with three large combination arched oriels in the front. Known as the Ahrens Building, as the property was originally owned by liquor dealer Herman Ahrens, who erected the building in 1895.

West of Lafayette Street a narrow alley, unmarked by a street sign and covered by a ubiquitous construction shed, heads north from Franklin Street.

There are places where Lower Manhattan’s old grittiness pokes through. Cortlandt Alley is unusual among Manhattan alleyways in that it runs for three blocks. You can occasionally find some that run two blocks — like Staple and Collister Streets on the west side of Tribeca — but three is a king’s ransom. The alley goes all the way back to 1817, when local landowners John Jay, Peter Jay Munro, and Gurdon S. Mumford laid out the narrow lane through properties between Broadway and what would be Elm Street (which is now a part of Lafayette) and White and Canal Streets. If this 1830 map accurately reflects the reality back then, the alley might well have run along the stream leading into Collect Pond, which was soon to be placed in a canal today’s Canal Street runs over. In any case, the original Cortlandt Alley presented a rural aspect much different from the one seen today.

The section between Franklin and White was laid out in the 1820s and lies 25 feet farther west than the original section. It was named for a Dutch nabob, Jacobus Van Cortlandt, one of the original European landowners in these parts; the alley, Cortlandt Street, Jacobus Place in Marble Hill, and all the Van Cortlandts this and that in the Bronx, including the mansion and the park, all spring from that family. The mercantile structures we find lining it go back to after the Civil War, when Lower Manhattan’s trade really picked up.

Just off Franklin, a heavily graffitie’d metal door beckons with a couple of tiny openings. What could be inside?

In what was once a freight elevator in a paper warehouse fronting on Broadway, is the city’s smallest and likely most unusual museum, called simply Museum. Much like Brooklyn’s City Reliquary, its mission is to display found objects and unusual collections, doing so in a cozy, welcoming, well-lit space. The museum’s curators say the exhibits will constantly be changing throughout its operation, but when I got insiade some years ago, the exhibits included mislabeled food containers collected by sous-chef Lulu Kalman, global toothpaste collection of industrial designer Tucker Viermeister, Polaroid photos discovered by artist Andy Spade, lost objects found on the bottom of the Pacific by deep-sea diver Mark Cunningham, and more. There are also two video screens playing works by filmmakers Richard Sandler and by the NYC documentarian Joey Boots, who has passed away since.

Other eclectic objects from around the globe, found by submitters, include Russian watches, matchboxes, paperweights, nameplates from the UN General Assembly, magazines, food labels, a cap worn by someone pretending to be a surgeon in a hospital and witnessing an operation, business cards, and an assortment of weird hammers and saws.

Admission is by appointment at MMuseumm.com. Closed for the season in March 2024, it is due to reopen in the spring.

It was a bit easier to see inside the Stephen Friedman Gallery at Franklin and Cortlandt, which was closed on a Saturday. The current exhibition was by British artist Sarah Ball, whose show “comprises a new body of paintings exploring notions of dandyism in the 21st century.”

A building teardown on the south side of Franklin permits an interesting perspective on a couple of Broadway classics. #361, on the corner of Franklin, is an ivory colored cast iron front James. S. White Building, constructed in 1882. Next to it is the much shorter #359 Broadway, an Italianate built in 1852. When it was new, famed potrait photographer Mathew Brady occupied the top three floors.

Since #367 Broadway on the corner of Franklin is outside a landmarked district, and Tom Miller, the Daytonian in Manhattan, doesn’t mention it, I don’t know much about the building which is home to the bridal dress designer Jaxon James. In fact, a bride within was modeling a dress, but I aimed the camera elsewhere, discretion being the better part of valor. Actually I have become quite interested in sidewalk shingle signs, which are often found in “arty” or “hipster” realms, but I find their designs fascinating.

The pineapple is often used as a decorative motif. The fruit (my favorite fruit actually) was brought to Europe by Columbus, where the natives in the island of Guadeloupe gifted him with several.

During the 18th century, the pineapple was established as a symbol of hospitality, with its prickly, tufted shape incorporated in gateposts, door entryways and finials and in silverware and ceramics. [Smithsonian]

Between Franklin and White Street west of Broadway is Franklin Place, which I’ve examined in detail in FNY.

Franklin Place, originally called Scott’s Alley and later renamed to honor Benjamin Franklin, runs parallel to Broadway between Franklin and White Streets; it comprises a portion of the boundary of the historic district.

It was originally laid out on land owned by Henry White, James Morris, and others, and in 1809 was extended northward to Canal Street through the land of John Jay and Peter Jay Munro. [LPC Tribeca East Designation Report]

Naturally I picked out the lone brickfaced building, #74 Franklin, on a block full of cast iron fronts. It was built in 1815 for merchant John Wood.

I was surprised to find a bakery, Billy’s, at #75 Franklin across the street, which was built in 1865 and attained its present Romanesque appearance in 1891. Reviews vary widely but are mostly good. One of my most profound regrets is that I cannot run wild in bakeries, especially now because I picked up 10 pounds of winter weight just by being at my desk or on my couch and adding in some potatoes, rice and pasta that I now have to work and diet off. Life ain’t fair.

At #76, we find Twenty First Gallery, which purveys “collectible design” consisting of chandeliers, mirrors, chairs, cabinets and coffee tables, but this isn’t Raymour & Flanagan: the pieces are definitely “arty.” One again, I liked the sparely-designed sidewalk sign.

81 Franklin Street was constructed in 1861 by builder John Sniffen, who is also associated with Sniffen Court, the private enclave uptown in Murray Hill on East 36th Street between 3rd and Lexington where the cover of the Doors’ LP “Strange Days” was shot. (I really have to get better photos of Sniffen Court as I have not been there for a couple of decades). Upscale lighting dealer Allied Maker occupies the ground floor.

I’m at the point in life when I’m particularly vulnerable to shingles, a painful condition that anyone who had chicken pox as a kid can get. My chances decreased, though, when I got a pair of Shingrix shots. I’m still vulnerable to shingles, though, since I liked these cleanly designed sidewalk shingle signs for various art galleries arrayed along Franklin Street.

At a time when running water and adequate plumbing in tenements was scarce in NYC, there were hundreds of public bathhouses scattered around, some of them houses in fanciful classical style buildings. As conditions improved, most of them disappeared and their buildings repurposed. AIRE, at #88 Franklin, bucks the trend:

In the midst of the bustle and fast-paced rhythm of downtown, right at the heart of TriBeCa, there is an oasis of tranquility exclusively designed to balance mind and body. Located at a restored historical building, originally an 1883 textile factory, the AIRE experience consists of an unforgettable journey through sensations across the various baths with water at different temperatures that will transport you to the ancient times of the Roman, Greek and Ottoman traditions. [AIRE}

I’m not sold and will continue to use my washbasin in the kitchen every Saturday. Just kidding.

As I’ve said, I like a good brick building, and the new #100 Franklin Street, where 6th Avenue begins its march north to Central Park. The complex consists of a pair of triangular buildings, one of which touches on White Street and doesn’t touch Franklin at all. (To me, the builders dropped the ball when they didn’t call it #1 6th Avenue; the nearby Roxy Hotel is #2 6th.) Some of the apartments, which can sell for the mid to upper 7 figures, are wedge-shaped!

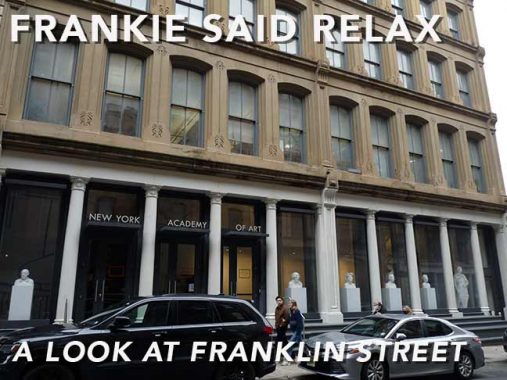

The New York Academy of Art is a private art school at #111 Franklin Street, commissioned by Daniel Appleton & Co., book publishers, and built in 1868. The school was founded in 1980 and began operating here in 1990, persevering through a devastating fire in 2001. In the window, I found busts of Andy Warhol (I initially thought it was Fran Leibowitz) , Jean-Michel Basquiat, Salvador Dali and Frida Kahlo.

One of the rustier cast-iron fronts at #116-118 Franklin, was designed by Griffith Thomas and finished in 1872.

I have featured this entrance kiosk at the downtown Franklin Street IRT 7th Avenue Line (#1) station before, but it’s unique in the system. It was built in the 1990s during station renovations to shield passengers from the rain in this open plaza at West Broadway, Varick and Franklin Streets when entering and exiting. The platform mosaics feature unusual paneling and floor tiling that are unique to the system. When Aretha Franklin passed away in 2018, the MTA added “Respect” stickers to the walls in the same style as its black and white Helvetica standard signage.

Instead of taking Franklin all the way west to Greenwich Street, it was raining and I decided to cut things short, but I wanted to check on some Tribeca items, thus walked north on Varick. I found this pair of signs that represent two different signage philosophies. For decades, traffic signs were done in ALL CAPS, but a new philosophy, now mandated by the Feds, holds that upper and lowercase lettering is more legible. So, the sign on the bottom is newer than the sign on the top. Both are in Highway Gothic; the Department of Transportation had a decade-long flirtation with Clearview, an ugly substitute in my humblest of opinions.

The corner store at what the owners call 235 West Broadway (which is apparently a sexier address than #2 White) is officially a Todd Snyder men’s store, and a glance in the windows will make apparent that it’s a haberdasher. In recent years, it’s fashionable to not hang an identifying sign whatever–you have to go in to find out what the name is.

Signs of the store’s former use are still very much in evidence. In 1941, Leonard Hecht opened a liquor store on the ground floor that continued in business until the 1990s. The Liquor Store Bar then took it over, then J. Crew in the 2000s and now Todd Snyder. Throughout, the old neon and etched glass liquor store signs have been permitted to remain in place.

Because of the miracle of landmarks preservation, the designated #2 White Street, at the northeast corner of West Broadway, has survived since 1809. It was constructed that year for a Gideon Tucker, owner of the Tucker & Ludlam plaster factory. It’s one of the few Federal Style row houses remaining in lower Manhattan. A few others that were moved from their original location during construction of Independence Plaza can be seen on Harrison Street west of Greenwich.

Above it is a painted ad for the defunct Matera Canvas, which distributed boat covers, tarpaulins, tote bags, awnings, aprons at 5 Lispenard Street, originated in 1907 and was still in business in 1990.

One of the few remaining 1910s-20s era Twinlamps not on 5th Avenue is still soldiering on here at 6th Avenue and Walker Street. The DOT actually removed it a few years ago, and I feared the worst, but it was repaired and repainted and put back in place. I do wish, though, it could be given a couple of retro Bell fixtures, as well as get a replacem ent finial at the top. It’s still leaning over, too.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link.

3/24/24