This time, as we open the ancient New York City Street Necrology with its cracked, crumbling leather cover, a dogeared page with running, streaming ink and stains from lord knows what plops open, and there, revealed on the verso, is…Fourth Avenue, and there on the recto is Avenue A.

Today, Fourth Avenue is the shortest numbered north-south avenue in New York City. With its tilt athwart the other NYC avenues, it’s also the only “north-south” numbered avenue in NYC that approximates true north. (You can prove it with a compass.) Just as the planet Pluto’s orbit was shown to be out of alignment with the other eight planets, so Fourth Avenue is the joker in the deck of NYC north-south avenues.

As presently constituted, Fourth Avenue runs only a scant six blocks, between Astor Place on the south to East 14th Street and Union Square at the north. The short section between East 4th Street and Astor Place is designated by NYC street signs as being part of Cooper Square, and we’ll hew to that designation here.

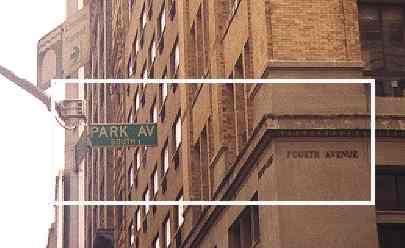

North of Union Square, Park Avenue South and further north, Park Avenue, take over Fourth Avenue’s slot.

Park Avenue South and Park Avenue, though, in the dim past were once known as Fourth Avenue. as the building on Park Ave. S and East 23rd Street indicates.

So, why was Fourth Avenue renamed? The answer lies in the politics of railroad building in Manhattan.

In the 1830s, the new iron horse was already the rage, and railroad builders scrambled to get a piece of the action. By November 1832 the New York and Harlem Railroad had laid (lain? we’re not sure) tracks along the Bowery from Prince Street as far uptown as 14th Street and was bargaining to extend northward. This early version of the iron horse was pulled by real horses–because of city regulations fearing the then-new steam engine technology.

When the NY&HRR attempted to get clearance to run steam locomotives, the city designated Fourth Avenue, then existing only on planners’ drawing boards, as an appropriate route. The railroad dynamited the steep granite ridge that ran along Fourth Avenue’s future route and laid tracks in a barely-covered cut.

Smoke and steam from the NY&HRR continually belched up from the depths, and no one but the poorest shack dwellers and gangs such as the Fourth Avenue Boys would live in the area.

The 1847 map at left shows the NY&HRR extending from Centre Street north along the Bowery and Fourth Avenue.

NY railroad historian Joe Brennan:

The NY&H started at Park Row and Centre St from the beginning. Prince St may have been the uptown end of the first section, I can’trecall. I think Prince St was a station for a while, i.e. a place with a ticket office. I can check this but the main point is that Prince St was not the downtown end.

The 1847 map should show it extended down Park Row to end at Broadway (not actually entering the sacred soil of Broadway itself of course).

The point that looks wrong is that it ran in Broome St only downtown; it ran uptown in Grand St. I would have to look this up to see whether it was only Broome at an early date as shown. There are numerous postcard views of the Bowery photographed from Grand St el station, and you see three tracks in the first block, which are the Third Ave RR pair and the uptown N Y & Harlem. A close look will reveal the fourth track curving in at Broome St a block away. NY&H had the center pair because they were there first. From Broome to 6 th St, Bowery had fourstreetcar tracks. This is probably one reason the el was built overthe curbs, to avoid spanning four street tracks that were too close to put el pillars between them.

New York City government eventually had enough of the smoke, the steam, the racket and the Fourth Avenue Boys, and gradually passed edicts limiting the southernmost point at which steam engines could go. Eventually, that point became East 42nd Street, and eventually, that led to the construction of the first Grand Central Terminal in the 1880s.

Until the trains ran underground, the blight continued. Some time in the 1850s, the railroad did cut a tunnel beneath Fourth Avenue between 33rd and 38th Streets, which still exists for auto traffic today. That tunnel was covered with a landscaped garden, and Fourth Avenue became Park Avenue from 34th to 38th in 1860.

The Park Avenue moniker became used by the city as a way of promoting, or perhaps encouraging, the railroad to move underground, and by 1867 Fourth was renamed Park as far north as 42nd Street. By 1888, the railroad had been moved underground as far north as 96th Street, and the avenue got the Park Avenue designation.

In the Bronx, various streets along the New York Central (which had bought up the NY&HRR) were also renamed Park Avenue in 1896, so today Park Avenue goes as far north as Fordham Road. Similarly the Park Avenue name crept south from the railroad tunnel, and by the early 20th Century Fourth Avenue south of it became Park Avenue South. Numbering of Park Avenue proper begins at East 32nd Street.

Since the change to Park Avenue South (in what was probably a bid by NYC to shine up this part of the street and remind people of the broad, handsome boulevard it had become north of GCT) was slower in coming, some buildings along Park Avenue South still bear the old Fourth Avenue name.

The still-existing section of Fourth Avenue, between Cooper and Union Squares, also has a lengthy lineage, one that goes back to a Native American trail that was adopted by the Dutch, who called it, in an English translation, the Bowery Road.

The Bowery Road stretched from today’s Chatham Square all the way north to a fork in the road at today’s 22nd Street. From there, the Bloomingdale Road went north, while the Eastern Post Road stretched northeast. It ran all the way to East Harlem, where it was connected by ferry to other roads that became the Boston Post Road–today’s U.S. Route 1. The Manhattan section of Eastern Post Road was closed between 1839 and 1844, while Bloomingdale Road was absorbed into Broadway. Today’s Fourth Avenue is a remnant of the old Bowery Road.

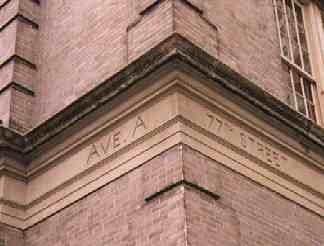

Public School 158, York Avenue and East 77th Street

One block east of 1st Avenue is a north-south thoroughfare that goes by different names depending on what part of town you are in.

Between East Houston and 14th Street, it’s called Avenue A, but further uptown it’s York Avenue and other names.

As originally laid out on the Randall plan of 1811, it was Avenue A all the way uptown. Obviously, though, things have changed.

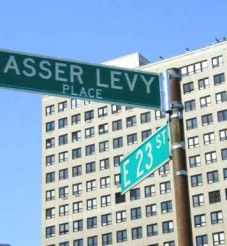

A stretch of Avenue A, between East 23rd and East 25th Street, was cut off from the rest when Stuyvesant Town and Cooper Village were constructed in 1947. It was renamed Asser Levy Place, for one of NYC’s first Jewish settlers. Governor Peter Stuyvesant tried to bar him from the city militia, but Dutch West India Company directors in Amsterdam upheld Levy. The city renamed Avenue A for him in 1954.

Between about East 26th Street and East 53rd Street the Manhattan riverside bends inward and there is no room for Avenue A, but it once again appeared at East 53rd and runs north to another inward turn of the East River at East 92nd Street. It is known as Sutton Place, for dry goods merchant Effingham Sutton, north to East 59th Street.

Avenue A kept its name from East 59th to East 92nd Streets, until 1928, when it was named for World War I hero Sergeant Alvin C. York, who refused to capitalize on his winning the Medal of Honor, saying “this uniform ain’t for sale.” He used profits from the 1941 biographical movie starring Gary Cooper to open a school for children of his native Tennessee.

One more brief stretch of Avenue A remained to be renamed, east of Avenue A in East Harlem. It was renamed Pleasant Avenue in 1879.

Sources:

Naming New York, Sanna Feirstein, NYU Press 2001

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

Street Book, Henry Moscow, Hagstrom 1978

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

In Old New York, Thomas Allibone Janvier 1894, reprinted 2000 St. Martins Press

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

As You Pass By, Kenneth Dunshee 1952 Hastings House

Out of print