Early British colonists in Maspeth were chased out by angry Native Americans, and found themselves where Queens Boulevard meets Broadway today. There they met a possibly more implacable foe…the Dutch, who had this thing about naming places in Dutch, and the Brits were forced to call their new settlement Middelburgh (or Middletown). That name persists as Middle Village south of Elmhurst; eventually, the name Newtown was applied to the new town. Horse cars and eventually streetcars began to bring in people from all over, and when Cord Meyer developed the area in he 1890s, he lobbied for a higher class name…Elmhurst. Strangely, the IND subway, which arrived in 1936, keeps the Newtown name.

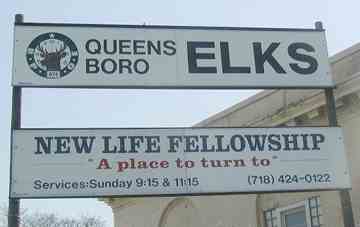

Any discussion of the architecture of Elmhurst begins with the Elks Lodge Local 878 on Queens Boulevard and about 51st Avenue.

It was once the largest Elks Lodge on the East Coast, with 60 rooms, bowling alleys, billiards, a ladies lounge, and a 50 foot bar (this was built in the teeth of Prohibition in 1924!)

The Ballinger Company designed the granite, limestone and brick structure dominated by a now-verdigris-covered elk at the front entrance.

We have the Elks Lodge, we still have the Lions Club and then there used to be the Loyal Order of Moose in Astoria.

In recent years, The Elks Lodge has been home to Extreme! Championship! Wrestling! The organization was bought out by Vince McMahon a couple of years ago, but its brand of hardcore grappling has been highly influential.

The church purchased the main lodge building at 82-10 Queens Blvd. Elks Lodge #878 continues to meet to hold meetings at 82-20 Queens Blvd which is owned, not rented by BPOE #878.

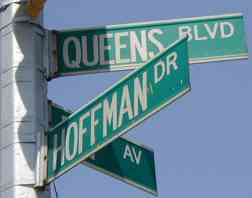

A nearby street doesn’t forget the heritage.

One of the first religious buildings in Newtown was the old St. James Episcopal Church at Broadway and 51st Avenue. It is a relic of colonial rule, having been chartered by George III and erected in 1734: it is Elmhurst’s oldest remaining building. It formerly supported a clock tower that a storm blew down in 1882. Last used as a church in 1848, it is now a community center and Sunday school, although the over-265-year-old building is in need of much repair. A ‘new’ St. James, built in 1848, burnt down; its replacement is an unremarkable brick building catercorner to this one.

Directly across the street from old St. James is the Reformed Dutch Church of Newtown, built in 1831, enlarged in 1851 with stained glass added in 1874. It replaced an older structure built in 1733. On the Corona Avenue side is an ancient graveyard with some Dutch stones.

Justice Avenue is one of the oldest roads in Elmhurst, dating to the colonial era. The traffic island where it meets 90th Street and 56th Avenue, has been piquantly named by The Parks Department under the imaginative auspices of Henry Stern as ‘Horse Brook Island.” There are no horses or brooks here any more, but when the area was first settled, a short creek named Horsebrook flowed from this spot to approximately Kneeland Avenue and Grand, about six blocks to the west.

One of the most distinctive buildings, with five spires, in Queens is Newtown High School at Corona Avenue and 90th Street. It was designed in a Baroque style by C.B. J. Snyder and built in 1897.

FLIGHTS OF FANCY

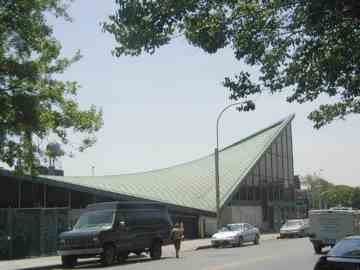

George Jetson would feel at home in this setting. Take this North Fork Bank building at about 55th Avenue. Designed and built for Jamaica Savings Bank in 1968 by William Cann, it sort of looks like a Stealth bomber a couple of decades before the bomber appeared.

In the Swingin’ Sixties, Queens Boulevard in its Elmhurst stretch became experimental territory for ambitious architectural firms stretching their wings, inspired, no doubt, by the New York’s Second World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows in 1964 and 1965. As a matter of fact, Queens Boulevard for a few blocks is much more experimental than Manhattan, where architects have usually played it pretty safe.

The World’s Biggest Store had previously got into the ambitious architectural act in 1965 when Skidmore, Owings & Merrill designed this (roughly) circular building surrounded by a parking garage. But a lady named Mary on Queens Boulevard and 55th Avenue almost scuttled the whole thing.

Macy’s bought up all the real estate in the irregular block bounded by Queens Boulevard, 55th Avenue, 56th Avenue and Justice Avenue to build a new store here… all of it except the corner of Queens and 55th, where Mary Sendek’s house and property stood. Mary and her husband Joe Sendek had bought the property in 1922 and had been there ever since, and Mary continued to live there after Joe died and the kids had moved out. The house was her life, and she couldn’t be budged, even after Macy’s offered her five times the value of the land! Defeated, Macy’s simply cut a notch in the new building to avoid the Sendek property. When Mary died in 1980, her estate sold the property and a commercial building now stands on the site.

Ironically, Macy’s was also forced to amend their flagship location in Herald Square in 1902 when a rival store, Siegel-Cooper, bought a small building at Broadway and 34th Street. That building was razed and a new 5-story building was built in its place in 1909, which stands today… supporting a giant Macy’s sign.

Circular buildings became a trend on Queens Boulevard. This former (now unoccupied) European American Bank was torn down just a few weeks after the Forgotten NY Olympus D490 captured it.

It looks like a Frank Lloyd Wright, but it’s not. This is the handsome Elmhurst Library branch on Broadway at 51st.

This Beers property map of Newtown from 1873 shows Hoffman Boulevard as the thick line that stretches across the middle of the map. Note the slight curve in the center of the map: Newtown Turnpike (57th Avenue) intersects it from the west, while Trotting Course Lane (now Woodhaven Boulevard) angles off to the bottom. Justice Avenue curves along a now-vanished railroad at the top; Justice Avenue’s present-day angle is due to the old railroad.

Below: Queens Boulevard at about 63rd Street, late 1930s

THE ROAD OF QUEENS

For all of America’s casting the trappings of British monarchy aside after 1776, both Brooklyn and Queens contain main roads named for royalty, and the borough itself, and its main artery, are named for a 17th-Century Portuguese princess who married England’s Charles II.

Now a pedal to the metal, multi-lane behemoth, Queens Boulevard, which runs from Long Island City to Jamaica, was once a swampy dirt road known as Old Jamaica Road and Hoffman Boulevard until it was drastically widened and blacktopped in the 1910s with the advent of the automobile.

Here and there, though, as with many of New York’s main roads, there are traces there of the roads’ former paths before they were straightened out. The short road shown above meanders away from Queens Boulevard at about 57th Avenue and returns at aboutWoodhaven Boulevard. It is an unstraightened section of the original road.

The short, curved road, known as Hoffman Drive, is now a vestige of old Hoffman Boulevard. It was kept after Hoffman Boulevard was transmogrified into the monster now called Queens Boulevard. This is the original Queens Boulevard.

Though the Elmwood has now retired, its neon sign is still there. But for how long?

Queens Boulevard has acquired the moniker “Boulevard of Death” in recent years, as motorists craving speed and power routinely treat the wide road as if it were a NASCAR course, with frequent pedestrian fatalities. The helpful Department of Transportation, instead of aggressively enforcing speeding statutes, or dramatically lengthening green lights, has installed signs at intervals along the boulevard that place the burden of safety on the pedestrian, not the motorist. Some signs even say ‘pedestrian killed at this corner’.

The best solution would be to reduce Queens Boulevard to a six-lane road and build under- or overground passageways at several key crossings, or depress it without cutting off Queens neighborhoods from each other, as frequently happens when open-cut highways are built.

At-grade highways are an anachronism that increasingly call for remedy.

Hoffman Drive, until recently, boasted one of NYC’s dwindling number of neighborhood theatres, the Elmwood…with a marquee that actually had letters that a guy had to put up with a ladder. The Elmwood’s name is likely a portmanteau of Elmhust and Woodhaven.

Here and there, vestiges of the old Hoffman Boulevard remain. This rug store, or rather the building that hosts it, likely dates to the early part of the century.

Elmhurst Baptist Church, Whitney Avenue near Judge Street, features unusual stone construction.

Christian Testament Church, nearby on Whitney Avenue…

The word Mizpah above the door features several Old Testament connotations.

SOURCES:

New York’s Architectural Holdouts, Andrew Alpern and Seymour Durst, Dover Publications 1984

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

6/24/02