Sometimes, I’d rather be in Philadelphia. Or Boston. Or even Albany, Newark or Jersey City. I’ll explain. Manhattan, once you get north of 14th Street, just doesn’t have the sheer number of dead-ends or one-block alleys block by block that other northeast cities have. Philadelphia has a main network grid of streets — numbered north and south, named east and west — and in between the grid is a cheesecloth of narrow alleys, some with Belgian block paving, some lit by methods last seen in the early 20th century. Boston has several lanes that are mere cracks between buildings. All of them have names, and the smaller alleys that issue from the ‘bigger’ alleys have names, too. When I was in San Francisco in 2008, I marvelled at its network of alleys (many of which I shot and they’ll find their way online, someday).

Of course, if you check out FNY’s Street Necrology of Lower Manhattan, you find that many downtown Manhattan alleys, like the Neanderthal in Europe, survived until relatively recent times. The relentless push of development, like the relentless technological advances of Homo sapiens, doomed Manhattan’s alleys as surely as the Neanderthal were doomed. (Further delvings, into sites like Gilbert Tauber’s Oldstreets, will reveal that even more strange alleys were once found on Manhattan Island, attached to streets that have changed names repeatedly before the current names were settled upon, or vanished entirely.)

As Manhattan evolved out of its early alley period, so too did downtown Brooklyn (I include DUMBO and Brooklyn Heights in the overall region). And, once again, a peek at FNY’s Downtown Brooklyn Street Necrology reveals dozens of dead ends and one-block lanes that have been done away with by expressways, housing projects, and other buildings whose developers got whole swaths demapped. Though I thought Brooklyn’s colonial-era Red Hook Lane was under the gun in 2004 when I thought its destruction was imminent, it’s still there — perhaps the miserable economy has caused the developers who sought to build over it to delay their plans.

So I went unsteadily careening through downtown Brooklyn, DUMBO, and Brooklyn Heights one Saturday a year and a half ago (writing this in June 2010) no doubt frightening the nouveau riche and cool hipster kids on their way to Jacques Torres Chocolates and Galapagos, yanking out the ForgottenCamera every time I spied a surviving dead end or long-forsaken, one-block alleyway.

High Street-Red Cross Place

High Street used to run for eight blocks from Fulton Street east to Navy between Nassau and Sands Streets, but has been repeatedly truncated over the decades, first by the new Manhattan Bridge approach in 1909, and then by the 1930s Farragut Housing project and then by the new Cadman Plaza in the late 1950s. Today, two pieces exist: a short block between Pearl and Jay Streets in the Manhattan Bridge shadow, and then renamed Red Cross Place (above) between Cadman Plaza East (old Washington Street) and Adams Street, itself rebuilt as a multi-lane Brooklyn Bridge approach.

At one time the American Red Cross had a headquarters in the vicinity, as shown by this painted sign in the IND station, but the Red Cross is now at 200 Schermerhorn Street, several bocks to the southeast.

The High Street IND stop on the IND 8th Avenue Line (A) is actually on Cadman Plaza East and is a reminder that High Street used to extend this far, but no longer.

The only extant piece of High Street remaining (that is still called High Street) runs between Pearl and Jay Streets. Across the intersection with Jay is the reactivated pedestrian entrance to the Manhattan Bridge walkway. A couple of trolley rails are poking up through the asphalt — this was the turnaround point for several old trolley routes including the #21 (De Kalb Avenue) and #57 (Flushing Avenue).

Howard Alley

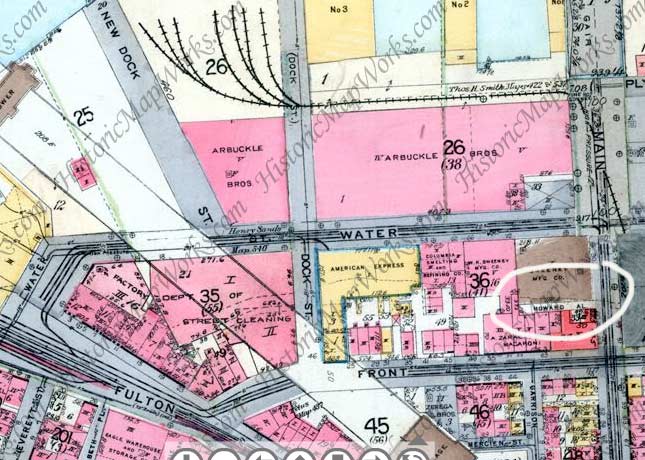

Wandering north into DUMBO, the next alley on the list is Howard Alley (circled in white on this 1916 map) issuing west from Main Street between Front and Water. Just south, the former Garrison and Mercein Streets have long been buried under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

Howard Alley is bordered on the north by The Sweeney Building, one of many lofts and factories cardboard box and corrugated paper king Robert Gair built in DUMBO beginning in the late 1880s; the Gair name can be found all over the stolid concrete and brick buildings in the neighborhood. A new building anchored by Miso Sushi sits on the alley’s south side.

Chronology of the Gair buildings is complicated by vague descriptions, additions to existing structures and an erratic numbering system. But it appears that the final effort is now known as the Clocktower Building, at 1 Main Street, between Water and Plymouth Streets, built in 1914 and called at the time Building No. 7.

Because of their near-white cast, great bulk and simple, utilitarian detailing, Gair’s buildings form an obvious interconnected network, made even clearer by the repeated appearance of his name — the most elegant of which is on two incised plaques that read ”Gair Bvilding No. 6” at the northwest corner of Washington and Front Streets, built in the 1910’s. Much of the original rail system laid in the streets still survives, and most of the old railway openings into the buildings are clearly visible.

Gair’s building on the east side of Washington, from Front to Water, has two large circles high up. One was a clock, and the other was an indicator for the wind direction: the letters N, E and S are barely apparent. Except for those circles, and the ornate clock tower at 1 Main Street, the concrete Gair buildings are severe in style, usually with neo-Classic touches, sometimes with a hint of Art Nouveau. Christopher Gray, New York Times

Belgian block and stone pavings line Howard Alley, which the city used to mark with a street sign, but is going incognito these days. Earlier maps (from the 1890s) show the alley as Howard’s Alley (a more nondescript alley closed off by a fence on York Street retains the “S” as Fleets Alley).

Dock Street

There are no more docks on this part of the Brooklyn waterfront, but Dock Street, which runs for one block between Front and Water Streets in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge, recalls a time when there were. The street has no separate addresses to call its own, and is still paved with the Belgian blocks it has had for over a century.

The Brooklyn waterfront, and the Manhattan waterfront across the river, both feature a Fulton, Water, Front and John Street. I do not know if it’s a mere coincidence.

New Dock Street

New Dock Street is a dead end running from Water Street north to the East River — likely laid out after its cousin Dock Street. It has been a primary access point for the Empire-Fulton Ferry East River State Park at the water’s edge; in 2010 the park was closed for rehabilitation. The Brooklyn waterfront, an afterthought for many years after the end of carfloating, is undergoing a revival with the ongoing construction of Brooklyn Bridge Park, which will eventually run west of Furman Street along the waterfront northeast, joining with Empire-Fulton Ferry Park. New Dock Street borders the shell of a tobacco inspection warehouse (above right).

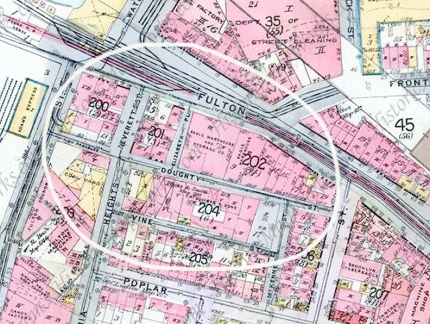

In 1916 the end of Fulton Street played host to a ferry that left river-crossers at Manhattan’s Fulton Street — the ferry had run for over a hundred years, finally ceasing operations in 1924. The end of Fulton is also host to a maze of narrow streets and short lanes that mark the intersection of the Brooklyn Heights area, to the south, and DUMBO, to the north.

Everit Street

Everit Street, formerly misspelled Everett Street on maps, runs one block between Doughty Street and Columbia Heights and Fulton Street. Here, I’m showing the only two buildings with an address on the street; one stilll has a hoist and pulley, apparently a warehouse of some kind at one time. It was named for a family of butchers who resided in the area in the 19th Century. A slaughterhouse once occupied the spot where the classic cars are parked.

ForgottenFan Brian Deck: The car flanked by the older Mercedes and the 1957 Chevrolet is a 1955 Packard Patrician sedan, Packard’s top of the line sedan that year. It wasn’t, however their top of the line car. That was the Caribbean convertible.

Doughty Street

Doughty Street is the narrowest street in the area, running from Furman east to Hicks at the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. It was named for lawyer and abolitionist Charles Doughty (1759-1844). He was responsible for the first manumission, or “slave-freeing” in 1797, and was helpful in drafting the law that outlawed slavery in NY State in 1827. African Americans for many years held a procession to his home in which they would gift him with foodstuffs and grocery goods. Brooklyn By Name, Leonard Benardo/Jennifer Weiss

According to legend, the Eagle Warehouse, designed by Frank Freeman and completed in 1893, retained part of the building at Doughty Street and Elizabeth Place where Walt Whitman edited the Brooklyn Eagle in the 1840s.

Elizabeth Place

Elizabeth Place, which like Dock Street is completely Belgian blocked and has no addresses at all, was named for Elizabeth Cornell, of a prominent family in the colonial era. Running from Doughty north to Old Fulton Street, it faces the popular Grimaldi’s Pizza restaurant on Old Fulton.

Where Doughty (left) meets Hicks Street at the BQE, it meets the remnant of the former McKenny Street (see 1916 map above), which these days is marked by a Hicks Street sign. The BQE arrived in the mid-1950s, forever changing the quality of the surrounding neighborhood. NYC highway czar Robert Moses was prevailed upon to place it under the Esplanade (or Promenade) thereby sparing the Heights from being eviscerated, but what would become DUMBO was not so lucky.

The Watchtower Bible and Tract Society (the Jehovah’s Witnesses) own several large properties where Brooklyn Heights meets DUMBO, including several large light brown stone buildings at Columbia Heights and Vine Streets. The Society also owns the magnificent Bossert Hotel in Brooklyn Heights (the interior lobby is shown on this page). The Society has been a presence in Brooklyn since 1909, and while it purchased property in upstate Ramapo, NY, there is no imminent move planned. No doubt developers would covet these buildings for residential conversion. The Bossert has been up for sale since the fall of 2009 (at this writing it is June 2010.)

Checking the 1916 map above, Vine Street formerly extended from Columbia Heights to McKenny Street, the eastern end became Hicks Street when it was rerouted during the BQE construction. The patch of green between Vine St. and the BQE has become a dog run.

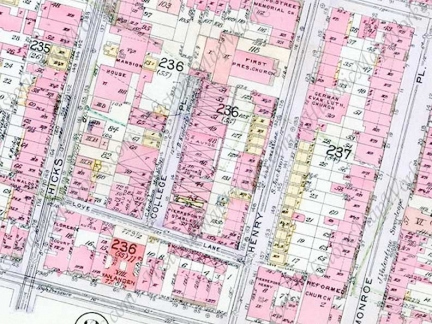

Love Lane and College Place

Not often in Brooklyn do alleys give rise to other alleys, but that occurrence is right in the middle of Brooklyn Heights, where Love Lane (left two photos) runs from Hicks east to just beyond Henry, north of Pierrepont Street. The street was named for Sarah DeBevoise, an adopted daughter of two unmarried brothers of a colonial-era landowning family, who attracted a number of young suitors. “Love lines” in the parlance of the time, were the initials etched by Sarah and her boyfriends on the fence in front of the De Bevoise home.

College Place is named for the nearby Brooklyn Collegiate Institute for Young Ladies, which was active from 1829-1842. It was run by father and son principals Isaac and Jacob Van Doren. Like other short lanes in Brooklyn Heights, Grace Court Alley and Hunts Lane, College Place is lined with small stables that have been converted to residences. One of them recently sold for over $2M.

Pierrepont Place and Montague Terrace

Both Pierrepont and Montague Street end near the Promenade at one-block streets called Pierrepont Place and Montague Terrace. 2 and 3 Pierrepont Place are said to have been built by famed 19th Century architect Richard Upjohn. Hezekiah Beers Pierrepont (1768-1838) was one of Brooklyn Heights’ early developers after his purchase of a farm from the Benson family in 1804. Hezekiah’s grandfather, Rev. James Pierrepont, founded Yale College in New Haven, CT. Hezekiah’s son Henry helped found the Long Island (now Brooklyn) Historical Society and Green-Wood Cemetery.

The Breukelen Apartments Pierrepont Place, with an entrance on Montague Street. It is a handsome Moderne building that would likely not have been built after Brooklyn Heights became a landmarked district. “Breukelen” is the Dutch spelling of the borough name.

A 1960s pop art public telephoneis still in place at Montague Street and Montague Terrace.

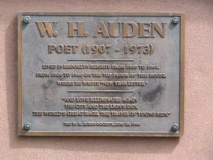

Esteemed British 20th century poet Wystan Hugh Auden (1907-1973) lived at One Montague Terrace in Brooklyn Heights for a brief time circa 1939-1940. He began the poem “New Year Letter” at this address. In 1940, he moved to the now-demolished 7 Middagh Street, joining writer Carson McCullers, composer Benjamin Britten, and dancer/author Gypsy Rose Lee. As Auden became a devout Anglican at about the time he lived here, the angels over the door seem appropriate. He also resided on St. Marks Place in the East Village.

The Double Man: Why W. H Auden is an indispensable poet of our time, Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker, 9/23/02

Montague Street is named for another writer, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762), who assisted in the institution of anti-smallpox inoculation in England after witnessing it in Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey, where her ambassador husband, EDward Wortley, was based. She had suffered from smallpox in her youth.

A tablet at the Montague Terrace entrance to the Promenade features a tablet marking the location of a house occupied by George Washington as headquarters during the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776.

6/6/10