EVEN though ancient subway car tours are kind of pricey at $20-$25 a trip (for Transit Museum members) I try to make at least a couple of tours a year. The Transit Museum trots out a set of cars from the 1910s, 20s, 30s, 40s or 50s, and runs them on an unusual route (one year we went to Canarsie via the Broadway Line (this used to be the BMT KK route; it was discontinued during the Nixon administration).

July 2005 found us riding in a set of Low Voltage (Low V) cars from the Grand Central shuttle platform to Van Cortlandt Park. To make that connection, the train has to use the shuttle platform’s connection with he Lexington Avenue line (a non-revenue route), roll down to the loop past Brooklyn Bridge then up to the Bronx, and make a switch to the #2 line just past the 149th Street station, swing south to 96th Street, reverse and run up Broadway to the end of the #1 line at 242nd Street.

This route took us past the four major abandoned stations in the New York City subway system. Unfortunately we rolled past three of them way too fast to register anything interesting but fortunately, the train crew slowed us down as we passed the most magnificent of them, the City Hall station, the one where the subway system got its start on October 27, 1904.

Above three photos: Dane Kolomatsky

When the NYC subway ran for the first time on October 27, 1904, it ran from the City Hall Station, once the flagship station of the system. It was designed by George Heins and Christopher LaFarge, who also designed every other NYC subway station opened between 1904 and 1908. The station is unique in its use of colored tile and terra cotta used nowhere else in the system, has unique skylights, ceiling lighting and Guastavino tiling.

The station later proved impractical for lengthier trains. The steep curve of the platform made for too much of a gap when doors opened. Thus the station was closed in 1945 and has been all but abandoned since. The skylights were cleaned for the Centennial celebration in 2004 but everything else has ben left as it was witth the exception of the wooden ticket booth, which has long since been removed. The station has been discussed as an adjunct of the NYC Transit Museum in downtown Brooklyn, but the station’s location directly under City Hall in the Age of Terror makes any permanent reopening unlikely.

Saul Blumenthal’s City Hall station page

nycsubway.org City Hall station page (including recent views from the Centennial celebration)

Joe Brennan’s City Hall station page

Additional images of City Hall station can be seen from my subway postcards page, and I have more coming when I do my original 1904 subway stations page, coming soon to a computer near you.

We also sped past the old Worth Street station, which is just to the north of the Brooklyn Bridge station, first stop on the Lexington local (#6). Just enough time to catch some of the graffiti, the “Worth” sign on the pillars, and if you look closely on the upper right of the last picture, one of the terra cotta “W” friezes that are still in place. You can find similar ones at Spring and Bleecker Street.

Worth Street was closed in 1962, when Brooklyn Bridge station was expanded north, making it superfluous. This means that the Brooklyn Bridge station is surrounded by two abandoned ones, City Hall and Worth Street.

The street was named for Mexican War hero General William Worth.

Joe Brennan’s Worth Street page

We also whizzed past the 18th Street (Lexington IRT line) and 91st Street (7th Ave-Broadway IRT line) stations, way too fast to get anything good.

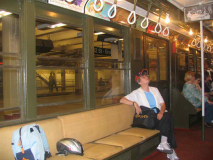

ON BOARD

Low V, or low-voltage cars, were in use in both the IRT and BRT (Brooklyn Rapid Transit) from 1915 to the early 1960s. They were constructed between 1915 and 1926 by Pressed Steel Company, Pullman, and American Car and Foundry. The cars in use on this Transit Museum trip were #5290 and 5292, built in 1917 by Pullman, and #5443 and 5483, built in 1924 by ACF.

Low voltage cars’ master controllers ran on 32-40 volt direct current battery to operate 600 volt direct current group switches under the cars. This enabled the cars to be run more safely since traincrew members didn’t have to chance contact with 600 volts of direct current.

Above: Grand Central shuttle platform.

The Shuttle from Times Square to Grand Central was once a part of the subway main branch, which began at City Hall, up Elm (now Lafayette) Street, 4th, Park and Lexington Avenues, west under 42nd Street, then north along 7th Avenue and Broadway to 145th Street. Expansion of this original trunk north and south came immediately (new stations appeared two months after the subway opened), and by 1918 the stretch along 42nd Street had been converted into an awkward shuttle arrangement between the East and West Side IRT trunk lines. The shuttle arrangement has been improved over the years, though a crude metal platform blocks the shuttle trains access to the west side line (it can be removed when need be).

West 242nd Street-Van Cortlandt Park. The weather was in the upper 80s, with comparable humidity, and on our trip uptown the cars were surprisingly cool with the aid of ceiling fans and open windows. After a 3-hour layover in the yards in the sun, however, the cars were warm indeed on our return voyage.

The design shown here dominated subway car design for the early part of the 20th Century. Other cars on the BMT routes were able to place (quite small!) seats in ones and twos looking out windows, notably on the Triplexes that soon followed these models, but these cars used the bench system that is used today.

The overall effect is much closer to actual railroading instead of mass transit, as incandescent lighting, porcelain posts and handrests, and softer woven seats made for a more comfortable riding experience. However, rush hour on trains that had been in the sun for awhile was undoubtedly sometimes brutal.

Luna Park, named for a simulated trip to the moon exhibit based in part on H.G. Wells‘ novel First Men In the Moon, was a dazzling Coney Island attraction for decades beginning in 1903, with its 250,000 illuminated electric lights in the early days of that innovation. (Other accounts have it that the park was named for a sister of one of the original partners, Luna Dundy.) The park burned in an August 1944 fire and again, after reconstruction had started, in October 1946. The name is remembered by Luna Park Houses, which stand where the grand amusement park once did above Surf Avenue between Stillwell Avenue and West 8th Streets.

The elephant in the ad is either meant as a historical reference or is rather crassly exploitative, since Topsy the Elephant was killed at Luna Park in a test of electrical systems between Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse in January 1903, a few months before the park’s official opening in May. Luna Park adopted elephants as an unofficial symbol.

Not a crude epithet. The product takes its name from classic mythology; Hebe, the goddess of youth, was the cup bearer at Olympus and married Heracles, or Hercules, as the Romans called him. Since the myths were commonly taught in school back then the majority of riders were probably able to make this inference.

We’ll reference Massachusetts General Josiah Porter (1830–1894) here: he was the first Harvard grad to enlist in the Union Army during the Civil War and attained the rank of captain in 1861. He became a major general in 1886.

Van Cortlandt’s Tail, a short strip of park at Broadway and Van Cortlandt Park South, is host to an annual Christmas tree lighting. It was probably named as a whimsical Henry Stern-ism.

Your webmster’s companions on this Transit Museum voyage were occasional mermaid Gerry Guadagno and son Dane Kolomatsky.

Page photographed July 10, 2005 and written July 17.