EDGED as it is between the Russian delis and nightclubs of Brighton Beach, the colonial houses and cemeteries of Gravesend, and the sideshow freaks, kiddie rides and mermaids of Coney Island, West Brighton doesn’t get a whole lot of attention. Yet the small area dominated by the Warbasse and Trump Houses has its own collection of relics (besides your webmaster, who toured it in the late summer of 2005).

The main street to West Brighton from the north is Shell Road, which today extends from the junction of Avenue X, McDonald Avenue and 86th Street (one of NYC’s rare intersections where three streets change names) south to Neptune Avenue and West 8th Street. Shell Road first appears in 1829, when the Coney Island Road and Bridge Company built a toll road spanning the strait separating mainland Gravesend from Coney Island, which was actually an island in that era. The road led to the first Kings County seaside resort, Coney Island House; it may have been paved with oyster shells. Luminaries like Washington Irving and Walt Whitman stayed at the resort.

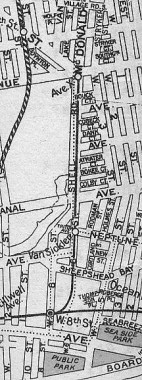

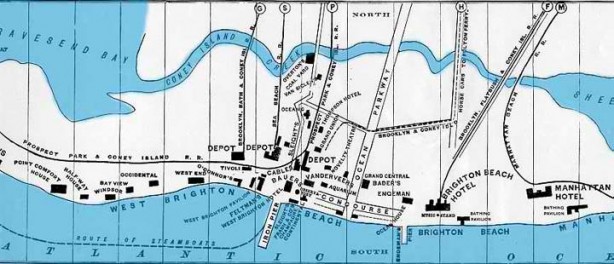

Shell Road/West Brighton map, 1938 (Ah, that’s Canal Avenue, not Anal Avenue.)

Shell Road/West Brighton map, 1938 (Ah, that’s Canal Avenue, not Anal Avenue.)

In the late 1800s Coney Island Creek was turned into a channel connecting Sheepshead Bay and the Narrows, but by the early to mid 1900s it had been filled in for the most part and Coney was no longer an Island. Railroads such as the New York and Manhattan Beach (built by Austin Corbin), Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island (the West End Line, since it was westernmost of all the railroads; there was also a hotel called the West End), the Sea Beach (leading to the Sea Beach Hotel), the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island (the Brighton Line) and the Prospect Park and Coney Island (the Culver, for its originator Andrew Culver) had been built in West Brighton, Coney Island and Brighton Beach to bring customers to the many extravagant seaside resorts and hotels that rose in the late 1800s.

This map (which accompanies Jeffrey Stanton’s online article on Coney Island transportation) shows all the major railroad lines arriving at the Atlantic Ocean in Kings County in 1879, when the resort scene was at its zenith. Note that there were very few roads there in this period: you arrived in Coney Island by train or boat. Ocean Parkway and coney Island Avenue were built in the 1850s and would eventually begin a spate of street and road building. Shell Road here is shown by the thin line crossing Coney Island Creek just west of the Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad. The PP&CIR, built by Andrew Culver, would eventually evolve into today’s BMT F train, which even today is known as the Culver Line. The thin line proceeding east from Shell Road would become Neptune Avenue.

This map (which accompanies Jeffrey Stanton’s online article on Coney Island transportation) shows all the major railroad lines arriving at the Atlantic Ocean in Kings County in 1879, when the resort scene was at its zenith. Note that there were very few roads there in this period: you arrived in Coney Island by train or boat. Ocean Parkway and coney Island Avenue were built in the 1850s and would eventually begin a spate of street and road building. Shell Road here is shown by the thin line crossing Coney Island Creek just west of the Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad. The PP&CIR, built by Andrew Culver, would eventually evolve into today’s BMT F train, which even today is known as the Culver Line. The thin line proceeding east from Shell Road would become Neptune Avenue.

A Walk on Shell Road

As we’ve said 86th Street (left) starts here, at the north end of Shell Road. It runs in a nearly straight line NW all the way to Shore Road in Bay Ridge; it is mostly residential, except for a stretch where it serves as the main shopping street in Bensonhurst under the old West End Line, today’s D train (though the letter is changed every few years). A second commercial stretch appears in Bay Ridge.

As we’ve said 86th Street (left) starts here, at the north end of Shell Road. It runs in a nearly straight line NW all the way to Shore Road in Bay Ridge; it is mostly residential, except for a stretch where it serves as the main shopping street in Bensonhurst under the old West End Line, today’s D train (though the letter is changed every few years). A second commercial stretch appears in Bay Ridge.

Gravesend Avenue, renamed McDonald Avenue in the 1920s, has always served as a transportation line; the Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island railroad ran along it at grade, until it was purchased by Brooklyn Rapid Transit and elevated in 1917-1919, taking over the Culver Line. Below the junction of 86th Street and Avenue X, McDonald Avenue becomes Shell Road.

Follow along with a Google Map of Shell Road and West Brighton

Railroad pioneer

From Shell Road’s junction with 86th Street and Avenue X, walk down X to the west for about half a block. You’ll see a tree-lined street called Boynton Place.

Hidden histories abound in New York City’s street names. Boynton Place connects West 7th Street and Avenue X between 86th Street and the MTA’s Coney Island Subway Yards. Its location at the trainyards is not serendipitous.

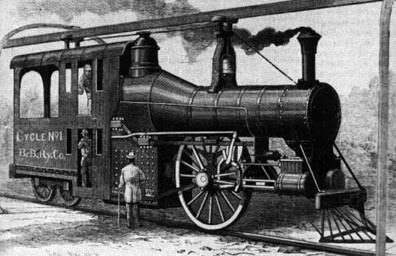

Loco on Boynton’s “bicycle railway” in 1888

Loco on Boynton’s “bicycle railway” in 1888

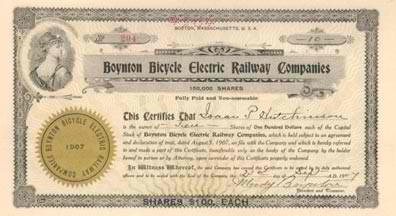

$100 stock certificate for Boynton Bicycle Electric Railway. (image from scripophily.com)

$100 stock certificate for Boynton Bicycle Electric Railway. (image from scripophily.com)

Eben Moody Boynton was an entrepreneur and inventor in the 1880s and 1890s. Though railroads had already been in common use for nearly 60 years at that time, experiments with their efficiency were still ongoing. It was Boynton’s idea to reduce the loads carried by traditional tracks laid on the ground by placing one track on the ground and another track overhead, resembling a monorail but with two tracks instead of one. Boynton claimed such an arrangement would enable trains to run at the unheard-of speed of 60 miles per hour. An experimental locomotive and trainset, as well as tracks, were constructed in the Coney Island grasslands. Critics dubbed Boynton’s creation the “Flying Billboard” since the loco and passenger cars were only 4 feet wide. His train did exceed 60MPH, but he was never able to obtain enough backing to expand. Rails from the experimental railroad later replaced those on the nearby Sea Beach line (today’s N train).The inventor is remembered by Boynton Place, which reportedly is in the train’s old right-of-way.

Coney Island Yards

Vast Coney Island Yards, the premier transportatioin repair facility in New York City, fronts along Shell Road between Avenue X and Avenue Z. It opened in 1926 and provides repair and rehabilitation for 5800 subway cars plus cars used on Staten Island Railway.

NYCSubway.org features hundreds of pictures of Coney Island Yards

The main entrance of Coney Island Yards features a chalet-like entrance apparently built along IND specs (the door design in general is close to that of the West 181st Street station on Ft. Washington Avenue in upper Manhattan on the IND). This is unusual since the Coney Yards serve BMT trains. It’s the same building that was built when the yards opened in 1926 so perhaps the same design that was then current when the IND was being built that year was used.

Two stylized lampposts flank the main entrance. My theory is that these are an unused design for IND platform lamps. (The IND doesn’t employ platform lamps; only two IND stations, 4th Avenue and Smith-9th Street, are elevated and neither station uses such lamps.)

The MTA’s Steeplecab #7 is visible from Shell Road.

The MTA’s Steeplecab #7 is visible from Shell Road.

Steeplecabs were electric freight switching locomotives. Both mainline and interurban and urban electric rapid transit systems used them. They are called steeplecabs because they had angled ends for good visability from the center cab and a platform at each end for a brakeman to stand on when performing switching duties, so the cab rises over the rest of the car like a steeple. The cars had a trolley pole or a pantograph and/or third rail shoes for electric pick-up. Coney’s steeplecabs are museum pieces no longer in active service.

On Coney Island Yard’s identification shield we find two local landmarks, Deno’s Wonder Wheel (1920) and the Parachute Jump (moved to Coney in 1940).

On Coney Island Yard’s identification shield we find two local landmarks, Deno’s Wonder Wheel (1920) and the Parachute Jump (moved to Coney in 1940).

Shell Lanes

The eastern side of Shell Road is dotted with short streets with unusual names: Bouck, Cobeck, Dank, Atwater, Bokee and Colby Courts. These are probably the names of now-forgotten developers. At Bouck Court and Shell Road we find one of New York City’s disappearing species…

I did most of my bowling at Leemark Lanes on 88th Street in Bay Ridge, though I belonged to leagues that bowled at Bowlmor near Union Square, Mark Roth‘s now-deceased Rainbow Lanes in Sheepshead Bay, and alleys on Snyder Avenue in Flatbush whose name escapes me. I have only bowled once at Shell Lanes. Your webmaster could never get better than a 150 average: couldn’t throw a hook.

Now that bowling seems destined to become a niche sport (or more of one than it ever was) all lanes should all be required to maintain their 1950s-era decor, like Shell Lanes has, at least outside.

Shell Road rolls on past housing projects and used car lots; no one living and working in the area knows they’re on a road that’s over 175 years old.

The road less traveled

The Belt (originally Circumferential) Parkway was built in 1939-1940, and since the Culver El had been here since 1919, it had to be raised over the parkway.

West 6th was a wonderland for your eleven-year old webmaster when he encountered it on a bicycle in 1968 at age 11. Shell Road jogs to the right before ending at Neptune Avenue (check the above map for confirmation) and West 6th Street takes over its route south of the Belt Parkway. In ’68 the city had not yet gotten around to modernizing its lamppost stock here, so to my gaping wonder were all manner of old castiron telephone pole masts on which were mounted gumball and cuplight incandescent fixtures; various old luminaires were similarly mounted under the el.

“New cuplight” design at el at West 5th near Surf. This new design seems to be a recapitulation of the older incandescent “cuplight” design, which can still be seen under other overpasses around town.

“New cuplight” design at el at West 5th near Surf. This new design seems to be a recapitulation of the older incandescent “cuplight” design, which can still be seen under other overpasses around town.

Relics persist here. At the V formed by Shell Road and West 6th you can still see old trolley tracks, a remnant of the line that ran down McDonald Avenue and Shell Road. The tracks curved east for a block to their terminal at West 5th.

In this in-between corner of Brooklyn, even the name of the local elevated station was a decades-old anachronism and caused a fair bit of confusion. Until the 1990s the station on West 6th north of Neptune Avenue was known as Van Siclen, even though Van Sicklen Street, in Gravesend, and Van Siclen Avenue, in East New York, are nowhere nearby. The answer to the conundrum is that this elevated station on the Culver originally was a stop on the Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad serving the Van Siclen Hotel (see map above.). The at-grade station was subsequently elevated and changed management and ownership, but the name persisted for a good 80 years after the hotel was torn down! It is now the Neptune Avenue station, even though it’s a block away from that street.

Ah, but the Van Siclen stop did occur at a crossing avenue that wasn’t Neptune Avenue. And thereby hangs a tail, or rather, the tail of a merman… (Above images from nycsubway.org)

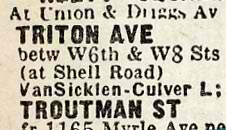

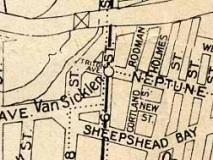

Before the Peter Warbasse Houses were completed east of West 6th and south of the Belt Parkway in 1964, the area was full of little streets like Rodman, Holmes, Cortland, Dewey Place (not on the map) and Triton Avenue, a former important trolley turnaround. Cars would turn left onto Neptune Avenue, which Triton became after crossing West 6th, and follow it into a terminal. The trolley era was over by the 1950s, the construction of Warbasse Houses in ’63-’64 wiped out all these small streets, and Neptune Avenue was thereafter straightened. Triton Avenue, though, named for the fish-tailed, conch-blowing son of Poseidon (Roman name: Neptune), god of the sea, was not eliminated so easily. In fact, Triton has left his scales all over the area.

Cuts in the sidewalk at the Neptune Avenue station on West 6th (above) formerly belonged to Triton Avenue. A path through the parking lot at Brightwater Towers approximates Triton Avenue’s old path, though the actual street was a bit north of it.

Still not enough evidence for you?

Two old metal/porcelain signs hang on a lamppost on Shell Road’s west side, in front the road’s only private dwelling, at Triton Avenue’s former intersection.

Some detective work and a bit of speculation is in order here. These cylindrical-shafted lampposts date to the late 1970s and early 1980s; the DOT switched to them temporarily, instead of the usual octagonally-shafted design. Triton Avenue was eliminated around 1968, when I saw it being cordoned off and paved over. It’s likely that the DOT guys were under orders to move all signs they found on the old poles being torn down onto the new, and they followed these instructions to the letter, repacing leftover signs for a street that had been eliminated a full decade earlier.

West Brighton

Shell Road ends at Neptune Avenue and West 8th Street, leaving us in West Brighton. There’s plenty here to keep us busy. Meander through the public paths of the projects to West 5th Street and Seabreeze Avenue, where we find…

…the abandoned West Brighton Little League field, with Trump Village looming behind, over the el. Fred Trump(1905-1999), from Woodhaven, Queens, became wealthy by developing reasonably-priced housing in Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island.

Across the street from the abandoned field we find Asser Levy (Seaside) Park, named for the first Jewish citizen of New Netherland: Levy, leading 23 other Jews, emigrated here from Brazil in 1654. He became the first Jew to serve in a militia and own property, the first kosher butcher in the New World, and a founding member of Shearith Israel, the country’s first Jewish congregation. This park, as well as a recreation center and block-long street at East 23rd near the FDR Drive in Manhattan are named in his honor.

Of course a prime attraction is the presence of a 1960s-era Westinghouse luminaire; these, lacking a glass diffuser, were used primarily on side streets and in parks. It’s mounted on a 1963-vintage Deskey pole.

Asser Levy Park’s most striking component is the Sidney Jonas Bandshell: Jonas (1905-), a labor union organizer, is a founding member and chairman of the Brighton division of the Brooklyn Arts and Culture Association and was instrumental in planning and building the bandshell, which has played host to Liza Minnelli, Patti LaBelle and Michael Bolton in its summer concert series.

SOURCE:

How We Got To Coney Island, Brian Cudahy, Fordham University Press 2002

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

This page was photographed in August 2005 and completed September 25, 2005.

Why don’t you get one?

FORGOTTEN NY T-SHIRTS AND MORE

erpietri”@”earthlink.net

©2005 Midnight Fish