[Beginning in 2009, Queens Plaza, which runs along the Queensboro Bridge ramp to Queens Boulevard crossing the Sunnyside RR Yards, was given a complete renovation that wiped away most of what is shown on this FNY page that was written in 2007. Pedestrian plazas, bike lanes, and a brand new plaza at Northern Boulevard were added. A cluster of peep shops and fast food joints were removed, as well as what was the world’s ugliest parking garage in a world full of ugly parking garages. Here’s what we lost. I don’t miss a thing.]

If you’d like to know why Queens is made fun of and occasionally condescended to by our Manhattan cousins, look no further than Queens Plaza: the gateway to Queens, the first thing many motorists see when arriving via the Queensboro Bridge (known by Manhattanites as the 59th Street Bridge), and the first stop on the BMT from Manhattan.

Screeching elevated trains serving two lines roar overhead at all hours; strip clubs abut fried chicken joints and donut shops; Rikers Island drops off ex-cons here, and prostitutes and gangs roam freely; The Queensboro Plaza el station, despite a renovation a cople of years ago, is bone-chilling in winter and a dripping, leaky mess on its second level (to say nothing about frequent service outages on the #7).

And, of course, Queens Plaza boasts the ugliest building in Queens, and possibly all of New York City. Let’s take a look at this much maligned nexus, and, if we can, glean a glimmer of hope for it to regain some semblance of respectability.

To begin let’s turn the clock back to 1912…

Jeff Vandam, New York Times:

Until 1909, Queens had no plaza to speak of. That was the year the arched steel spine of the Queensboro Bridge was completed, 11 years after Queens officially became part of the City of New York, a moment when the population of Manhattan was poised to burst into the relatively untouched borough to the east. The bridge and the plaza that was created to accompany it on the Queens side were a sight to behold, and arrived with appropriate fanfare.

When work on the bridge was finished, 50,000 people gathered to celebrate its opening, according to Vincent Seyfried’s book “300 Years of Long Island City.” The mayor, the governor and the secretary of war made speeches, a parade passed through the new plaza, and thousands of red lamps glowed from the bridge’s cables. The ceremony culminated in a fireworks display, designed to resemble Niagara Falls, which poured over the side of the bridge.

To accommodate all the people who would pour in from Manhattan, a byway called Jane Street was widened by 90 feet to become Bridge Plaza North and South (today’s Queens Plaza North and South). Dividing the inbound and outbound traffic lanes was a series of grass-covered squares, separated by cross streets. Inside each square, landscapers used flowers and shrubs to create horticultural sculptures, including a 75-foot crescent with a Japanese cherry tree at its center.

Photographs of the plaza taken in the weeks before it opened show a startlingly spacious and uncluttered setting. Few buildings lined the plaza, and a flagpole at its center, made from the mast of Shamrock, the yacht of Sir Thomas Lipton of tea fame, stood in proud isolation. Queens Plaza at its inception was nothing less than a dignified, serene portal of a great city.

Almost immediately, however, the plaza began falling victim to its success. The bridge, designed to accommodate multiple lanes of horse-drawn buggies, automobiles, bicycles and pedestrians, could not possibly accommodate all who wanted to travel between Queens and Manhattan. By 1915, a great tangle of elevated subway tracks had been strung over the heart of the plaza, producing one of the most complex overhead interchanges of all time and bringing ear-splitting noise to those below.

![]() additional 1912/2006 Queens Plaza pix at Bridge and Tunnel Club

additional 1912/2006 Queens Plaza pix at Bridge and Tunnel Club

Queens Plaza South and 27th Street, December 2006. The tangle of elevated tracks –deemed “Queensboro” Plaza, as its builders named it — constructed in 1914-15 soon after the bridge opened, doomed the serene plaza pictured above, as the underground BMT, now the N and W train, elevated soon after entering Queens via an underground tunnel, and the Flushing Line, at first a joint operation of the BMT and IRT, entered via tunnels originally built for streetcars by piano magnate William Steinway.

Jackson Avenue and Queens Boulevard

It’s hard to conceive of it now, but the el tangle of Queens Plaza used to be double its present size. Until 1942 a third elevated line entered the plaza, this one an extension of the Second Avenue Elevated via the Queensboro, and there were two more trackways and another platform at the north end of the station. When the IRT-BMT situation was simplified, with the IRT going to Flushing and the BMT to Astoria, the entire north end of the station was razed. Little trace remains of the old tracks and platforms, but there are “fancier” windows and railings on the south side of the viaduct that were the originals.

Does one of those packages on the ad say “cock”? Why, yes, it does.

Vandam: In the late 1950’s and the 1960’s, urban decay began eating away at many corners of New York, including once-vibrant business districts that saw their tenants flee for the suburbs. Queens Plaza was no exception. By the 1970’s and 80’s, the streets had been taken over by trash, broken glass, drugs and pimps. Newly freed inmates from Rikers Island began disembarking daily in the plaza, courtesy of an early-morning bus that deposited them there from the jails.

Prostitution spread through the neighborhood, to the point that women employed by local businesses complained of being followed around by men when they left work at the end of the day. The Q-Plaza Motel, at Vernon Boulevard and Queens Plaza South, became notorious as a hot-sheets establishment.

In 1975, the Queens Plaza Municipal Parking Garage was built at 28-10 Bridge Plaza South and Jackson Avenue.

An architectural firm called Rouse, Dubin and Ventura designed what Vandam called “a brown concrete structure resembling a 1970’s filmmaker’s idea of an intergalactic battle station.” The brown object at the corner just below the roof was supposed to resemble a simulated rock outcropping; instead, it looks like, well, an actual piece of…

The building is clad in striated beige concrete. Someone has, sometime in the past, stenciled “Welcome to Queens Plaza” on the plaza’s south side. The businesses on the ground floor have all become shuttered, in anticipation for the building’s hoped-for (by your webmaster) demise. This is one case in which preservation is definitely off limits. Rumor has it that developer Tishman-Speyer, owners of the Chrysler Building and Rockefeller Center, are ready to raze it and construct a huge office tower here. Your webmaster, who usually opposes big bad developers, says you can’t remove this Fedders-era thing soon enough.

In the past, an enterprising artist has gamely attempted to enliven the garage by placing potted art on the Queens Plaza South and Jackson Avenue sides. For the most part the intention is greater than the art, but hits the mark on two occasions…

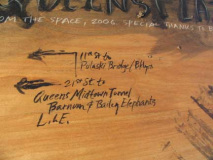

first, with a wood map of the Queens Plaza area…

…and then there’s Ghidrah, the three-headed public pay phone!

It took a “summit meeting of monsters” to save the Earth in 1964, and it just might take something similar to save Queens Plaza in 2007.

U.S. Rep. Carolyn Maloney announced in 2006 that funding had been found to rebuild the Queens Plaza roadway, making it safer for motorists and pedestrians. My money’s still on Godzilla, Rodan and Mothra to save the day.

You’ve seen and heard about Queens Plaza’s decrepitude, but there’s a hidden history here too…especially on a tiny traffic island on the northeast end of the plaza…where two of Queens’ longest streets, Northern and Queens Boulevards, have their source…

Long before Citi Tower was finished in 1989, the Queens Plaza area had its own skyscraper…the 15-story Bank of Manhattan building, finished in 1927…something Howard Roark himself may have conceived of. That year, American architecture was shedding Beaux Arts and adopting the more streamlined techniques of the Machine Age. That didn’t stop the Bank’s architects from adding all kinds of Easter eggs way up high, like the 4-sided clock, the water bearer, fish and shell.

Long Island Star- Journal, October 1925: The Bank of Manhattan’s new building for Queens Plaza will set the pace for the Long Island City skyline. The building will tower far over the present buildings. The projection is that Bridge Plaza will be the new Times Square of Queens. The 14 story building is to be graced with a four faced clock. The Plaza is expected to become the business and financial center of Queens. Transit facilities give it access to the South Shore as well North Shore. Greater Astoria Historical Society

Non-Rolling Stones

Walk over to the concrete triangle at Queens Plaza North and 41st Avenue, right in front of the bank tower. There’s a lone tree, pigeons, a no-parking sign, and two of the oldest man-made objects in New York City since colonization began.

In 1650, Dutchman Burger Jorissen constructed a grist mill that today would be on Northern Boulevard between 40th Road and 41st Avenue. The mill existed on the site for about 211 years, until 1861 when it was razed by the Long Island Rail Road. The Payntar family by that time owned the mill property (40th Avenue was called Payntar Avenue until the 1920s) and had placed millstones that had been shipped in by Jorissen around 1657 in front of their house. When Sunnyside Yards, Queens Plaza and the elevated were constructed, the millstones were fortunately preserved and embedded in the traffic plaza, where nearly no one notices them.

[when the plaza was renovated in 2011, the millstones were dug up and placed without any historic markings on the north side. Reports indicate that historic markers are in the works.]

Oh, the Murality

Look to the left of the Bank of Manhattan, across 41st Avenue, and you’ll see the smaller, Doric-columned Long Island Savings Bank. It’s noted not for what’s on the exterior, but what was inside.

The Vault nightclub’s name hints at what the building’s previous use, as well as the pair of eagle medallions.

The Long Island Savings Bank moved here to Queens Plaza in 1920. In 1939, concurrent with the opening of the World’s Fair in 1939 it commissioned Naples-born artist Vincent Aderente to depict the history of Queens in a mural 30 feet in height.

The Long Island Savings Bank moved here to Queens Plaza in 1920. In 1939, concurrent with the opening of the World’s Fair in 1939 it commissioned Naples-born artist Vincent Aderente to depict the history of Queens in a mural 30 feet in height.

Greater Astoria Historical Society: The story begins nearly 350 years ago into the time when Indian canoes plied the waters of what is now the greatest city in the world. The earliest medium of exchange was wampum. Jackson Mill, among the oldest land grants in Queens, represents the beginning of property ownership and first commercial enterprises in the area. The mural also depicts western Queens’ oldest church building, St. James Church, and its oldest house, the Lent Homestead.

Near the top of the mural, we go from yesterday to the world of tomorrow. On the right are the old factories of Long Island City. Opposite, we find contemporary loft buildings. The Queensborough Bridge passes over the East River with modern shipping in stark contrast to the Indian canoes. Against the skyline of Manhattan, an airplane wings into the future.

![]() Larger view of the mural with extra historic details

Larger view of the mural with extra historic details

GAHS: The thirty foot mural proudly graced LISB’s banking floor for decades. In the 1990s, the bank merged into Astoria Federal Savings & Loan. The building was sold with the painting still in place.

Letter-Carrier Mike Mannetta of the US Postal Service, who admired the mural while on his daily route, researched both the work and the artist. One day in May, 2000, he was horrified to find the mural missing. Workers came in over the weekend and removed it. He informed the Greater Astoria Historical Society who alerted the media and arts community. Coincidently in the Jackson Heights branch of Astoria Federal, a copy of the lost mural was found in a storeroom by employees Benjamin Caiola, and Phil Steinberg. They displayed it in the vault area.

The public, alerted by publicity surrounding the theft, notified the Greater Astoria Historical Society of the Jackson Heights copy. Astoria Federal graciously agreed to donate this copy to the Society for the benefit of our community. Thomas M. Quinn & Sons offered to display it. Nothing is known of the copy’s history.

Sadly, the building was demolished in October 2007 and nothing has yet taken its place.

Some FNY-type anomalies are here at the traffic island, too. A Cyclops traffic caution lamp is mounted on a lamppost, while some original Belgian block paving can be found on 41st Avenue. (The lines are likely from recent cable-TV excavation, not from trolley tracks.)

A long-lost liquor store ad, Jackson Avenue south of the Plaza

A short stroll along Queens Plaza North…

Take another look at the 1912 Queens Plaza pictures at the top of the page. One of the buildings is still there, minus its clock tower.

This 6-story 400,000-square footQueens Plaza North monster, the Brewster Building, built in 1911 at 27th Street, once turned out horse-drawn carriages and Rolls Royce automobiles. It has been the home of Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and was beautifully restored in recent years, though its original clock tower has been long absent. Cole Porter mentions Brewster auto bodies in his song “You’re The Top.”

Brewster & Co. got its start in 1810 as a carriage manufacturer and built its first auto in 1905. Brewster went out of business, however, in 1937, the clock tower was removed in the 1950s, and the building became somewhat rundown until its renaissance in the 1990s.

Sources:

Greater Astoria Historical Society

LIC in Context, Paul Parkhill and Katherine Grey, Furnace Press 2005

“For Joey Hot Dog, a World on the Wane.” Jeff Vandam, New York Times, July 9, 2006

2/4/2007

2 comments

Used to hang out with the ladies of the night n their pimps at the liquor store caddys with white walls n t.v.antennas on trunk lids good times …..

I lived 1 block north of Queens Plaza, at Crescent Street and 41st Avenue, with my parents and 4 siblings from 1956 to 1971. I was 6 when we moved there and 19 when we moved to Flushing. The neighborhood

was an ideal place for a kid to grow up. It was a mixture of commercial businesses and residential 1 and 2 family homes, but all the residents knew each other and looked out for each other. It was a very happy

period in my life. I still have many friends from my time in the LIC neighborhood, and we gather occasionally in the area for reunions. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world.