CONTINUED FROM PART 1: 5 For Lighting, Streetlight Themes on the Queen of Avenues

On the previous page in this series, FNY explored Fifth Avenue’s status as the great repository, and ultimately, graveyard, of some of the city’s most notable lamppost styles. Various eras have seen styles that represented the architectural styles of their time installed on the Queen of Avenues; for example, the Beaux-Arts era saw flocks of ornamented scrolled castiron Twinlamps, in two separate styles, placed on its corners from 1892 all the way to 1965. A number of different, more modern styles have replaced the Twins on Fifth, most of them esthetically unsuccessful…

Traveling north on 5th (on foot; one-way auto traffic runs south on 5th Avenue) the final representative of the old order is this Type 24M Twin on the SW corner of 5th and West 32nd Street, seen here “foredropped” against one of 5th’s newest apartment towers at 325. The tower is representative of the new trend in apartment architecture in NYC: glass fronts. Better have curtains or blinds ready!

Rise of the Robos

We now come to NYC’s most insidious, and regrettable, lamppost trend of the past two decades…

The Empire State, the King Of All Buildings, was completed in only a year and 45 days, from 1930-31, and was finished a month ahead of schedule and $5M under budget. Try that these days.

Like its predecessor the Flatiron Building, the sidewalk in front of the building is perennially covered by scaffolding, as constant work is needed to maintain the buildings’ exteriors. At least this time, they got a bit clever and signed the covering “The Empire State Rebuilding.” Your webmaster is one of the very few NYC natives to actually ride the elevator to the top and take in the view from the observation deck (in September 2000). New Yorkers are expected to be cavalier about our landmarks and looking skyward is the dreaded mark of the rube.

Unfortunately this spot on 5th marks the beginning of an on-and off- series of lamps erected in the early 1990s and onward by the otherwise-admirable 34th Street Partnership:

Founded in 1992, the 34th Street Partnership is a coalition of property-owners, tenants, and city officials, working to revitalize a 31 block district in the heart of midtown Manhattan with major streetscape improvements, special security and sanitation services, public events, tourist assistance, and free retail services. The Partnership’s programs and services are funded principally by a special assessment on commercial properties within the district. Funds are collected by the city and returned in full to the Partnership. 34thStreet.org

I call them the RoboLamps: they’re all green, most have two heads, and all shine a bright white metal halide light at night. When they first appeared in 1992 they bucked the trend of the 1970s and 80s toward yellow sodium-based streetlighting.

I should dig the Robos, I really should. For one thing, they’re modular and adaptable, attributes I laud in the Deskeys seen later on ths page. Two separate stoplight designs can be hung from them: the familiar guy-wired stoplights seen at the top left, and shorter-necked ones for less-important corners. The early 2000s saw a new trend in street signing that is used exclusively on these poles: reflective signs that shine brighter in car headlights (a pair of large specimens can also be sen in that shot).

But there’s a sameness about them that defeats me. Only one type of luminaire can be placed on them, the one shown above, which is a sort of hommage to the Westinghouse “cuplight” that appeared in the 1940s. But you never see anything different on them. My friend Jeff Saltzman, he of Streetlite Nuts, has assigned different personalities, like “Cheerful” and “Doubtful” to the different luminaires that appeared at the dawn of the green-white mercury era in the 1960s and, indeed, they do seem to present moods and hints of personalities. These lamps though, are soulless.

The Robos are adaptable enough that they can expand, like a Transformer, into an information kiosk in spots (like here, between West 34th and 35th). These are marked by large stenciled letter “i’s.”

Good thing they did this before Steve Jobs can copyright the letter “i.” I hear he’s working on it. Well, he would if it were possible to copyright a letter. After all, the word “I” is in the top five of the most popular English words, and think of how much money that would generate. English, incidentally, is one of the few languages, if not the only one, that capitalizes the personal article.

37th-39th Streets pose an interesting tableau for lamppost aficionados. At left we see the short-armed stoplight attached to the Robo’s modular unit at its apex. Center, a Deskey-type stoplight (a reminder that twin Deskeys used to occupy this part of 5th Avenue) holding two 34th Street Partnership-type blue street signs, and right, a mid-block Robo. The basket a little below the midpoint holds flowers in season.

The 34th Street Partnership has installed blue street signs in the districts it has improved, which is pretty much all of midtown from 32nd to 45th Streets and from 3rd to 8th Avenues. There have been three separate generations, the first is pictured above, with Palatino type font; the second are a little bigger and darker, and the third are the large reflective signs used at major intersections.

Rise of the Donalds

Continuing north, at the NE corner of 5th Avenue and East 40th, across fropm the Mid-Manhattan Library and within view of the 1912 New York Public Library and its lions Patience and Fortitude, who wear expressions that say: “maybe I won’t eat you today,” stands our first remaining classicd 5th Avenue Donald Deskey lamppost. While the usual Deskey post configuration, aluminum posts with one lamp stretching over the street on a curved L-shaped mast, appeared around 1962, the 5th Avenue version was installed in January 1965:

Currently 86 specially designed anodized-bronze poles are being erected on 5th Ave. bet. 32 and 61 St. The design for the Fifth Ave. poles presented many problems, & was worked out only after a year and a half of give-and-take bet. the Dept. & a committee of architects & designers engaged by the 5th Ave. Ass. Writer spoke with Robert H. McKay, chairman of the comm. He is a partner in an architectural firm called the Office of Alfred Easton Poor, 400 Park Ave. Tells about the problems mainly involving the number of special functions the new lighting poles would have to perform. Paul Brodeur, The Talk of the Town, “Shedding Light,” The New Yorker, July 10, 1965.

While the usual Deskey configuration (seen on this FNY page) has one or two masts that fit into the post’s slotted shafts, the 5th Avenue Deskeys feature a modular adaptation at the apex: as many as four slots that can hold lamppost masts, floodlights, stoplights, and fire alarm indicator lamps. The central shaft, seen at left, can hold flags.

The officials had come to the dedication with an American flag to be displayed on the new pole. To their chagrin, they discovered that there was no fixture on which to display the flag at half-staff in tribute to Sir Winston Churchill.

The problem was quickly resolved by a maintenance worker who attached a wire holder to the pole so that the flag could be flown half-staff…

The slender poles will replace the bulky, two-globe, cast-iron lampposts that have lighted the avenue for more than 50 years. The old posts will be junked for scrap.

The design of the new posts, which cost about $800 each, was developed by Robert L. Harmel, chief engineer with the Department of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity, and Robert H. McKay, chief consultant of the Fifth Avenue Association, which paid the city close to $20,000 for various innovations. Theodore Jones, “New Fifth Ave. Lamp Installed and Flagpole Difficulty Solved,” NYTimes, January 27, 1965

At the beginning, they also held small statues of the Roman god Mercury: these were transplanted from 5th Avenue’s classic two-light stoplights, also not seen elsewhere in the city. One of the Mercurys can be seen at the Museum of the City of New York. 5th Avenue pioneered the use of stoplights in NYC, with massive traffic control devices set up in the center of the street as early as the 1920s.

The New York Times described the first 5th Avenue Deskey’s installation on January 26, 1965:

The 30-foot lamppost was raised near the southeast corner of 42nd Street to the cheers of passing spectators and a sigh of relief from city officials, who moments earlier had found themselves with an embarrassing problem:

The city has commissioned the firm of Donald Deskey Associates to design a single all-purpose pole, combining beauty & utility – capable of supporting street lights, traffic lights, fire-alarm signal boxes, police telephones, & street signs. The firm expects to have the specifications ready for approval by June. If approved, the first poles should be in place by the end of the year. A Deskey representative said “seeability” is important – this means adequate pavement brightness, sufficient object brightness, a low level of discomfort glare & a minimum of disability-veiling glare. There are about 106,000 poles in the city now. The majority are at least 40 years old, some are 60 or 70. Those bishop’s crook lighting poles go back to the eighteen-nineties & were intended for gas, not electricity, & have practically no seeability. Being of cast-iron they are expensive to replace. Mr. Donald Deskey himself came in & talked about the poles saying their design would satisfy both traditional & modern tastes. The firm considers this assignment a public service & it will probably cost them three times as much as they’re paid for it. Brendan Gill, The Talk of the Town, “Seeability,” The New Yorker, February 14, 1959

Deskey post, NW corner 5th Avenue and West 42nd Street, January 2008; right, retro-Twin at the SW corner.

Note the above NYTimes article where it says that the “older posts will be junked for scrap.” In the Swingin’ Sixties, the city couldn’t get rid of old designs fast enough, as old Beaux-Arts facades were sanded off or sheathed in flat marble and concrete (like the old Times Tower at One Times Square) or torn down outright, like Pennsylvania Station. Likewise NYC’s legions of ornate cast iron posts were junked.

A funny thing happened in the 1980s, though, as designers realized that these posts were classics, and soon new molds for the old posts were produced and retro versions began popping up everywhere. A new flock of classic Twin designs has been installed ringing Bryant Park, on West 40th and 42nd Streets as well as 6th Avenue…but ironically not on the Twinlamp’s first home, Fifth Avenue!

The 5th Avenue and West 42nd Street Deskey wears the classic orange fire alarm light and also the new red light mounted on the luminaire. Most of the orange lights are being allowed to burn out as the newer ones take over.

Referring to my earlier point about the green Robos, the 5th Avenue Deskeys, I thought, have always had more personality since the S-curved masts are themselves variants from the usual Deskey posts, and they support a wide number of luminaires dating from the early 1970s all the way to the early 2000s.

When first installed, each mast, without exception, carried a General Electric M400 luminaire burning a green-white light. None carried the M400’s great rival, the Westinghouse “Silverliner” OV25 (each seen on this FNY page). The M400’s immediate successor at GE, the M400A2, with the photocell mounted further back, largely replaced the M400 on the 5th Avenue Deskeys and many of these remain today.

After the brief flurry of Deskeys from 40th to 42nd, 5th Avenue returns to the drab Robos for a few blocks between 43rd and 45th Streets. An impressive and historic piece of “street furniture” however has come into view just ahead on the left side at West 44th…

Some timepieces themselves are timeless. 5th Avenue has no less than three historic street clocks: at 23rd (200 Fifth), 59th (783 Fifth) and this 19 foot tall Seth Thomas clock at 522 installed in 1907. It originally stood a block away at the American Trust Company building at 43rd Street; when that company merged with the Guaranty Trust Company in the 1930s the clock was moved north to its present locale. A glance at the ornamentation and detail bespeaks the era when it was made.

The clock has “IIII” instead of “IV” for 4, normal in clock faces. It’s unknown how this tradition arose.

Above: “Mini-me” Robo, the only one of its type on Fifth, near East 46th. RIGHT: Deskey with attached fire alarm lamp and stoplight, West 46th “Little Brazil Street,” so nicknamed between 5th and Times Square for its concentration of Brazilian restaurants, tourist stores and hotels.

Diamond Detail

West 47th between 5th and 6th Avenues was officially designated Diamond and Jewelry Way in 1982. The Fifth Avenue Jewelers Exchange, sponsored by Julius Furst, was opened on Dec. 16, 1948 and was the first precious stones wholesaler to be opened on West 47th; over the years, diamond and jewelry has come to completely dominate the block.

New York’s diamond district, 47th Street from Fifth to Sixth Avenues, has long been hiding in plain sight, an entire block devoted to one trade but without a unifying visual marker. Now, however, the district is distinguished with the installation of diamond-shaped lights at both ends of the block. Howard Abel of Abel Bainnson Butz, the Manhattan architectural firm that designed the lights, said that the fixtures were made of two sheets of translucent acrylic, into which more than 5,000 glass marbles were placed ”so that the lights really sparkle like diamonds.” The cost, about $250,000 for four, was paid by the city. Eli Haas, president of the 1,800-member Diamond Dealers Club, says every merchant he has spoken with is pleased about the instant landmarks. Meanwhile, less fanciful high-intensity lights have been installed along the entire block. ”It’s lighted up like Times Square,” Mr. Haas said. Fred Bernstein, “In The Sky With Diamonds,” NYTimes, June 3, 1999

In addition to the diamond lamps, West 47th also has a mix of smaller theme lamps, as well as the occasional Robo.

Donald Domination

Between 46th and 61st Streets, 5th Avenue remains dominated by the Deskey Twins, though it seems that more are lost every year by attrition. When one is lost, the DOT replaces it from something from its grab bag of posts since the SLECO-manufactured Deskeys have not been made for a couple of decades. hence 5th Avenue no longer has a standard post (at least, on those blocks where the Robo doesn’t hold sway).

Flag-festooned Fifth, as it passes Rockefeller Center and St. Patrick’s Cathedral on the other side of the street, contains a clue toward the Deskeys’ ongoing demise: though short-armed stoplights can be mounted on them, Deskeys have no provision, as the Robos do, to hang the lengthy, guy-wired stoplights that have become more frequent on NYC streets as traffic has become heavier and drivers more aggressive. Above left: a Deskey holds fast the corner before The Rock’s Palazzo D’Italia, and you can see Lee Lawrie’s famed Atlas statue on the extreme right.

Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson’s 1914 St. Thomas Church (Episcopal) takes no back seat to St. Patrick’s in the pantheon of 5th Avenue churches. Lee Lawrie, the sculptor of Atlas, serves a different belief here as he did the ecclesiastical sculptures at the doorway.

On 5th between 49th and 61st the Deskeys appear with some of the world’s great architecture such as Charles McKim’s Florenrtine-style 1899 University Club at West 54th.

As impressive as its exterior, the interior of the building is splendiferous with rich marbles, gilded columns, fine woods and excellent murals by H. Siddons Mowbray. The three most impressive rooms are the reading lounge on the elevated first floor overlooking Fifth Avenue, the magnificent third-floor double-height dining room that stretches the length of the building’s sidestreet frontage, and the enormous, vaulted library.

The facade of the seven-story building is divided into three parts by courses beneath the building’s large cornice. The small windows are residential rooms and the large windows are major club facilities.

Seals of some of the nation’s oldest universities emblazon the facade, which is, according to John Tauranac in his excellent book, “The Essential New York, a Guide to the History and Architecture of Manhattan’s Important Buildings, Parks and Bridges,” published in 1978 by Holt Rinehart Winston, “not limestone, as you might think, but pink Milford granite from Maine.” “There is a slight batter, or receding upward slope to the walls, adding to its austere majesty,” Tauranac noted, adding that elephants are keystone elements in the top row of windows and that mortarboards, the flat, square caps wore at graduating ceremonies, are used as metopes in the entrance entablature.

According to Leland Roth in his monograph on the architectural firm published by Bernard Bloom New York, 1973, Amo Press, New York, 1977, “elements from the Palazzo Spannochi, Siena, and the Palazzo Albergati, Bologna, are freely quoted” in this building designed by Charles Follen McKim.

The club was organized in 1865 to promote the arts and required that all its members have college degrees. When it could not expand its facilities in the Jerome Mansion on Madison Avenue and 26th Street it bought five lots at its present site and commissioned McKim, a member of the club, to design a new 9-story building, several of whose floors are double-height with mezzanines.

Early photographs indicate that the building employed double awnings in its large arched windows. More importantly, a stone balustrade surrounding the base of the building was removed in 1910 when the avenue was widened.

Things change, of course, and in 1987 the club admitted women. Carter Horsley, City Review

Double Deskeys meet Warhol’s Marilyn (left, advertising the Museum of Modern Art) and the Disney empire at East 55th (right)

Midblock Deskey stands between the 1875 5th Avenue Presbyterian Church (left) and the Henri Bendel boutique, a mecca for “Bendel girls” since 1895.

Bendel’s famed etched windows are the work of Rene Lalique (1860-1945), French master of glass and jewelry design, and were installed in what was then the Coty perfume emporium in 1912; Bendel arrived in 1991 and restored the windows, which had gone through several years of neglect.

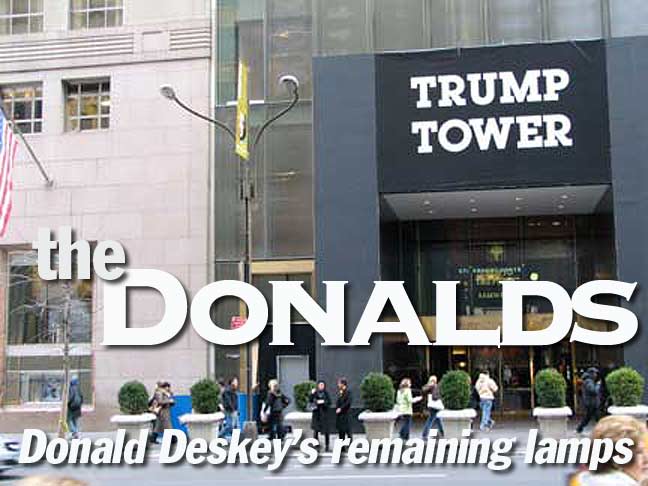

Abercrombie & Fitch, a company that uses photos of mostly unclothed people to sell clothes (have a look) has had an octagonal-shaft pole replace the corner Deskey in an example of lamppost attrition. Most of Donald Trump’s buildings present bland, yet imposing, exteriors and his flagship, Trump Tower, between East 56th and 57th, is no exception. His residence in this building, as Apprentice viewers will remember, is awash in gold, bronze and marble. Planters positioned on the sidewalk outside the building protect the building from any disgruntled contestants.

The Art Deco Bergdorf Goodman Men’s Store at 745 was constructed in 1931 as the Squibb Building and has since been home to F.A.O. Schwartz, the high-end toy store. The translucent -cubed exteriorApple Computer Store, opened in 2006, attracted huge crowds on opening day and only slightly smaller ones now. Each looks even better with a Deskey alongside.

Grand Army Plaza (one of three Grand Army Plazas in NYC) is known for the Plaza Hotel, recently converted to residences, the Pulitzer Fountain, and the gilded William Tecumseh Sherman statue.

It’s also home to a flock of retro Type M Corvington lampposts, which also line all of Central Park South, complete with classic Bell luminaires. Pigeons especially find them handy.

Most of the poles are also outfitted with “mini-me” masts that illluminate sidewalks. These masts remind me of the phenomenon of the parasitic twin, in which an undeveloped twin is attached to an otherwise normal body.

Lombard Lamp, Grand Army Plaza and East 60th Street. From FNY’s Secrets of Central Park page:

This lamp was donated by Hamburg, West Germany in 1979 and is a replica of an ornate lamp found in Hamburg at the Lombard Bridge. The plaque reads “This Lombard Lamp is presented to the people of New York City and by the people of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg so that it may forever brighten a bridge of friendship in human relations, trade and commerce.” It can be found at the west side of Grand Army Plaza on 5th Avenue. A second Lombard Lamp replica was donated to Chicago, which placed it in its Lincoln Square neighborhood in the same year.

This otherwise normal Deskey lamp (in its normal configuration) like all other Central Park streetlamps is painted bright green.

At one time, every corner between 32nd and 61st Streets along 5th Avenue boasted a double Deskey. In 2008 only two streets, 53rd and 60th, claim a Deskey at both corners. The final one, going north, is at the Pierre Hotel at East 61st. Further north, 5th has “normal” single Deskeys.

And before we kick another FNY page in the head, a look at some more unusual lamps: BMT subway entrance lights, and one of NYC’s very few “olive” stoplights, complete with traffic control box (the device that changes the light from red to green). Stand beside one and listen to it click!