By BRIAN BERGER

whowalkinBrooklyn.com

In the world of lesser-known Brooklyn neighborhoods, none is more obscure, or more mysterious, than Highland Park. This is partly the result of geography, nestled as it is in the borough’s northeast corner and partly bad luck: nobody famous enough to represent the area’s hills and history has come from Highland Park. For those who don’t live here, linger over New York City street maps, hang out in cemeteries or ride the J/Z trains out this way, it’s an easy place to miss. Still, there have been some clues.

Eldert Lane station (J/Z), Jamaica Avenue

Blahzay Blahzay CD cover

In his youthful memoir, Walker In The City (1951), Brownsville-native Alfred Kazin mentions nearby Highland Park, as does Michael Stephens in his East New York-centered family novel, Brooklyn Book Of The Dead (1994). Two years later, hip-hop duo Blahzay Blahzay had an underground smash with “Danger,” featuring the hypnotic hook “When the East is in the house — oh my god, danger!” The intersection of Jamaica Ave and Ashford Street is shown a couple times in the video. More recently, an essay in New York Calling (2007) observed:

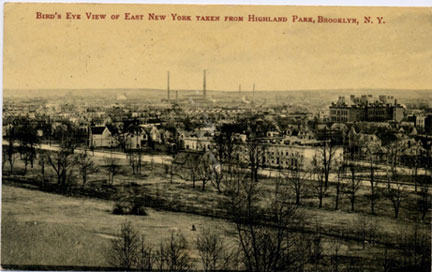

“Brooklyn rises most impressively the water in Sunset Park and again up to Queens from Cypress Hills and Highland Park; on a clear day, you can look across the sprawling flats of East New York and New Lots to the Rockaway peninsula and the churning Atlantic Ocean beyond.”

When I wrote that in the summer of 2006, I was thinking specifically of the view from Miller Avenue and Highland Boulevard. How did we get there?

The town of New Lots was born on February 12, 1852, following its seperation from the town of Flatbush. Although largely agricultural — and, along Kings County’s southern shore, largely uninhabited wetlands — eventually New Lots would include not just its namesake village but the neighborhoods of Brownsville, Cypress Hills and East New York as well. This broad territory remained independent for more than three decades. A week before New Lots’ annexation by Brooklyn, this feat was marked by a celebration. Not all were pleased, however, as can be seen in the epitaph offered by one local office-holder: “To the memory of New Lots, Died August 1, 1886.” For the next fifty years, the former town of New Lots — including what would become known as Highland Park — comprised the 26th Ward of Brooklyn.

The 26th Ward was many things to many people, an unusual number of whom would have a great say in Highland Park’s future, although they themselves were no longer among the living. Cypress Hills Cemetery — to Highland Park’s east — was founded in 1848; The Evergreens, to its west, was organized the year after. Both would limit the future development of the area; likewise the Ridgewood Reservoir (1856-1859), sited atop the same glacial ridge the cemeteries rose to. Ideas for a park in this area date to 1860, when James S.T. Stranahan — the man behind the Atlantic Docks complex in Red Hook and also the single person most responsible for making Prospect Park a reality — advocated its creation but things floundered politically for another thirty years.

As Brooklyn street names are rarely notable for their poetry or humor, let’s begin at the corner of Jamaica and Force Tube. The intersection itself is about halfway between the now demolished Brooklyn Water Works pumping station at Atlantic Avenue between Logan and Chestnut, and the reservoir. Force Tube takes its charming sobriquet from the buried pipe engineers called a force main and which ran up the hill to the Reservoir.

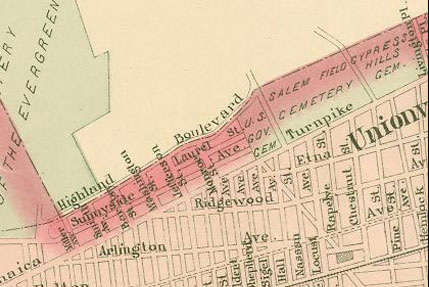

1916 Bromley Brooklyn atlas

It’s little remembered today but the cycling craze of the 1890s was a prime motivator of paving — macadamization — in Brooklyn and Queens, and wheelmen flocked to Jamaica Avenue once it was made rideable, with complaints about the cyclists soon following. A historic convergence of sorts occured on Christmas afternoon 1897, when there was a break in the main running under today’s Highland Place. “Suddenly, and geyser-like, a torrent of water shot upward, carrying with it empty barrels like dritfwood in a torrent,” the Daily Eagle reported.

“In a moment, Jamaica Avenue was flooded. Dr. R.H. Lahy’s drug store, on Jamaica Avenue across the way from Force Tube Avenue, the rendezvous of the neighboring gossips, was in the path of one of the barrels as it bounded against a trolley pole and then struck the framework of the show window of the drug store, making the glassware rattle but doing no further damage. Two belated wheelmen were pedaling along Jamaica Avenue when the flood broke and they caught it at its height. Wheels and riders were upset and the unlucky cyclists drenched to the skin but fortunately escaped further injury.”

While the specifics of the gossip at R.H. Lahy’s are unknown, a letter to the Eagle two years prior is revealing. “Masterless dogs rave and rage by night without interference by the new dog catching bureau, and bicycles infest the sidewalks by day, while pestiferous tramps abound,” the resident of nearby Cypress Hills wrote. “On Sundays, string bands and ‘spielers’ occupy Dexter Park. If the Queens County authorities haven’t the decency to cause laws to be obeyed, surely the nuisance in the city limits could be abated if a few hundreds of the sacreligious vermin of both sexes who yell blasphemies and obscenities along Jamaica Avenue and bombard tombstones with empty flasks were rounded up.” Why did so many ‘vermin’ bring the ruckus here? “The difference between the fare to Cypress Hills and Coney Island means several beers. Hence the influx of dregs,” our correspondent helpfully explained.

The danger of cyclists drafting off trolleys– Jamaica became an “electric road” a few years prior — was another concern, likewise the cars’ effects on domestic animals. To clear the way, trolley drivers used a spring-activated gong, described as “sharp and harsh” sounding. Sometimes, it was noted, the driver “rings it suddenly close by the ear of sleepy dog to the animal’s complete demoralization. Horses do not seem to mind the vehicle so much.” Thus street life in the fast-changing 1890s.

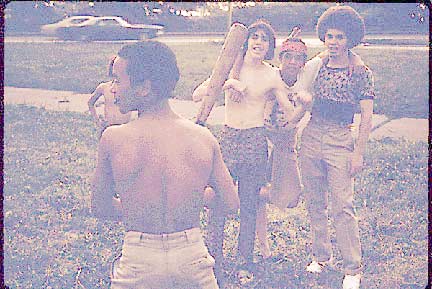

“Kung Fu” and “Puerto Rican Boys Playing Softball in Brooklyn’s Highland Park in New York City”, by Danny Lyon, 1974

Decades later, the great photographer Danny Lyon — perhaps best known to FNY readers for The Destruction of Lower Manhattan (1969) — was in the area, working for the recently-born Environmental Protection Agency’s Documerica project. Some of these images are now accessible via the National Archives, and two in particular stand out. “Puerto Rican Boys Playing Softball in Brooklyn’s Highland Park in New York City,” the description of one 1974 picture reads. “The inner city today is absolute contradiction to the mainstream America of gas stations, expressways, shopping centers and tract homes. It is populated by blacks, Latins, and the white poor. Most of all, the inner city is human beings as beautiful and threatened as the 19th century buildings they inhabit.” Largest among the inscriptions on the cast of the youth with a broken leg: “Kung Fu.”

Although we could, like the Nassau County water of yore, follow the course of the force mains and head up Highland Place — a rise later known as Snake Hill — let’s instead walk west along Jamaica, following the bottom of the park from whence the neighborhood took its name. Pausing at Ashford Street, we lament a significant historical loss: the Judge Teunis Schenck House, built sometime in the 1760s. Originally located a few blocks further east, it was moved here in 1792 and expanded a few times over the years. When the city acquired this land in the early 1900s, the house passed from the Schenck family to the Parks Department; a 1911 postcard from the collection of the East New York Project sites it well. Although they used the Schenck House for a variety of purposes in following decades, none were apparently valuable enough the structure was deemed worth saving, despite its documentation during the WPA’s Historic American Buildings Survey off 1936.

At present, researchers are unsure when the Teunis Schenck House was destroyed, although the mid-1950s is likely. Its loss is all the more frustrating because two other Schenck family homes survive at the Brooklyn Museum. The older one, the Schenck-Crooke (or Jan Martense Schenck) house dates from the 1650s and stood near today’s Avenue U and East 63rd St in Mill Basin. A hundred or so years later, the Nicholas Schenck house was built on land now within Canarsie Park.

Lest there be any confusion over the labor of Brooklyn’s Dutch and English forebears, Alter Armbruster’s History of New Lots usefully offers 1820 Census data. The Teunis Schenck houshold then comprised 11 people and seven slaves; Isaac Snediker, their neighbor, had a family of five, and possessed six slaves.

The next block over from Ashford is Warwick, and there’s an entrance to the park here. Looking at the winding path leading uphill to Highland Boulevard begs the question: did Warwick Street ever run through the park? To keep things brief, to look at ten maps of the 26th Ward from, say, 1873-1929, is a crash course on ambition, competing interests and human fallibility. As farmland was sold, various grids were made, some of which would be memorialized by mapmakers. While things couldn’t get too crazy because the future neighborhood had to– more or less — match up with the rest of East New York below Jamaica Ave, that doesn’t mean people didn’t dream in ways that could confuse us later.

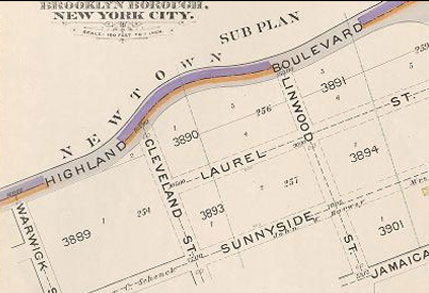

This excerpt from the Chester Wolverton 1891 Atlas of Queens County (left; don’t ask) is a good example. First, it retains the Town of New Lots street names. Of the north-south roads within our purview, only Miller Avenue and Barbey Street would survive. Second, because Highland Park qua park doesn’t yet exist, Highland Boulevard, Laurel Street and Sunnyside all extend east to the cemetery. The street that runs diagonally to — and, for now, stopping ató Jamaica is our beloved Force Tube. In fact, many of the blocks on this map never existed… but some did, and still do. Instead of chasing ghosts (such as those in the EB Hyde’s 1898-1899 Atlas of the Brooklyn Borough, right), this is where we will focus our attention…

Barbey Street

Hendrix Street

Schenck Court

Van Siclen Court

The next block that runs north of Jamaica is Barbey; its handsome homes appear to date from the early 20th century. Why Barbey is a through street when, of the following three blocks– Schenck, Hendrix and Van Siclen — only Hendrix goes through to Sunnyside Avenue is unclear.

The others dead-end into the private Schenck and Van Siclen Courts respectively. What’s “private” mean on the open road? No parking and that local residents are responsible for maintenance.

Miller Time

Miller Avenue — possibly the steepest street in Brooklyn — looking south from Sunnyside Avenue (above) and north from Jamaica Avenue (right)

Turning onto Miller Avenue, we begin one of the most dramatic, two-block ascents in all Brooklyn. The first block is a relatively shallow rise up to Sunnyside and, pausing here is an excellent way to survey much of what the neighborhood offers. Down the hill, East New York starts to spread before us, with the elevated tracks above Fulton Street prominent. This part of today’s J/Z line was completed in 1893 and was such a big deal for the 26th Ward, its opening was occasion for a “mass meeting and jollification.” Brooklyn Mayor Boody and numerous others spoke.

NewYorkShitty on Mayor Boody’s Newtown Creek inspection, 1892

Between Sunnyside and the crest along which runs Highland Boulevard are only two structures on Miller Avenue. We saw the upper floors and towers of this large brick apartment building while gazing up from Van Siclen. The house across the street is likewise striking, with a stone retaining wall and a stairway that recalls the Bronx or Staten Island. Looking west is one long block leading to the Sunnyside’s intersection with Vermont Street. It too is a remarkable view for Brooklyn, half homes with long stairwells perched on the hill, a near panoply of early 20th century Brooklyn building styles. We’ll review these later but for now, let’s double-back on Sunnyside, heading towards the park.

Keep on the Sunnyside

On the south side of the street is a run of neart, mostly attached houses, some festooned with the Puerto Rican flag. Most of these residences, as well the similar homes we saw inside the dead end Courts fronting Jamaica Ave, were built by an outfit called Richard’s Real Homes in the early 1900s. Looking north, the red brick apartment building and its retaining wall dominate, and a no dumping sign pleads the embankment’s cause of refuse civility to mixed results. At Hendrix Street, some rather undistinguished architecture is at least a little amusing in that its front facade matches the rear of the equally uninspired homes above it on Highland Boulevard.

Upon reaching the corner of Sunnyside Ave and Sunnyside Court, we heed words of hillbilly music icons, The Carter Family: “Keep On The Sunny Side.” The Carters — then comprised of A.P., Sara and Maybelle — recorded A.P.’s song twice, the first occasion for Victor, in Camden, NJ in 1928; the second for ARC at 1776 Broadway on May 8, 1935. As for whether the Carters knew the Brooklyn intersection of which they sang, history is mute.

Sunnyside Avenue continues to its entrance to Highland Park, while Sunnyside Court dead ends into the hillside. But did it always? Nearly all the old maps say no — Laurel Street was here — so let’s return to Barbey St. and see what’s left from that perspective.

Sunnyside Court

Sunnyside Avenue dead-end at park entrance

Barbey Street at Sunnyside Avenue

Barbey Street dead-end curve north of Sunnyside Avenue

The homes, which rise up Barbey from Sunnyside, are a wonder of Brooklyn; the way Barbey lurches right in the middle of the hill, a great puzzlement. As for Laurel Street, despite the evidence of the 1907 Bromley Brooklyn atlas, between possible grading and overgrowth, it’s hard to discern if it actually existed. Similarly, although this reporter has, in many cases, spent as much time thinking about the sewers of Brooklyn as Ed Norton himself, even here, in the true underground of history, numerous dark passages remain, and, alas, Laurel Street is one. (Re: Ed Norton, Brooklyn didn’t build its sewers for fun but, rather, a growing population; thus you can’t know Brooklyn, truly, if you don’t know shit.)

The mysterious Laurel Street at the Barbey curve on the Bromley atlas, and overhead google photo which may show its path.

Barbey makes sharp turn upwards and, after bounding up a flight of stairs, we finally emerge upon Highland Boulevard. Co-named in honor of Vito Battista (1908-1990), a Bari, Italy-born architect, former State Assemblyman and frequent Mayoral candidate, Highland Boulevard to the east skirts the southerly edge of Ridgewood Reservoir then twists back down to Jamaica Avenue. Were we to turn north on Vermont Place before the descent of Snake Hill, we’d pass the western embankment of the reservoir and soon be in Queens. Today, we’ll do neither and instead zip across Highland Boulevard from Barbey to… Barberry.

I believe this was somebody’s idea of a joke — and a pretty good one at that. Despite its prior zig-zag up the hill, there is no reason Barbey couldn’t continue and, in looking for street names, the gentle parody from Barbey to Barberry seems too obvious not to be intentional. (Imagine if Carroll Street in South Brooklyn was called Coral or Corral only between Columbia and Van Brunt?) As for the barberry bush (berberis vulgaris), it does not seem to grow in any special abundance here.

Robert Street. While it’s easy to mistake Barberry for a dead end, a walk to its terminus confirms this wasn’t always the case. Although Robert Street is less than a goat path today, here it is: just as maps suggested it’d be. As with the lost Laurel Street, Robert seems unnecessary, except as an alleyway for the houses fronting Highland Boulevard.

The most interesting thing about Robert St — besides its existence — is the security atop the last stretch of wall: barbed wire is commonplace, of course, but broken, carefully mounted glass shards too? In a certain light, it’s quite striking but what’s being protected here, and from whom?

Continue to Highland Park Part 2