Kew Gardens Hills is not really close to Kew Gardens (across Flushing Meadows’ Willow Lake), is unexceptional architecturally, and is perhaps better remembered for its celebrities, songsters Paul Simon and Art Garfunkeland actors Fran “The Nanny” Drescher andMartin Landau.

It does have its moments architecturally though, here and there, as we’ll see. However the neighborhood is nothing like the one depicted by Simon as his boyhood home in “My Little Town”, where he talks about ‘flying my bike past the gates of the factories’ since there have never been any factories in this residential neighborhood located between Mount Hebron Cemetery and Queens College on the north, the Van Wyck Expressway on the west, the Grand Central Parkway on the south, and Kissena and Parsons Boulevards on the east. Simon’s song could be construed as a devastating putdown of his boyhood home, with the line “nothing but the dead and dying in my little town,” but describing it with factories could have been his way of making clear the song was an allusion, not a history. Describing Simon’s state of mind is ‘above my pay grade’ as Barack Obama would put it, so, as usual, I’ll do a short history of the place and show you around a bit.

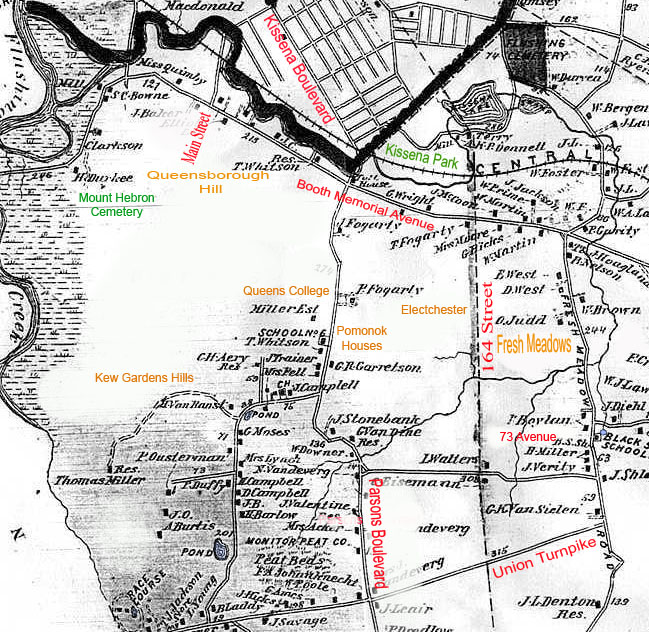

Forgotten Fan and contributor Sergey Kadinsky provided a Beers map of the area in 1876; he has notated in red and orange some current place names. In the colonial era it was a salt marsh and a swamp (adjoining Fresh Meadows is so named because its waters were nonsaline). The area was known as Queens Valley or Head of Vleigh (the Dutch vly means marshy meadow). The whole area was owned by Edward Furman in the 1700s (the Furman family looms large in Queens in colonial times, as Jonathan Furman owned property in Newtown at the same time). Queens Valley was farmed for generations, with farmers using Head of Vleigh Road (today’s Vleigh Place) and Jamaica Road (now Kissena Boulevard) to bring goods to east-west roads connecting the East River with eastern Long Island.

The Queens Valley Golf Club, Pomonok, and Arrowbrook Golf Clubs occupied most of the region in the 1930s, when developers Abraham, Leon and Martin Wolosoff, who had already built large sections of Kew Gardens and Forest Hills west of Flushing Creek, took note when the IND Subway was extended along Queens Boulevard. The Wolosoff brothers set to work purchasing land and building acres of residential homes along Main Street, which was extended south from Flushing in the 1930s. In the 1960s, Orthodox Jewish families moved in (an area hotspot oveer the last decade is a kosher ice cream parlor, Max and Mina’s, on Main Street — you wil foind garlic ice craem there, amongst more conventional flavors) and the area is preternaturally quiet on Saturday, which, of course, was the day I chose to explore…

Alighting from the Q46 bus at Union Turnpike and Parsons Boulevard I immediately spotted..

This round-ended building on Parsons south of Union Turnpike is the “T building” of Queens Hospital Center (nee Queens General Hospital) and was originally known as Triboro Hospital, a tuberculosis treatment facility, built c1939-1940.

With its airy wings and sun-drenched balconies it was intended for the then favored treatment of tuberculosis (TB or “consumption”), plenty of fresh air and light. It is similar in architecture to city hospital pavilions constructed on Welfare Island (Goldwater Hosp) and North Brother Island (Riverside Hosp). –ForgottenFan Al Trojanowicz

St. Nicholas of Tolentine Church was established in Queens in 1916, but the present structure appears to be from the 1950s or 1960s. My high school Latin is … well, nonexistent by now; what does the mosaic say?

“The salvation of the soul is the supreme law”

Parkway Village

Parkway Village, on an uneven 6-sided plot generally between Parsons Blvd., Goethals Avenue, 150th Street, Union Turnpike, Main Street, and Grand Central Parkway, reminds me of a larger version of my own development in Little Neck, Westmoreland Gardens, in that it’s grassy, shady and populated by square, stolid brick buildings. 109 two and three story buildings are interspersed in the development, which has its own streets (Charter and Village Roads).

Parkway Village was built to house United Nations employees. Way out here, you say? Before its present complex opened on the East Side in 1950 the UN was located in the New York City pavilion in Flushing Meadows, a building left over from the 1939-40 World’s Fair, and then in Lake Success in Nassau County; it was a quick trip along Grand Central Parkway.

PV is being considered as a NYC Landmark.

Regency Gardens at Union Turnpike and Main Street, catercorner from Parkway Village, was constructed in 1940, one of many of this type developments in Kew Gardens Hills.

The octagonal-shaft double twin mast post, classified in the Welsbach (a major roadway lighting firm), handbook of NYC street lighting as the Type 12T twinarm, is becoming rarer in NYC, but there are still a flock of them along Union Turnpike. Carl von Welsbach (1958-1929) was an Austrian scientist who assisted in the development of the modern lightbulb.

Vleigh Place, which today runs from Union Turnpike between 138th and 141st Streets northeast to 70th Road just east of Main Street, was formerly one of the only north-south routes in Queens Valley in its former role as Head Of Vleigh Road.

At present, it is the only street in NYC whose name begins with VL.

ABOVE: homes on Vleigh Place at Union Turnpike (left) and just north.

The new Queens, shed of its bourgeois grass lawns, on 78th Drive near Vleigh Place.

Zachary Taylor sports bar eh? What’s with the trend of naming bars and restaurants after mediocre mid-19th Century presidents like Old Rough And Ready, or like Millard Fillmore‘s in Fresh Meadows near Queens College?

QCSB

When the Queens County Savings Bank, at Main Street and 76th Avenue, was constructed in 1953, it was meant to be a replica of…

Independence Hall in Philadelphia. In fact, it has a Liberty Bell model in the lobby.

The bank has one of Queens’ best 4-sided clocks (note the traditional clock Roman numeral “IIII” instead of “IV”. All QCSB branches work in a black and gold color motif, one of your webmaster’s favorite color combos (my bathroom is in black and gold, but I’m not a Steelers fan).

Freedom Square and the Theodor Herzl flagpole, Vleigh Place and Main Street.

The City of New York acquired the site by condemnation in 1954. The park was designed in 1957, and the bank contributed $25,000 for its construction and maintenance in 1958.

In March 1960 the property was named Freedom Square by the City Council. Citizens and politicians gathered at the site that May to dedicate a flagpole which commemorated the centennial of the birth of Theodor Herzl. A Hungarian Jew, Herzl (1860-1904) was the founder of modern Zionism. He supported the establishment of a Jewish national state and organized the first Zionist World Congress in 1897, serving as its president until his death. NYC Parks

Ames Street in Brownsville, Brooklyn, had been renamed for Herzl in 1913.

Glass-lobbied building at 75th Ave. and Main has some handsome white & black enamel signs.

In the 1800s and early 1900s when all of KGH was farmland, 75th Avenue was called Quarrelsome Lane.

73rd Avenue, a main east-west route from Kew Gardens Hills all the way east to Bayside, has existed as well since colonial days when it was called Blackstump Road. It has had a bike lane for a long time, but it has yet to get the deluxe green-stripe treatment.

73rd Avenue, a main east-west route from Kew Gardens Hills all the way east to Bayside, has existed as well since colonial days when it was called Blackstump Road. It has had a bike lane for a long time, but it has yet to get the deluxe green-stripe treatment.

Main Street Cinemas, Main Street at 73rd Avenue. Would you believe this is now a six-plex? Some of the theatres have just 50 seats. Fran Drescher worked here before breaking into showbiz.

73rd Avenue and 150th Street. Consider the contrast; a project east of 150th has been given a jaunty aluminum cladding, while stolid brick still marks the Kew Gardens Hills Apartments.

You can have your pick here, robin’s egg or burnt orange.

My cousin and her family lived on 76th Road just east of 150th in the early to mid 1990s, and her house faced a large empty lot that the neighbors said had been that way from time immemorial. In the early 2000s, Touro College purchased the property and Lander College for Men and the gi-normous luxury apartment complex, The Opal, have been built there.

Kissena Boulevard begins its run to downtown Flushing, or ends its run from Flushing, at Parsons Boulevard. Kissena, and Parsons heading south from here, were once known as Jamaica Road and it was the most direct method of getting between the towns of Flushing and Jamaica in the 1800s and into the 20th Century.

The country of origin, Afghanistan, of the proprietors of Kouchi Supermarket is depicted on the sign. Queens’ highest concentration of Afghan Americans is here in Kew Gardens Hills.

Scroll up and take a look at that 1876 Kew Gardens Hills map again — in the middle, see that bend in the road just below the words Stonebank and Van Dine? That bend is still there; it’s now called Aguilar Avenue. The old Kissena Road took a bend east and then south again on its way to Jamaica (probably to avoid a swamp). I have old maps from the 1920s and 1930s, and it’s renamed Aguilar Avenue as early as then. Aguilar is a Spanish name, but other than that I have no idea who this street commemorates. How do the localas pronounce it? Agg-ee-ar, as in Spanish, or Ag-will-ar, as in English?

Why note the Pathmark market at Kissena Blvd. and Aguilar Avenue? There’s a classic NYC parkways woodie post in the parking lot.

Officially classified by Welsbach as either a Type 34 or Type 35 twinarm — depends on the height — these posts once dominated the roadways constructed by Robert Moses in the 1930s by the tens of thousands. They lit Shore Parkway, Cross Island Parkway, Laurelton Parkway, Grand Central Parkway and other roads in NYC and Long Island, and found their way, on occasion, to some main roadways such as Rockaway Freeway on the Rockaway peninsula.

When I first surveyed them for FNY in 1999, a few remained in place on NYC’s parkways, but today (2008) one, and only one, remains in place and that one is on the Belt Parkway just west of Laurelton Parkway in southern Queens.

These posts are not carrying Westinghouse AK-10 “cuplights” — these just resemble them. As you can see some incandescent bulbs are still there, but I do not know if they light up at night.

Kissena Farms, Kissena Blvd. near 71st Avenue, and its cornucopia artwork.

My friends who are more politicized than I am bemoan my lack of passion for that kind of thing one way or another. But I can get pretty worked up about the Department of Transportation’s dopiness (don’t get me started about spending $4 million during a recession to change all the Triboro Bridge signs to “Robert F. Kennedy” signs). In its zeal to commemorate the late labor leader, Harry Van Arsdale Jr. (1905-1986), who created tthe nearby Electchester housing project (see below) the DOT insists on placing the lengthy name on the same sign as its original name, Jewel Avenue, making both names illegible.

Formerly, the city would simply rename a street if it wanted to commemorate someone (7th and 8th Avenues north of Central Park were simply renamed Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Blvd. and Frederick Douglass Blvd., respectively) and of late, a separate sign has been used when the city wants to honor someone (as in firefighters killed during the World Trade Center terrorist attack) but here, the city is adamant about same-sign placement, even doing so on newer signs placed on stoplight crossarms. Idiocy.

Jewel Avenue itself is a fascinating remnant of NYC street nomenclature. Sergey:

In Forest Hills, from 75th Avenue to 63rd Drive, [19th Century Forest Hills developer] Cord Meyer gave northern Forest Hills an alphabetical street grid ranging from Atom toZuni. Unlike southern Forest Hills, which had purely British names such as Austin, Burns, Clyde, and Dartmouth, northern Forest Hills had diverse names such as Euclid,Meteor, Nome, and Pilgrim. The five blocks between Zuni and the future Long Island Expressway were also given names. The street following Zuni was named Omega, after the last Greek letter, signifying the edge of the neighborhood … By the late 1920s, the city decided to assign numbers to the streets and only Jewel Avenue remains from this whimsical naming sequence.

Jewel Avenue is also the only street from the Cord Meyer Forest Hills naming scheme to be extended over Flushing Meadows and into Kew Gardens Hills and Hillcrest, extending out to 73rd Avenue and 179th Street. Oddly the street’s width varies widely, from the 6-lane behemoth you see above to two lanes east of here that abruptly change to four lanes and then back to two, depending on which block you are. Evidently, the city one thought to expand Jewel Avenue into a main thoroughfare east of here at one time, but the plans went by the boards.

At Jewel and Parsons, you come upon a properly intimidating concrete-cladded building. Note how the windows are offset from each other, creating a varied look; the architect had some imagination. In keeping with the heavy union theme in this area, the Amalgamated Bank of New York was started in 1923 by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America and remains the only union-owned US bank in operation.

Note that the building, which hosts the Electric Industry Center as well as the bank and the Pomonok Branch of the Queens Borough Public Library, dispenses with a Jewel Avenue address in favor of the Van Arsdale name. The labor leader rose to prominence in the IBEW, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers.

Electchester, a cooperative housing project located between Jewel/HVA Avenue, Parsons Blvd., 164th Street and 65th Avenue, was established by Van Arsdale and the Joint Industry Board of the Electrical Industry in 1949 on the grounds of the old Pomonok Country Club. Originally housing mostly electrical workers and their families (hence its name), Electchester is no longer exclusive to them:

The meat cutters had Concourse Village in the Bronx. The garment workers had Seward Park Houses in Manhattan. The printers had Big Six Towers in [Woodside], Queens. Decades ago, local unions sponsored more than a dozen cooperatives that provided almost 50,000 decent and affordable apartments to working-class families. As the power of labor waned and real estate values skyrocketed, though, most of these co-ops either lost their direct union connection or allowed their shareholders to sell their units on the open market. New York Times, March 15, 2004

Photographed June 2008; page completed November 9, 2008

erpietri@earthlink.net

©2008