Forgotten NY has always supported mermaid-themed art (currently I’m compiling a page full of mermaids used in posters, architecture and advertising) and Beaux-Arts sculptors and architects have also, from the looks of things, been fond of homo ichthyus as well; in the New York Botanical Garden, the Lillian Goldman Fountain of Life and Queens’ much-derided Civic Virtue, at Borough Hall, use the fishtailed maidens (though in the latter, they represent vanquished evil). After a lengthy Manhattan-Bronx bridge walk in May 2009, here’s one more.

Ernst Herter’s 1893 fountain statue in honor of Heinrich Heine, author of Die Lorelei, was originally rejected by Düsseldorf, the German city of Heine’s birth (for anti-Semitic reasons, some say). A coterie of affluent German-Americans purchased the work and offered to place it in Grand Army Plaza in Manhattan. That site, too, was rejected, and the fountain was ultimately placed in Joyce Kilmer Park at the Grand Concourse near East 164th Street around the turn of the 20th Century. In the early 2000s the fountain has been fully restored to a brilliant white, given a new iron railing and moved to East 161st Street across from the Bronx County (Mario Merola) Courthouse.

A profile of Heinrich Heine can be seen on the north end of the fountain.

The sculptural group, carved out of white Tyrolean marble, depicts Lorelei, a German mythical figure seated on a rock in the Rhine River among mermaids, dolphins, and seashells. According to legend, the maiden was transformed into a siren after throwing herself into the river. She could be heard singing from a rock along the river, her voice hypnotizing sailors to sleep, and then to their death. The bas-reliefs around the pedestal include a profile of Heine. Other decorative and allegorical motifs include a frog, a bird, and a skull symbolizing mortality.

The fountain was purchased by a committee of German-Americans in 1893 and dedicated at the south end of what was then known as Grand Concourse Plaza on July 8, 1899. It was moved to the park’s north end in 1940. In 1999 the monument was restored through the Municipal Art Societyís Adopt-A-Monument Program, with $310,000 as a gift from the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation. It was relocated to its original position in a newly landscaped setting in the south end, funded by Bronx Borough President Fernando Ferrer and Council Member Pedro G. Espada. The rededication ceremony was held on the centennial of the original installation, July 8, 1999, with a keynote speech by Wolfgang Scheffler, Deputy Mayor of Dusseldorf in Germany. NYC Parks

View from the Lorelei Fountain plaza to Old Yankee Stadium in May 2009. The field remained in place as Heritage Field, but the Stadium finally came down in 2010.

The Bronx County Mario Merola Courthouse (officially Bronx County Building) was designed by Joseph Friedlander and Max Hausle, one of NYC’s great Moderne buildings, was built from 1931-1935. The sculptures by the steps are by Adolph Weinman(1870-1952), perhaps remembered best for the “Walking Liberty” half dollar and the “Mercury” dime. He also worked on sculpture the Prison Ship Martyr’s Monument in Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn, and the old Pennsylvania Station. This building is not to be confused with the Bronx Borough Courthouse, now awaiting reclamation further east on East 161st and Third Avenue.

Concourse Plaza Apartments, NE corner East 161st Street and the Grand Concourse as seen from Joyce Kilmer Park.

The Grand Boulevard and Concourse is celebrating its centennial in 2009 . I revisited it the next year:

https://forgotten-ny.com/2011/10/back-on-course-revisiting-the-grand-concourse/

and

https://forgotten-ny.com/2011/10/grand-concourse-part-2/

A Man Named Joyce

Joyce Kilmer Park is a green rectangle between East 161st, & East 164th Streets, Walton Avenue and the Grand Concourse. The former Concourse Plaza was renamed in 1926 for New Brunswick, NJ native Alfred Joyce Kilmer, poet and journalist best known for “Trees,” written in 1913. Enlisting with the Army during WWI, he was killed in action on the Western Front in 1918 as part of the famed “Fighting 69th” Regiment. The author preferred to use his middle name, the surname of his mother’s family (see Comments). He is also notably remembered by a plaza at Quentin Road and Kings Highway in Midwood, Brooklyn, and by a park and avenue in his native New Brunswick.

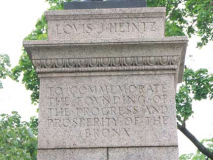

You might expect to see a statue of French architect Louis Risse somewhere along the Grand Concourse, since it was he who designed and oversaw the great road’s construction between 1902 and 1909, but instead, we have a meorial to the early 20th Century Commissioner of Street Improvements Louis J. Heintz, who began arguing for the road as early as 1890. The statue was sculpted by Frenchman Pierre-Luc Feitu and it was installed when The Conk opened in 1909. Risse, meanwhile, is remembered by a one-block street near The Concourse’s northern end at Mosholu Parkway.

The Bronx Museum of Art is featuring a Grand Concourse exhibit throughout most of 2009.

Larrupin’ Lou

Lou Gehrig Plaza, at the center mall on East 161st between The Conk and Walton Avenue, was redesigned in 2003 to replace old Babe Ruth Plaza, which has been subsequently moved to the southern end of the New Yankee Stadium (seen above) on 161st west of River Avenue. (Have you ever thought the nicknames of the Yankees’ two greatest sluggers (no offense, Joe, Mickey, Reggie and A-Rod) were a little, ah, contrived alliteration? When was the last time you heard the word larrup when it wasn’t associated with the Iron Horse? Swat is what you usually do to flies, but the immortal Babe, a Sultan of his craft, couldn’t be the Sultan of Homers or the Sultan of Line Drives. Actually, Slam would have been better as in the Sultan of Slam. They just don’t give out great baseball nicknames anymore, like Le Grand Orange. To look at Lou Gehrig’s and Babe Ruth’s career statistics, you’d think Kal-El and Hercules were playing, and they did this without performance enhancements other than hotdogs, women and beer (Ruth) and conditioning (Gehrig)

Lou Gehrig Plaza, at the center mall on East 161st between The Conk and Walton Avenue, was redesigned in 2003 to replace old Babe Ruth Plaza, which has been subsequently moved to the southern end of the New Yankee Stadium (seen above) on 161st west of River Avenue. (Have you ever thought the nicknames of the Yankees’ two greatest sluggers (no offense, Joe, Mickey, Reggie and A-Rod) were a little, ah, contrived alliteration? When was the last time you heard the word larrup when it wasn’t associated with the Iron Horse? Swat is what you usually do to flies, but the immortal Babe, a Sultan of his craft, couldn’t be the Sultan of Homers or the Sultan of Line Drives. Actually, Slam would have been better as in the Sultan of Slam. They just don’t give out great baseball nicknames anymore, like Le Grand Orange. To look at Lou Gehrig’s and Babe Ruth’s career statistics, you’d think Kal-El and Hercules were playing, and they did this without performance enhancements other than hotdogs, women and beer (Ruth) and conditioning (Gehrig)

I thought I noticed something different about the metal Lou Gehrig Plaza sign — the verdigris has been removed, and it looks brand new! A company called Metal Man Restoration restored both the Gehrig and Babe Ruth plaques. The Ruth plaque has been relocated to the new Babe Ruth Plaza on the north side of West 161st at the new Yankee Stadium.

Page completed May 17, 2009; rev. 11/28/15

3 comments

A typo in the section on the Louis J. Heintz memorial in the Bronx – I believe you meant 1880, not 1980. Love your website, keep it going please!

Andy

Fixed. I’m always doing that.

Hi, Kevin:

Thank you for including some of Joyce Kilmer’s background. One refinement is recommended. You state: “The author preferred to use his middle name, the surname of his mother’s family.” You are correct that he preferred to use his middle name instead of his first (Alfred). But “Joyce” was not the surname of his mother’s family. “Alfred” and “Joyce” were taken from the two ministers in the Kilmer family’s Episcopal church in New Brunswick — the Rev. Alfred Taylor and the Rev. Elisha Brooks Joyce.

If you expand the background of the origin of “Trees,” you may want to state that a century of controversy on this point ended in 2013 when the Joyce Kilmer Society of Mahwah (NJ), which I founded, proved conclusively from family documents (including the little notebook in which the poem was written and dated) that “Trees” was penned in Kilmer’s Mahwah house on February 2, 1913 in a room with a desk and window “looking down a wooded hill.” His wife, Aline, was an eyewitness to history who actually wrote down the words as Joyce dictated them. A letter she later wrote to a student in Chicago said she definitely remembered the poem was written in their Mahwah house. We located the letter and the notebook in the library at Georgetown University (Washington) where the family donated boxes of papers of Kilmer’s history and legacy.

Thank you again.

Alex Michelini

(201) 831-0171

Retired reporter/editor, NY Daily News