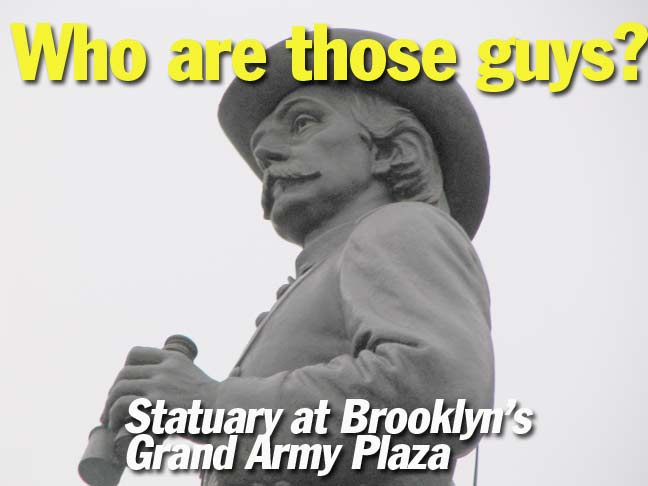

On a drab 15-degree January day in 2010 I made my way up Flatbush Avenue and grabbed the statues that ring Grand Army Plaza, where Flatbush meets the northern end of Prospect Park. We find some usual suspects, and some wild cards as well.

Tucked away on Plaza Street East and St. Johns Place, across the street from a Richard Meier glass cube building that looks like nothing else at Grand Army Plaza, is a big boulder with a bas relief of Henry W. Maxwell. Inscribed below his likeness is: “This memorial erected by his friends is their tribute to his devotion to public education and charity in the City of Brooklyn” and is signed “A ST G” — Irish-born Augustus Saint Gaudens, one of the more prolific and famed sculptors of the 19th Century: the Peter Cooper statue at Cooper Square, the William Tecumseh Sherman statue at Manhattan’s Grand Army Plaza, and the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial at Boston Common and many, many others. Maxwell (1850-1902) was a banker, philanthropist and supporter of public education; he was Brooklyn’s Park Commissioner in 1884. The monument was dedicated in 1903 by Maxwell’s niece at what was then the Mt. Prospect Library at Eastern Parkway and Flatbush Avenue, now the Brooklyn Central Library. It was moved to this location in 1912 and stayed there until the 1970s, when repeated vandalism caused the Prks department to put it in storage. It was restored and put back in 1997.

There were a lot of guys with weak chins running around in the 1800s who overcame this handicap. This heartens me.

General Henry Warner Slocum can be found a little south of Maxwell at Plaza Street East just before it reaches Eastern Parkway. Slocum (1827-1894) was a lawyer and politician in upstate Onondaga County before entering battle in the War Between The States; eventually attaining the rank of general, he fought at Bull Run, Georgia, the Carolinas and Gettysburg, where his leadership was not without controversy. In 1866 he moved to Brooklyn and was twice elected a US Representative, in 1868 and 1870. Unfortunately, Slocum’s name is most recognizable as the steam excursion vessel that caught fire in the East River in June 1904, killing over a thousand German immigrants in the greatest NYC death toll in one day before the events of 9/11/01.

Sculptor Frederick MacMonnies is well-represented in NYC by Slocum, the Quadriga and Army and Navy bas reliefs on the Grand Army Plaza arch, James Stranahan, the “father of Central Park” (see below), Nathan Hale in City Hall Park, and the infamous, controversial Civic Virtue at Queens Boulevard and Union Turnpike.

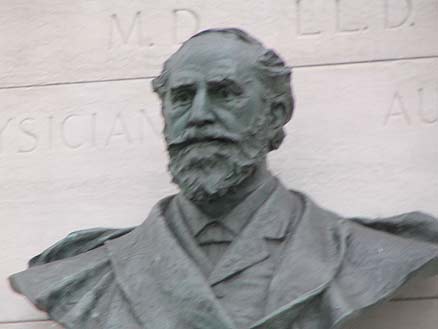

Located at Plaza Street East and Flatbush Avenue is the only bust in NYC of a gynecologist, Alexander Skene (1838-1900). (There’s a statue on the Central Park side of 5th Avenue of James Marion Sims, a second gynecologist). Born in Aberdeen, Scotland, he worked in Toronto, ON and Michigan and served in the Civil War as a surgeon in South Carolina and New York, settling in Brooklyn after the war. He became an adjunct professor at Long Island College Hospital in 1865 and rose to president of the school, serving from 1893-1899. He was founder of the American Gynecological Society in 1866. He discovered the pair of para-urethral glands that are today called the Skene glands.

After his death Scottish sculptor John Massey Rhind created this heroic bust. Skene was an amateur sculptor himself, creating a bust of Sims that is today located in the Kings County Medical Society.

Sculptors operating in the 19th Century and early 20th had an enthusiasm for portraying scenes from classical myth; there were many opportunities to show sea scenes, and the denizens therein — think of the unnamed terra cotta artists who created the Coney Island Child’s Restaurant , or the Lillian Goldman Fountain of Life at the NY Botanical Gardens in the Bronx. Probably NYC’s finest example in the genre is the Bailey Fountain, in the pedestrian plaza directly in front of the Grand Army Plaza Arch. For centuries artists have disagreed on how to show Neptune. He always carries a trident. Does he have a tail, like the merpeople? Legs, like his brothers, Jupiter and Pluto? In this case, sculptor Eugene Savage (whose name is inscribed on the fountain along with architect Edgerton Swarthout) compromised and gave him a pair of scaly legs. We might imagine that the Sea God changed his appearance to suit his needs at a particular moment.

The Bailey Fountain, named for Frank and Marie Louise Bailey, who made extensive donations ($125,000, in the millions in 2010 money) for a new fountain in Grand Army Plaza that would replace two previous ones on the site, is a relatively new piece of classical sculpture — it was completed in 1932. It took $2M to restore the fountain in 2002.

Neptune does not dominate the proceedings here, though, as there are two male and female figures standing on a ship’s prow, symbolizing Wisdom and Happiness. The fountain is spectacular in season when it is turned on and is surrounded by water jets.

“Wisdom and Happiness” are accompanied by an unnamed child as well as a pair of conch blowing mermen. Fishes and frogs are scattered about the ship.

A depiction of General Gouverneur Kemble Warren (1830-1882) can be found at Flatbush Avenue and Union Street. A surveyor and engineer by trade, he arranged a last minute defense at Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg; while he was regarded as an architect of the Northern victory there, he was less successful at the Battle of Five Forks in Virginia and was relieved by General Philip Sheridan.

Warren was born in Cold Spring, NY. He remained in the Army after the war, working in surveying and harbor improvements. Another statue of Warren was erected at Round Top at Gettysburg, on the 6th anniversary of his death.

Rendered here, in a elegant standing portrait by Henry Baerer, Warren’s pedestal includes a slab taken from the very outcrop on which he won his glory, a gesture recalling the granite block that the 14th Regiment brought back from Gettysburg. — Out of Fire and Valor, Cal Snyder. Baerer’s statue was dedicated June 26, 1896.

The statue was a gift of the Warren Post No. 286 of the New York Department of the Grand Army of the Republic, the grass-roots veterans organization, as part of a concerted effort to rehabilitate Warren’s image, which took a beating during the latter stages of the war. In short, the controversy began at Five Forks, during the final weeks of the war. Warren’s troops are roundly regarded as having clinched the Union victory there, but his commanding officer, Gen. Philip Sheridan, thought Warren acted too slow and relieved him. The overall Union commander, Gen. Ulysses Grant, apparently took Sheridan’s side, stonewalling Warren’s efforts to restore his reputation even when Grant was president. Warren was eventually exonerated by a court of inquiry, though; unfortunately for Warren, the judgment was reached about six months after he died. — New York City Statues

Prospect Park is, in good part, the brainchild of railroad builder James Stranahan (1808-1898), who headed a board of commissioners selected by New York State in 1859 to investigate areas to build a public park in Brooklyn similar to the one then under construction in Manhattan. Seven proposals were offered, including Ridgewood and Bay Ridge, which were then not in the city of Brooklyn proper. Another was on a hill called Mount Prospect, on the road that would become Flatbush Avenue near the Brooklyn-Flatbush town border. This location was selected, and the commissioners selected Egbert Viele, who was chief engineer of Central Park, to begin work on the project.

But Viele’s designs were torpedoed by the outbreak of the Civil War. At the conclusion of hostilities, the plan was placed in the more than capable hands of Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, who had landscaped Central Park before the war. Prospect Park was completed by 1870. (Viele’s consolation prize, after a fashion, is that his 1865 map of Manhatan’s underground waterways is still in use today by architects and engineers.)

The statue, by Frederick MacMonnies (see above) was dedicated June 6, 1891; Stranahan was present.

The triumphal arch at Grand Army Plaza, the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, needs no introduction, but there are a couple of tidbits about it that you may not have known. It has a working elevator, for example, and there are two reliefs on the each side of the arch by artists William O’Donovan (Abraham Lincoln and U.S. Grant) and Thomas Eakins (their mounts). The Lincoln sculpture is said to be the only known portrait of Lincoln on horseback. General William Tecumseh Sherman laid the cornerstone in 1889 and the arch was unveiled on October 21, 1892; these portraits arrived in 1894. They were excoriated by art critics at the time.

The Man Who Isn’t There. A bust of President John F. Kennedy by Neil Estern was placed on this stele in 1965, a year after the president’s assassination, and it was removed, ostensibly for renovation, in 2003. It has never returned, though, and today can be found in the Picnic House in Prospect Park.

Here is a short version of the complicated story. Neil Estern, a Brooklynite sculptor, hated the pedestal JFK was put on from the very beginning. By the time the granite pedestal was done in 2003, Mr. Estern’s old JFK was no good. Based on a Smithsonian Institution survey, graffiti stained so deep that scrubbing them off had worn away the inscriptions which has the famous saying: “Ask not what your country can do for you as what you can do for your country.” The bust itself looked like it had been whacked by a bat. Instead of having a new one cast, Estern saw some places sculpture could improve. Now his work is complete and all the city has to do to put JFK on the plinth is to find a $70,000. Will that happen in 2009? — Urban Art and Antiques

(It was finally reinstalled in August 2010)

Page completed February 24, 2010

2 comments

President John F. Kennedy is there now.

Small error in Lincoln’s description-here he is on a horse see in multiple locations:

https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMRN0H_Young_Abe_Lincoln_on_Horseback_Syracuse_University_NY

http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/art/horse.htm

https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/wm13RXR_On_the_Circuit_Bethel_CT