As I mentioned at on FNY’s Midwood slice, “southeastern Brooklyn reveals an unbroken grid of unrelenting monotony.” Still, between about 1968 (when I first jumped on a bike and began exploring Brooklyn from my Bay Ridge home) and 1993, when I moved to fab Flushing, it was MY unbroken grid, and I fully employed it to bike from Bay Ridge to Canarsie, Ozone Park, Valley Stream, or any area that was more or less a straight line east of my home. I forayed to northern Brooklyn, too — Williamsburg, Bushwick, and Greenpoint were vastly different beasts than they are now — but I was most familiar with Marine Park, Midwood, East Flatbush, mainly because they happened to be on my route.

From 1978-1981 I worked in the Brooklyn Business Library, stacking books, arranging magazines, cleaning tables. (Your webmaster’s limited skill sets have kept me working at menial tasks at my different workplaces ever since, but I occasionally write ad catalogs and direct mail). Consequently I got a look at their full collection, one of which was a flaking, yellowing copy of the Belcher-Hyde Brooklyn desk atlas, produced in 1929. The Holy Grail! 1929 was a time when the modern Brooklyn street grid was being finally built on, especially in southern districts where development had been moribund, even in the Roaring Twenties. That meant that many of Brooklyn’s original colonial-era roads were still in place, even as development was displacing them. I thrilled to see the dirt tracks I had glimpsed on my bike rides through areas like East Flatbush, Midwood and Canarsie shown on the atlas with names inscribed in black and white on the printed page.

Years later, I got a look at a near-mint collection of the desk atlas at collector Brian Merlis‘ house, where he undoubtedly keeps it under lock and key. But now, anyone can get a glimpse at it, by purchasing a subscription to Historic Map Works. I’m not shilling for them but their material has been a great assistance to Forgotten NY. Just saying.

In late March 2010 I made my way out to East Flatbush for once of the few times since I moved away from Brooklyn in 1993, to seek out some ancient tracks and a very special building …

GOOGLE MAP: Forgotten NY East Flatbush

Getting to East Flatbush can be done by Subway, provided you want to do some walking. I took the #2 Seventh Avenue line from Penn Station south all the way to the Beverl(e)y Road station, which leaves you at Beverley and Nostrand (which takes the place of East 30th Street down here). After taking a look at some attached homes that were built no later than 1915 or so…

I noticed that Brooklyn’s greatest spelling debate since the “h” was expunged from Williamsburg is still raging, as we have two different spellings of Beverl(e)y at one cross street.

I have street maps that spell it two ways, one for each of Beverl(e)y’s two divisions east and west of Holy Cross Cemetery.

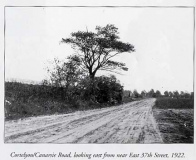

I walked a block south to Cortelyou Road and walked east. The road forms the southern boundary of Holy Cross Cemetery, which when consecrated in 1849 was the first Roman Catholic burying ground in Brooklyn other than the yard at St. James Church (now St. James Cathedral) on Jay Street downtown. The land was acquired by the St. James pastor from private owners in 1849 and over the next couple of decades, after additional land was purchased, the cemetery attained its present-day boundaries of roughly Brooklyn Avenue, Snyder Avenue and just south of it, Schenectady Avenue and Cortelyou Road. The image on the right is taken from Brian Merlis and Lee Rosenzweig’s comprehensive East Flatbush book, available at Brian’s website. Both scenes show Cortelyou Road and East 37th Street.

Interred in Holy Cross you will encounter mobster “Tough Tony” Anastasio, famed gourmand “Diamond Jim” Brady, NYC mayor William Grace, Brooklyn Dodger/NY Met Gil Hodges, ecclesiastical architect Patrick Keely, The Godfather actor Lenny “Luca Brazi” Montana, and Willie Sutton, who apocryphally said he robbed banks because “that’s where the money is.”

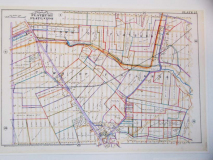

Canarsie Lane

Cortelyou Road was built using the roadbed of Canarsie Lane or Road, which was laid out just after 1800 as a connector from Old Flatbush Road (now Flatbush Avenue) a short distance south of the Dutch Reformed Church (at Cow Lane, now Church Avenue) to the village of Canarsie. In Historic Map Works I located an 1890 Kings County atlas showing the course of Canarsie Lane — since it’s divided at inconvenient areas, I crudely Photoshopped the pieces together.

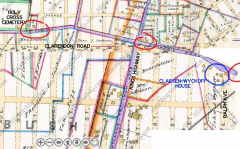

Other than the stretch forming the southern boundary of Holy Cross Cemetery, precious few pieces of this old road remain. I circled in red those that do: a short stretch from Schenectady Avenue and East 48th Street (left), a piece at Kings Highway (center) and another piece between Ralph Avenue and East 83rd (right).

An overzealous homeowner has ruined one of the neat brick attached houses that line side streets in East Flatbush by the hundreds, at Cortelyou and East 37th. RIGHT: Albany Avenue is one of series of avenues named for major NY State cities that run from Bedford-Stuyvesant south to East Flatbush. For all you non-New York City residents, right on red is usually verboten in the city except at marked locations like this.

A short piece of old Canarsie Lane runs between Schenectady Avenue and East 48th Street. It has been demapped by the city, and thus is pockmarked, potholed, and has not been paved in years.

The corner of East 48th once bore a street sign — I wonder if the Department of Transportation called this Canarsie Lane or Cortelyou Road?

I ambled east on Clarendon Road, a block south of Cortelyou. (In East Flatbush, Avenue B was replaced by Beverl(e)y Road, Avenue C by Clarendon, there is actually an Avenue D, Avenue E is Foster Avenue, Avenue F is Farragut Road, and Avenue G is Glenwood. Things are pretty much alphabetical south of that.

Soon enough, Clarendon has a major intersection at Utica Avenue, which replaces East 50th Street. Utica is a city of about 60,000 in Oneida County, about dead center on the map of New York State; it was named for an ancient Carthaginian city and is the hometown of Annette Funicello.

The city hasn’t updated its website for a while:

Central New York’s largest winter festival is set to host more than 2,000 participants Saturday, February 7th, 2004 at the Val Bialas Recreation Area.

I trust it was a blast.

In Brooklyn, Utica Avenue was the proposed trunk line of a southern Brooklyn IND Second System subway line in the 1930s. Depression and war happened, and the line was never built. After Utica Avenue gets out of Crown Heights running south, what you see here is pretty much what you get with the road — industry, car repair, mechanic shops dominate all the way south to Flatbush Avenue near Kings Plaza.

A rare non-attached house on Clarendon Road near East 52nd. Construction here really took off after World War II, so this is an older rarity.

Above right: a small piece of old Canarsie Lane is delineated on East 53rd by a slanting driveway. Construction is enjoined on the old highway, which is used here and there as private driveways.

Left: an extant slice of Canarsie Lane runs between East 54th and Kings Highway.

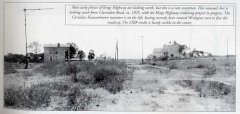

The intersection of Kings Highway and Clarendon Road is extraordinarily busy, and was also in 1909 for wagons and horsecarts, even when the intersection was then Flatlands Neck Road and Canarsie Lane. (looking south in 2010, north in 1909, but you get the idea). Image from Merlis and Rosenzweig’s East Flatbush, above link.

Left: In 1925, looking south on KIngs Highway from what would be Clarendon Road. The Corvington lamps will be illuminating Kings Highway after it is widened into the multilane behemoth we know and love today.

Though Kings Highway is very old — the British laid it out from Fulton Ferry south and southwest to Bay Ridge in 1709 — this is not an original section of it. East of Flatbush Avenue, when Kings Highway was widened, Flatlands Neck Road was included in the upgrade. The dirt road originally connected with the now-vanished Hunterfly Road in what is now Brownsville. Merlis and Rosenzweig

The truly massive Tilden High School, seen from Beverl(e)y Road and East 59th Street. The high school and nearby Tilden Avenue are named for NY State Governor (in 1875-76) Samuel Tilden, a Democrat yet a Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed opponent. In 1876 he won the Democratic nomination for President, won the popular vote vs. Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, but lost in the Electoral College, in an election similar to the one in 2000.

Tilden’s house at 15 Gramercy Park still stands and a statue of Tilden, dedicated in 1926, can be found at Riverside Drive and West 112th Street.

After you cross Ralph Avenue from Beverl(e)y Road, Avenue B finally turns up, as it runs for a few blocks from Ralph Avenue northeast to East 98th Street, along with Avenue A, in a neighborhood called Remsen Village on maps, though I’ve never hear the name in conversation or on news reports. We’re in the place where East Flatbush gradually evolves into Brownsville. There is an Avenue B in every borough except the Bronx, which has a B Street.

Though Avenues A and B are in ‘Remsen Village,’ Avenue C is miles away, in Kensington. The reasons for this lie in 19th-Century developer’s proclivities to assign British-sounding names to formerly “lettered”avenues: hence, Avenue A in Kensington and Flatbush became Albemarle Road, Avenue B became “Beverl(e)y” and so on. In Kensington, there are avenues that didn’t join in the renaming, like Avenues C and F, and there’s nothing left of Avenue G, which became Glenwood Road its entire length.

Ralph Avenue has two distinct sections, in Bedford-Stuyvesant and Brownsville, and cut off by a piece of the Canarsie street grid that extends NW to East New York Avenue through the old Brooklyn neighborhood called Pigtown (named for the pig farms that were located there), it resumes again at Remsen Avenue and runs south to Mill Basin near Kings Plaza.

Between Avenue B and Ditmas Avenue east of Ralph Avenue there is a tiny enclave of three small streets, Coventry Road and Branton and Dorset Streets, that aren’t a part of the overall grid of lettered avenues and numbered streets …they are lined with peak-roofed, well-kept attached brick buildings and are likely part of a single development. The trio of streets appear on maps as early as the late 1930s, but I imagine they were fully developed after World War II.

Ditmas Avenue facing Branton and Dorset Streets. I was always fascinated by these huge brick buildings on Ditmas, by far the most massive structures in the area. They stand between Ditmas Avenue and the NY Atlantic/LIRR Bay Ridge Branch tracks. They are currently in use by National Grid (the power company formerly Keyspan and before that, Brooklyn Union Gas). Ditmas and Ditmars are names found on Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island maps; Jan Jansen von Ditmarsum settled in western Long Island in the late 1600s.

Speaking of Dutch settlers, one such settler’s house is still standing nearby…

Pieter Claesen-Wyckoff House

Those living in East Flatbush in the late 1960s, and early 1970s, would never mistake this well-kept country house for the broken-down shack that it used to be. During its darkest days, though, the seeds were sowed for the revival of what is agreed by many scholars to be the oldest house in NY State, as the Pieter Claesen-Wyckoff House gained recognition for its lengthy history by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, established in 1965.

Pieter Claesen Wyckoff (1625-1694) arrived in America in 1637, before there was even a New Netherland. He was a 12-year-old illiterate indentured servant who worked for the patroon Kiliaen Van Rensselaer near Albany, until his servitude expired in 1644. By 1652, he was living in New Amersfoort (Flatlands) and became a supervisor on a farm belonging to Peter Stuyvesant, governor of New Netherlands, acquired some property, and became a town magistrate. In time, he was New Amersfoort’s wealthiest citizen. He built this house along the now-defunct Canarsie Lane in 1652; at the time it was situated on one of the higher hills in town, later leveled. When the British took over in 1664 the house became the property of the Duke of York, but later reverted to the Wyckoff family, which occupied it into the 20th century.

The Pieter Claesen-Wyckoff House along the course of old Canarsie Lane.

A divided Dutch door; the side part of the house is the oldest section.

Roof timbers, floorboards, and bedroom hearth. For the most part the roof timbers and floorboards are the originals. Decades’ worth of layers of paint had to be scraped off to reveal the wood beneath.

The kitchen, the building’s oldest section, has a low, heat retaining roof. By 1750 an east wing had been added, and the central hall was built by 1820, when the building attained its current appearance. The building’s artifacts include a document affirming Wyckoff’s allegiance to the King of England (sincerity unclear), a 17th-century pistol, and a hand-sewn initialed stocking worn in the 19th century by Pieter’s descendant, Cornelius Waldron Wyckoff.

By the mid-1970s, the house was in poor repair, its restoration beyond the means of the Wyckoff family. Fortunately, federal funds were allocated, and between 1979 and 1982, the architectural firm John Milner Associates restored the house to approximate its appearance in 1820 when it was last renovated, coping with a 1981 fire. Today, the Wyckoff House is thriving as a museum and community center. A vintage barn will be added to the property in 2010.

Visitors are quite welcome: call (718) 629-5400 for hours or check out the website.

In classic Brooklyn fashion, New York State’s oldest house is ensconced in a maze of car washes, junkyards, and flat fix shops that line Clarendon Road and Ditmas Avenue. I wouldn’t have it any other way!

For several decades the Colonial Gas station and Garage occupied the front lawn between the house and Clarendon Road, so that the Wyckoff house was virtually invisible from Clarendon. At right is a pice of the 1929 Belcher Hyde desk atlas, showing the house (the yellow square) along the now-demapped Canarsie Lane.

When I first encountered the Wyckoff house in the late 1970s and 1980s, Canarsie Lane still existed in this area and ran in front of the house.

The Pieter Claesen – Wyckoff House is one of 14 Dutch farmhouses still extant in Brooklyn, all of which were built between 1652 and 1825.

ForgottenFan Kevin O’Malley points out that the Old House in Cutchogue, Suffolk County, may be older.

A small piece of old Canarsie Lane, this one marked by a street sign, runs between Ralph Avenue and East 83rd across from the Wyckoff House.

The town map I sampled above on this page hangs in the foyer of the Wyckoff House. The house is on the map, but in the extreme upper right corner. Note that Paerdegat Basin once extended far into the area, as Paerdegat Creek, and formed the zigzag boundary between the towns of Flatbush and Flatlands. The name comes from two Dutch words meaning “horse” and “gate.” Property lines formed the main boundaries during this time.

Moving on past the junkyards of Ditmas Avenue and turning north on East 57th, we find Nazareth Regional High School. A frequent opponent of my Cathedral Prep high school sports teams, Nazareth’s first graduating class was in 1966 and the school became co-ed in 1976. NBA player and coach Mike Dunleavy Senior is a graduate; his Number 44 jersey is retired at Nazareth. (St John’s University and Golden State Warriors star Chris Mullin was an East Flatbush resident.)

I stumbled onto Kings Highway and meandered south for several blocks. The multi-lane section, which runs from Avenue P and Ocean Avenue northeast to Brownsville, still boasts several interesting items for lamppost freaks, like this single-arm bigloop Deskey. I’d imagine the other arm broke off some time ago. There are also some Twin double-mast octagonal poles, now becoming a rarity around town. RIGHT: which house is unlike the others?

LEFT: Name That Language, Glenwood Road and East 43rd Street. BY all accounts, Haitian Creole.

As I inched my way west again, the housing stock became more varied and hence, more interesting. This peaked, gabled house can be found at the NE corner of Avenue I and East 39th, catercorner to Amersfort Park. A sign near the front door is marked “Hubbard House, Est. 1896.” The Hubbard name is an old one in southern Brooklyn.

When biking in the area in the 1970s and 1980s I would use Avenue I frequently, and it now has a bike route, marked by a pavement stripe and green signs.

Amersfort Park, bordered by East 38th and 39th Streets and Avenues I and J, is a pleasant surprise if you’re passing through. It is atypical of NYC neighborhood parks in that there are no athletic fields or even jungle jims or swings — it’s just a pleasant green space with lawns, paths and benches. A former name for Flatlands is “New Amersfort” and the rock is a copy of a 200,000-year old rock found in Amersfoort, Holland.

The nickname for Amersfoort, Keistad (stone-city), originates in the Amersfoortse Kei, a boulder that was dragged into the city in 1661 by 400 people because of a bet. This story embarrassed the inhabitants, and they buried the boulder in the city, but after it was found again in 1903 it was placed on a prominent spot as a monument. All Experts

I haven’t the time to track down the Amersfoort rock in Google Earth, but you’re welcome to give it a shot. And, if any Dutch ForgottenFans can pinpoint it for me in Amersfoort, let me know. The town is a province of Utrecht, from whence many colonial-era Dutch settlers hailed.

Amersfort Park and its fountain on the Avenue J end.

Continuing west on Avenue I, between East 34th and 35th is one of the most beautiful attached mult-family homes in Brooklyn, from a time when they knew how to build these things. Bay fronts (some with surviving crenellation) , arched windows, cornices — these have it all.

This is akin to a Caligulan architectural orgy.(Figuratively). Original crenellation, iron gates, the light brown brick I admire (probably not Kreischer, though) and original wrought-iron gates. I hope the people living here appreciate what they have, and I hope the apartments are well-maintained on the inside.

ForgottenFan Erin Joslyn: The Victorian houses in East Flatbush (including those pictured around Amesfort Park) are all that remains of the first Victorian development in Flatbush – Vanderveer Park, which was begun in the 1892 and was developed in five phases. It was financed by the Germania Rail Co. and predated Prospect Park South, which is often referred to as the first such community in Flatbush. At the turn of the century, Vanderveer Park was significantly larger than all of the surviving Victorian Flatbush enclaves. The isolated Victorians around Sears in Flatbush were also part of Vanderveer Park.

Vanderveer Park was a development sponsored by Henry A. Meyer’s Germania Real Estate Company, which in 1893 purchased acreage from the Vanderveer Farm. At the time there was talk of a Flatbush annexation to Brooklyn (which happened in 1894) and Meyer set about covering newly-cut streets with ornate Victorian-era buildings. The name Vanderveer Park survives in the Vanderveer Park United Methodist Church at Glenwood Road near East 31st Street. And, there had been a Germania Place, connecting Campus Road and Flatbush Avenue north of Avenue H at Brooklyn College, but in 1959 it was changed to honor the nearby Brooklyn College Hillel building, named for the first century AD Jewish religious philosopher.

After a walk of approximately 5 miles it was time to get the #2 train at The Junction, the gateway to Brooklyn College at Flatbush and Nostrand Avenues and Avenue H, the IRT’s furthest southward plunge, back to Penn Station and the LIRR for lovely Little Neck.

Page photographed March 27, 2010

your webmaster Kevin Walsh: erpietri@earthlink.net

©2010 FNY