Broadway runs north from Bowling Green and, under a variety of names, runs north in NY State almost all the way to the Canadian border. Other than a few other aboriginal roads such as the Bowery and St. Nicholas Avenue, it is one of the very few roads that predated the colonial era that is still in use on Manhattan Island; it was used by the Lenape Indians before the Dutch arrived, and was probably in use by the buffalo before the Native Americans arrived. It is “broad” in a physical sense only when you get north of Columbus Circle — it’s of average width south of that, and called Broadway (Brede-weg) only because it was wide in comparison to the narrow cart paths of New Amsterdam that were laid out when the area was first colonized in the 1620s.

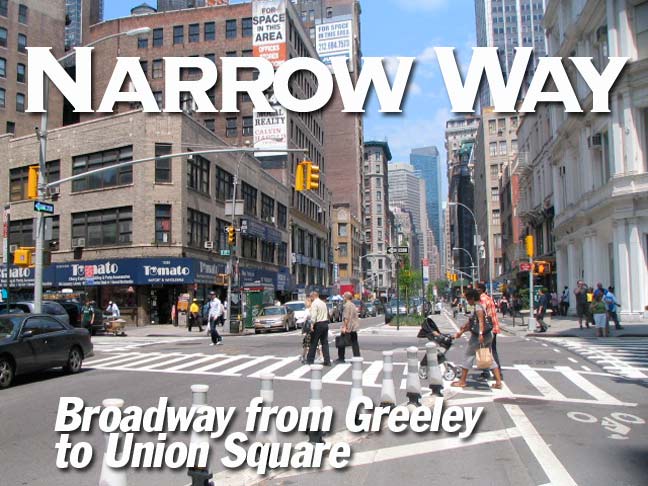

I recently took the FNY Canon PowerShot S1-IS down Broadway from Greeley Square, where Broadway, 6th Avenue and West 32nd Street come together, to Union Square, named for the places where Broadway and the Eastern Post Road to Boston came together in the colonial era.

I was familiar with this stretch of the World’s Greatest Street since I have worked in the area on two occasions: from mid-1988 to late 1991, I was a proofreader and a typesetter at a shop called ANY Phototype, named after the initials of the three Russian immigrants who founded it, and from 2000-2004 I was a copywriter in the Home Goods department for Macy’s, composing incredibly repetitive flyer and newspaper blurbs for mattresses, kitchen implements, bath towels and textiles. I received a thorough knowledge of the location of Macy’s wood escalators, and occasionally escaped onto the roof ledge for some photo ops, before being dragged back in and lectured and threatened by the management. (Actually the ledge was quite accessible before 9/11/01.) The management lectured and threatened me for other reasons.

ANY Phototype, meanwhile, was a very strange existence — in a company of about 15 employees, I was one of four native English speakers. I was at this type shop just before the era of computer typesetting — we worked at green screen terminals and had to type in extremely complicated lines of code to get things like accent marks to print. And there were a lot of accent marks, because ANY Phototype took work in “any” language that used Roman characters, as well as Russian-language publications that used Cyrillic letters. I didn’t work on the latter, but had to work with every other language. Since I speak only English (some say I am still learning that one) I had to work character by character. There was none of the instinctive feel that you have when working in your own language — studies say the human eye and brain only require the first and last letters of a word to apply proper context and make sense of written communication. I worked with languages I have never seen before or since, such as Haitian Creole and Romansch, a language spoken by 35,000 people in Switzerland.

I was at ANY long before conceiving of Forgotten New York but, when the weather was decent, I would instinctively explore the midtown and nearby Chelsea areas and file away objects of interest in my head. In those days I lived in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn and would use the R local to get to work, getting out and in at the 28th Street station (in the early 1990s deferred maintenance had left the Manhattan Bridge mostly useless for express trains on my routes). I occasionally would walk down the old Tin Pan Alley row to work.

The Broadway I found there, the wholesaling capital of Manhattan with sidewalks clogged with hawkers and knockoffs of leather goods, costume jewelry, and cheap clothes — was grimy, gritty and sweaty in the summer, and that’s really the only way to experience it — visit during the dog days between Memorial Day and Labor Day, let the perspiration trickle down your neck and enjoy the ambience of a true NYC experience. And, using this humble page as a guide, look up occasionally and view the fantastical architecture, which will never be replicated anywhere again.

Hotel McAlpin, Broadway and West 33rd Street, constructed in 1913; when built, its 1500 rooms made it NYC’s largest. The lounge was hung with expensive tapestries and the dining room decorated with gold; its Marine Grill was appointed with glazed terra cotta tiles by artist Frederick Dana Marsh.

The McAlpin’s Marine Grill featured terra cotta depictions of large ocean liners like the Mauretania and Commonwealth as well as the steamboat Clermont, in brilliant color, shown above right. They can be found today in a passageway connecting the various lines in what will be the Fulton Street Transit Center downtown. Incredibly, they were about to be trashed after the restaurant closed and were almost in a Dumpster when the Arts For Transit program rescued them! The building is now known as the Herald Towers and contains luxury apartments.

At West 32nd, Henry Hardenburgh’s Hotel Martinique had preceded the McAlpin by a decade or so when it rose in 1900 and expanded greatly in 1910. Its own restaurant was modeled after the Apollo Room of the Louvre featuring Walnut panels and wainscoting and panels depicting Louis XIV and his courtiers. The hotel was not named for the Caribbean island but for its original owner, William R. H. Martin. (R.H. were popular initials around here — Rowland Hussey Macy’s giant emporium moved to Herald square in 1902.) After a stint as a homeless shelter, the Martinique was revived as part of the Radisson chain.

Across the street we find the old Gimbels Department Store, built from 1908-1912 by architect Daniel Burnham. It was reborn as the glassed-in, hollowed-out Manhattan Mall in 1989. When I worked in the area from 1988-1991 I would often get lunch on the 7th floor Food Court, which had large windows facing Greeley Square and the Hotels McAlpin and Martinique. In the late 1990s, though, the building’s owners decided that executives deserved these views more than the rabbling public; lunching shoppers were banished to the basement, while the 7th floor was converted to offices.

Just as Broadway’s intersection with 7th Avenue makes a ‘bow tie’ on the map as Times Square, it also makes a ‘bow tie’ effect with 6th, with Herald Square the top half at West 35th and Greeley Square the bottom, at West 32nd. Both are actually triangles, not squares. Honored here is Horace Greeley, founder of the New York Tribune newspaper.

An advocate of social reform (Karl Marx was a European correspondent), Greeley supported abolition, worker’s rights and Western settlement. As a reporter covering Congress in 1855, he was given a concussion by the cane of pro-slavery House Speaker Albert Rust. He helped found the Republican Party and was instrumental in making Abraham Lincoln the 1860 candidate. Surprisingly, he was the 1872 Democratic candidate for president; he was trounced by U.S. Grant and died a month later. NY Songlines

Alexander Doyle’s 1894 statue of Horace Greeley here was commissioned by the Typographical Society of America: Greeley was first president of Typographical Union No. 6. There is another statue of Greeley downtown, on the east end of City Hall Park facing the Municipal Building. That one, by John Quincy Adams Ward, was produced in 1890.

Abraham Lincoln’s letter to Horace Greeley

“We ended up at the Grand Hotel,” say Deep Purple in Smoke On The Water, referring to the Montreux, Switzerland Grand Hotel. There was one in NYC, as well, at the SE corner of Broadway and West 30th Street, constructed in 1868. Its mansard roof and prominent pediments are now [2010] obscured by construction netting. Right: 1255 Broadway at West 31st, the 1909 Dempsey Building. Below left: From 1964-1985 Manhattan had yellow and black street signs, with blue and white ones in the Bronx; for unknown reasons, blue and white signs have shown up here.

Broadway’s wholesale district reaches a crescendo at West 29th Street, and signs of every color advertsing costume jewelry, electronics, perfume, and cell phones proliferate.

1205 Broadway at the NW corner of West 29th is plain except for a concrete knob plopped seemingly at random at the top.

Even the light posts get into the act, festooned with signs from top to bottom.

The SE corner of 1186 Broadway and West 29th is held down by what was the Hotel Breslin when it opened in 1903 on the site of the Sturtevant House Hotel (1871-1902). It is now the Ace, still a hotel.

From 1875 to 1895 Broadway in this stretch was NYC’s vice capital: gambling dens, music halls, prostitution, ‘wild revelry and uproarious scenes.’ It was known as the Tenderloin district because cops on the take there were heard to say they could now eat tenderloin instead of chuck steak. There were respectable places here amid all the hugger-mugger, such as the original Delmonico’s at Broadway and West 26th. Banvard’s Museum, showing sculptures, paintings, caged animals and birds, and a tableau vivant featuring live models and actors depicting scenes from Dante’s Inferno. (The fun parts, I hope.)

For kicks these days, well, there’s Shepard Fairey, of the Obey Giant and Hope Obama artwork, who installed large works all over lower Manhattan in May 2010. Some were promptly defaced by rival street artists and graffiti taggers, but this one survived intact. Fairey’s stuff reminds me of Communist propaganda stylings (note, stylings; I don’t think he’s a strict propagandist, though the Hope poster was).

Signs, signs, signs of every size and color can be seen on Broadway on the diaginal strip between Greeley and Madison Squares. This is Manhattan’s great wholesale district where handbags, clothing items, costume jewelry and electronics can be purchased by both bargain hunters and store owners who will sell them retail.

Many Broadway buildings on the west side facing south are blunt-edged so that the view is directly south on the thoroughfare. This technique is known as chamfering.

Broadway has become the Narrow Way for much of its length from Times Square south to Madison Square, as the Department of Transportation has closed off a lane and built a bicycle-dedicated lane, complete with barrier. On this particular Sunday, I counted about three cyclists using it. At one point I wanted to cross at a green (not in between) but had to pause so a cyclist could run a light, as I almost always have to do in such a circumstance.

As an occasional bicyclist I have had to watch out for doorers for over 3 decades, and while the new dedicated lanes cut that risk down greatly, I’m somewhat amused by the new deference the DOT has for bicyclists, most of whom flout traffic regulations. Where was the DOT when I was on a bicycle more regularly than I am now, from 1968-2005? Well, there’s been a lot of noise and heat put on the city by the bike lobby (Streetsblog and Transportation Alternatives, which I quit about 20 years ago when I perceived, correctly, that they were using cycling toward a greater anti-automobile agenda. I never ride a bike as a political or environmental protest against the evil auto.)

It’s all sort of strange.

Every day when reporting to work at 130 West 29th Street (a grimy place, built between the wars and still there) I could look down the street and see the magnificent, mountainous Gilsey Hotel at 1200 Broadway. It goes all the way back to 1869 and was designed by stephen DecaturHatch and Daniel D. Badger (which is a great name). When I was working in the area in the late 1980s it was painted deep brown, but it was later restored to the cream color it was reputed to have had when it first went up. It was the first hotel to offer telephone service to guests. It had a bar made of silver dollars. Playwright Oscar Wilde and Diamond Jim Brady, the great gourmand, were frequent guests.

My zoom comes in handy for this kind of thing. The Gilsey clock (which naturally isn’t upkept) is supported by a pair of caryatids and a head beneath. Below right: It just looksm like the Gilsey has an antenna here, as the King Of all Buildings is sneaking up behind. By 1911 the Gilsey closed down and the many rooms were occupied by garment trade lofts.

I would sometimes have lunch at a long-gone German restaurant that occupied one of the storefronts on the West 29th Street side. Anyone remember the name?

ForgottenFan John Leifert: It was called “The Olde Garden”, and it was a truly wonderful place. I had at least 4 of 5 terrific seafood dinners there in the early 80s. Very atmospheric, with a great feel of Old New York City, and now gone. I think it turned into a Chinese restaurant.

Broadway and West 29th, southwest corner: No. 1203, the Wallach Building. I can imagine a Howard Roark building something like this, before rejecting the Deco approach as too rigidly doctrinaire for the new kind of architecture he wanted to create. It was built in 1929 by real-life architect Louis Shampan.

The AIA Guide to NYC describes the Baudouine Building, at the SW corner of West 28th Street and 1181-1183 Broadway, as “a sliver with a temple on top.” The 11-story building has the date of construction, 1895, emblazoned on the Greek-styled, Ionic columned temple at the apex. RIGHT: The 13-story Johnston Building at the SE corner dates to 1903 and is known for the corner domed turret, just a little higher than the temple across the street, and its carved lion heads. I’d love a chance to get into both of them!

1161-1175 Broadway at the NW corner of 27th is one of my favorite buildings in this stretch — it’s relatively low-rise in a stretch of goliaths. Of course like most buildings I like, it is suffocated by sidewalk scaffolding. It was the Coleman House Hotel when it was first constructed in 1907.

The multicolor brick St. James Building on the SW corner of West 26th Street and 1133 Broadway dates to 1897 and is marked by its 3-story arcade along the roofline. The corner features prominent stone quoining on the corner. The large circular window above the front door is called an oculus, after the Latin for “eye.” Daniel Burnham, who built the Fuller (Flatiron) Building 3 blocks south, assisted in the design. It replaced the earlier St. James Hotel, which Confederate terrorists attempted to burn down in 1864.

Townsend Building, NW corner of West 25th Street and Broadway. was finished in 1896 and designed by Cyrus Eidlitz. Note once again the corner chamfering.

The complicated intersection of Broadway, 5th Avenue and West 23d-25th Streets allows for some much-needed wide open spaces — Broadway can be quite claustrophobe-enducing in its diagonal stretch between Greeley and Union Squares. Tall towers take advantage of this space:

The General William Jenkins Worth Monument was the first such tower, built to honor the War of 1812, Indian Wars and Mexican War fighter. After his 1849 death the general was buried in Brooklyn, and re-buried here after this obelisk was constructed in 1857. Therefore, this is tied as the smallest cemetery in NYC with the Amiable Child Monument near Grant’s Tomb. Fort Worth, Texas also honors him.

For many years the 1903 Fuller (Flatiron) Building and the 1909 Metropolitan Life Building dominated the Madison Square skies, but they were joined by two tall residential towers in the early 1980s and again in the mid-2000s.

A jumper? Not quite — this is an art installation by British artist Anthony Gormley, who has placed several naked male sculptures in the Madison Square vicinity in an art installation called Event Horizon. The statues will be in place until August 15, 2010.

“I don’t know what is going to happen, what it will look and feel like, but I want to play with the city and people’s perceptions. My intention is to get the sculptures as close to the edge of the buildings as possible. The field of the installation should have no defining boundary. The gaze is the principle dynamic of the work; the idea of looking and finding, or looking and seeking, and in the process perhaps re-assessing your own position in the world. So in encountering these peripheral things, perhaps one becomes aware of one’s status of embedment.” Event Horizon site

I liked the Cow Parade in 2000 and Christo’s Central Park orange shower curtains in 2005 better. I might not know much about art, but I know what I like.

As for a more lasting example of public art, here’s the Fifth Avenue Building sidewalk clock, which went up along with the 1909 office building, the International Toy Center, was constructed. In 1957’s Sweet Smell of Success, the vicious Broadway columnist J. J. Hunsecker, played by Burt Lancaster, had his office here.

One of the most ornate of New York’s castiron street clocks, it is composed of a rectangular, classically ornamented base and fluted Ionic column with Scammozzi capital. The two dials, marked by Roman numerals, are framed by wreaths of leaves and crowned by a cartouche. The gilded cast-iron masterpiece was manufactured by the Hecla Iron works. — From the 1981 NYCLPC Landmark Designation Report

One of two cast and wrought iron Twinlamps dating back to 1910-1915 at the Broadway-5th Avenue-West 23rd Street intersection. This is one of the few such examples in town whose 1940s-era Bell luminaires have been outfitted with bright sodium vapor bulbs.

Just as Macy’s moved uptown from its original location, so did Lord & Taylor. The store’s 3rd location was in this French Second Empire building, on the southwest corner of 901 Broadway and East 20th Street. L&T was here from 1873-1914 in one of NYC’s larger cast iron front buildings. British immigrant Samuel Lord and George Washington Taylor established their first dry goods store on Catherine Slip on the Lower East Side in 1826.

The Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace, or the building constructed in 1923 to look exactly like it, a National Historic Site, can be found at 28 East 20th Street, just east of Broadway. The Women’s Roosevelt Memorial Association purchased the property in 1919 and rebuilt the house, stocking it with items owned by Roosevelt’s sisters and wife. There’s a comprehensive history of Roosevelt’s early life, his exploits with the Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War and as New York State Governor, and his “trust-busting” and peacemaking efforts (he was the first President, of 4 so far, to win the Nobel Peace Prize).

McKim, Mead and White were known for larger, more elaborate buildings, but the architects built the compact Warren Building at 905-907 Broadway at the NW corner of East 20th. The building is festooned with ornamentation as was the wont in 1897, and chamfered corners, of course. Also, of course, sidewalk scaffolds.

More scaffolds to greet you at the NW corner of Broadway and East 18th, where the Hoyt Building at 873-879 forms a greater facade with the Arnold, Constable & Co. department store building. Each was built between 1868 and 1872. Arnold, Constable was founded by Aaron Arnold and son-in-law James Constable and developed a fierce rivalry with Lord & Taylor — even moving uptown when Lord & Taylor did, in 1914. Its final locale was at 5th Avenue and East 40th in the building occupied by the Mid-Manhattan Library, where your webmaster has given some well-attended slide shows. ABC Carpet occupies buildings on either side of Broadway now.

Paragon Sporting Goods, which has been around since 1908, holds down the ground floor of the 1883 red brick Ditson Building at the SW corner of 18th and 867-869 Broadway. In the long past, it has housed the Ditson sheet music store and the Whiting Silver Manufacturing Company.

The tallest building between Madison and Union Squares is the 11-story McIntyre Building at #874 and the NE corner of East 18th, by architect Robert H. Robertson. When the Cobra Club was here in the 1970s, snakes used to escape and slither all over the place, says NYC Songlines.

Likely the oldest building on this stretch at #857 faces Union Square across East 17th. It was built in 1848, though renovated in 1884, and has recently gotten an ugly paint job. It is known as the Robert Goelet House (no, not this guy).More Broadway coming soon! This is far from a comprehensive look — for that, see NYC Songlines as well as David Dunlap’s On Broadway (Rizzoli) at old book websites like alibris and a better library near you.

5/23/10