I stumbled desultorily through the lost neighborhood of a vanished youth, a broken man with broken teeth. When I visit Bay Ridge these days it is mostly to visit my dentist, and work has been endless this year, with two cracked incisors, a crown falling out, an impacted wisdom tooth, and other work too gruesome to detail here. My tenuous health obviously the consequences of an overly starchy diet through the decades, I was literally getting my just desserts; humans are meant to eat green plants, which are tasteless. Numbed by Novocaine, I squinted through the almost painful autumnal sun that was nearly enough to blind your aged and addled webmaster, and at length, I found myself wobbling past a street sign that inspired this FNY webpage: Gatling Place.

Fort Hamilton is the crown jewel of Bay Ridge, an active fort on the southwest tip of Long Island since it was completed in 1831. It is situated on the Narrows, a strait separating Long Island and Staten Island, and a strategic point for any enemy vessels that would attempt to enter Upper New York Bay and then the island of Manhattan from the south. In the Revolutionary War, British troops invaded Long Island in August 1776 by landing on property near the future fort owned by a Denyse Denyse. Patriots fired on the British warship Asia during the invasion, but it was of little hindrance.

It might be odd to hear that Robert E. Lee, the great general of the Confederacy, was once a major figure in Brooklyn. While still a captain in the US Army in 1839, Lee was given the task of improving armament at Fort Hamilton as well as other forts in the region, and served here until 1846. A major east-west street inside the military reservation is named for him, and he was a vestryman at St. John’s Episcopal (Anglican) Church at Fort Hamilton Parkway and 99th Street. The church is still there, now on its second structure.

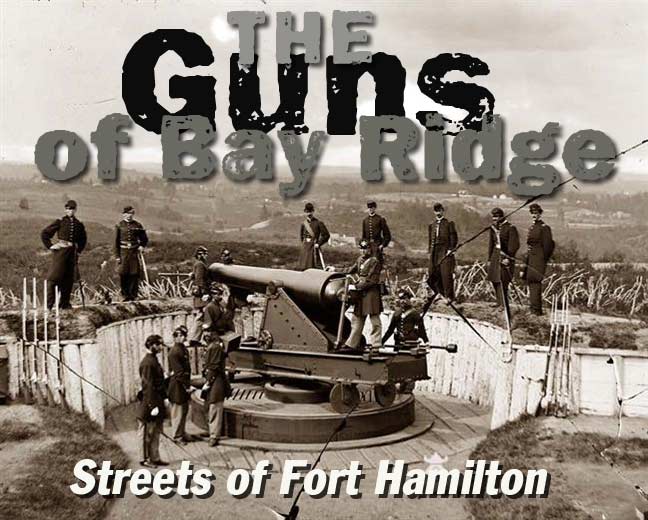

Fort Hamilton defended the United States during the Civil War, a conflict that Lee’s conscience led to join the other side. During the war, great advances in military technology were made, a frequent consequence of war. A series of short streets north of the fort in Bay Ridge were named for a trio of military engineers who vastly improved US armament. I decided to walk these streets, and record some observations. I’ll also provide some information on the weapons that are name checked here.

There was a time, fifty years ago, when Gatling and Dahlgren Places did not face the Gowanus Expressway, and so had a full compliment of homes and street trees on either side. The multifamily on the right is likely among Gatling Place’s earliest surviving buildings, though some smaller ones we’ll see later may be older. The PC Richard & Son is the place where I may have purchased a TV set that was appropriated by neighborhood youth for community use. Or it may not have been; there’ve been a number of them.

Despite what the Google Map says, Gatling Place does not extend north of 86th Street.

Gatling

Continuing on Gatling Place, I spotted what appeared to be a 3rd-generation Chevrolet van (produced after 1971), but if anyone can ascertain the exact year let me know. The Chevy van was first rolled off the production line in 1964, and models continued to be made until 1996; the Chevrolet Express succeeded the van that year. Its greatest pop culture moments came from its use in the A-Team TV show and Sammy Johns’ Top Five hit from early 1975.

The owner is obviously a soccer and baseball fan, as Italian soccer star Roberto Baggio and Mets legend Tom Seaver are mentioned on the back of the van.

Nearing 88th Street I spotted the rear of what appears to be a 1965 or 1966 Mercury Park Lane Breezaway. It had an unusual retrograde back window that could roll down.

The attached houses here likely date back to the 1940s or 1950s, as basement garages began to be popular in the postwar period.

It’s frequently the case, but by no means automatic, that the smallest houses on the block are the oldest, so 130 Gatling, above, could hold that title. Above left: 74 Gatling is the biggest apartment house facing Gatling Place — many of the apartment buildings on the block are the back ends of the ones facing Ft. Hamilton Parkway, a block to the west.

As is de rigeuer, 2000-2010 architectural sensibilities, i.e. junk, are also becoming a presence here with generic multifamily dwellings that could have come off a production line have appeared recently.

You might expect house numbers here to be in the 8600s and up, since we’re south of 86th Street, but unlike parallel avenues, such as Fort Hamilton Parkway and 4th, 5th, 7th Avenues, the numbering of these short streets begins at one at 86th Street.

Gatling Place ends at 92nd Street, but continues as a ramp onto the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Straight ahead is the ramp to the lower level, while bearing left goes to the upper level. As a rule, I cross the bridge on a bus, which almost always uses the lower level.

As mentioned earlier, 50 years ago both Gatling Place and its opposite member across the expressway, Dahlgren Place, were sleepy tree-lined streets. There must have been quite the hue and cry when plans were drawn up to put entrance and exit ramps on them, and assure they would not be so sleepy anymore. In the 1950s, though, NYC roads czar Robert Moses almost always got his way. More about Moses can be found in Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, and an account of the building of the bridge in the context of those affected most by its construction, in Gay Talese’s The Bridge.

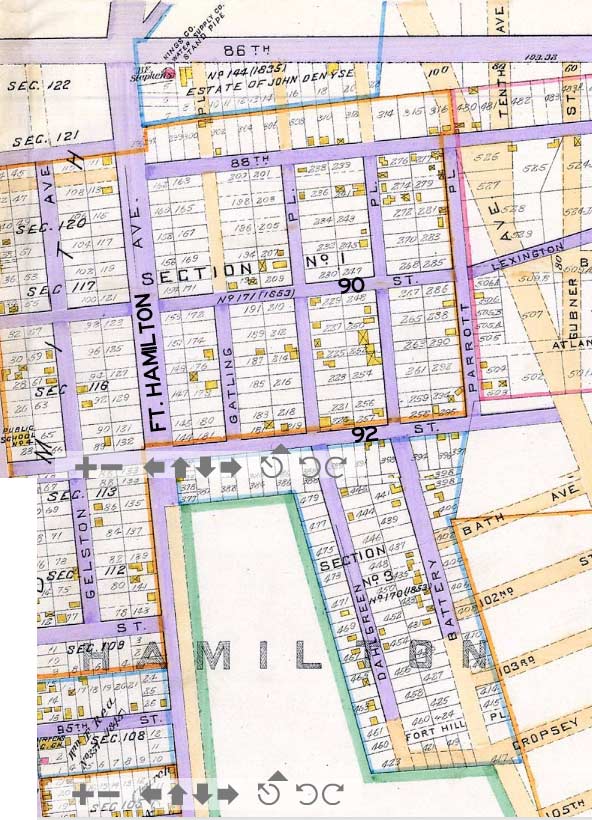

This map, produced by E. Robinson, shows the neighborhood as it was on the map in 1890. At the time, this was still part of the Town of New Utrecht, whhich would become part of the City of Brooklyn in 1894, and in turn, annexed by the City of New York in 1898.

What impresses you most are what is still there over a century later. On the map legend, it simply states that streets shown in purple are open, those in beige not open. While few buildings then existed — they are shown by small yellow squares in the building plots — the streets explored on this page had been already opened.

A spelling error on one of the streets shown on this map persisted through much of the 20th Century. I will reveal it in the next section.

Some parts of this map, such as the Bath Avenue, 102nd, 103rd, Cropsey etc on the lower right edge, which has been replaced by Poly Prep, and the Lexington Avenue and Gubner Street, on the right side, which has been replaced by the Dyker Park Golf Course, are no longer there and I’m not sure they ever existed — they may have been in existence on maps only, reflecting the plans of developers.

Crossing the expressway at 92nd Street to Dahlgren Place, I spotted one of the decent brick residences constructed in mid-century. Even though there’s a garage in the basement, its impact is lessened by some green space in front and a second floor terrace.

Congressman Ron Paul of Texas was a Republican candidate for President in 2008 and 2012, eventually losing in the primaries to John McCain and Mitt Romney, respectively; he had previously run in 1988 as the nominee of the Libertarian Party. His 2008 candidacy seems to have paved the way for his son, ophthalmologist Rand Paul, who won the 2010 Senate race in Kentucky.

The Gowanus Expressway is designated Interstate Highway 278. I-278 runs from Route 1/Route 9 in Linden, NJ to the Bruckner Interchange in the Bronx, where it meets the Cross Bronx Expressway (I-295) and the Hutchinson River Parkway, and encompasses the Union Freeway, Staten Island Expressway, Gowanus Expressway, Brooklyn-Queens Expressway Grand Central Parkway, Triborough (RFK) Bridge, and Bruckner Expressway. Its first designated route was in 1958.

Dahlgren

Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren (1809-1870) was a naval ordnance innovator and commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. Dahlgren became a midshipman in 1826. Service on the U.S. Coast Survey (1834-37) distinguished his early career. In 1847, Lieutenant Dahlgren was assigned to ordnance duty at the Washington Navy Yard. Over the next fifteen years, he invented and developed bronze boat guns, heavy smoothbore shell guns, and rifled ordnance. He also created the first sustained weapons R&D program and organization in U.S. naval history. For these achievements, Dahlgren became known as the “father of American naval ordnance.” His heavy smoothbores, characterized by their unusual bottle shape, were derived from scientific research in ballistics and metallurgy, manufactured and tested under the most comprehensive program of quality control in the Navy to that time, and were the Navy’s standard shipboard armament during the Civil War. Promoted to commander in 1855, captain in 1862, and rear admiral in 1863, he became commandant of the Washington Navy Yard in 1861 and chief of the Bureau of Ordnance in 1862.

With help from his friend Abraham Lincoln, Dahlgren took command of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron in July 1863, and for the next two years led naval forces besieging Charleston in the Union navy’s most frustrating campaign. Dahlgren cooperated magnificently with Army forces, but underhanded machinations by the ground force commander hindered the effort. Dahlgren’s courage remained beyond question during naval attacks on enemy fortifications, but he never figured out how to counter the enemy’s underwater defenses. As a leader, he took good care of his enlisted men, but failed to inspire his officers. After the war he commanded respectively the South Pacific Squadron, the Bureau of Ordnance, and the Washington Navy Yard. Navy History and Heritage

The admiral was born in Philadelphia; his son, Col. Ulric Dahlgren, was killed in a cavalry raid while on a mission to assassinate Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The admiral’s younger brother, Brigadier General Charles Dahlgren, fought on the Confederate side.

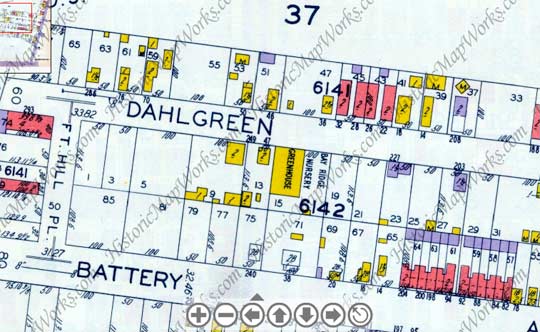

For much of the 20th Century, mapmakers and even then-NYC Department of Traffic, on street signs, persisted in spelling Admiral Dahlgren’s name incorrectly, with an extra E. When new signs appeared when the Gowanus Expressway was completed in 1964, the spelling error was finally corrected. Above: Belcher-Hyde atlas, 1929

It’ll soon cost you $15 to drive past Dahlgren Place’s modest houses. Most of you, anyway. Both Verrazano Bridge exit ramps direct truck, bus, and car traffic onto Dahlgren’s formerly moribund route. In photo above, the top deck ramp is on the right, the bottom deck on the left. I had thought the Department of Transportation ran the Verrazano and other NYCbridges, but the Metropolitan Transit Authority has control of this green space next to the ramp and reminds dog owners not to make a mess of the place.

Though Dahlgren Place comes to a dead end at a brick wall that marks the boundary with Fort Hamilton, it does have an outlet in tiny Fort Hill Place. There was never a Fort Hill in the area, though there had been a Fort Lafayette (originally Fort Diamond) situated in the Narrows outside Fort Hamilton from 1812-1959; it was demolished to make room for the Brooklyn tower of the Verrazano Bridge. Fort Lafayette (and Fort Hamilton) is remembered by two dead end lanes on 94th Street between 3rd and 4th Avenues, Hamilton and Lafayette Walks.

Fort Hill Place was likely named because it is situated on a slight rise seen most clearly by traveling south on Battery Avenue. The one-block street connects Battery Avenue and Dahlgren Place. It’s one of Bay Ridge’s least traveled streets, and I had only been there a couple of times in 35 years in the neighborhood. So, I was unaware that there’s a clear view of the wedding cake-white clock tower of Poly Prep Country Day School, located on 7th Avenue south of 92nd street. The clock tower is a well-known Bay Ridge landmark, visible from as much as 20 blocks away. The school was founded in 1854 in downtown Brooklyn; it purchased 25 acres of land from the Dyker Beach Golf Course and built a new school here in 1916.

Battery Avenue

On maps Battery Avenue is shown running from 86th Street south to Poly Place, and it still does, though the southernmost few hundred feet are in Fort Hamilton, and so the road comes to an effective dead end after it makes an unusual S curve south of Fort Hill Place. The fort annexed Battery Avenue and Poly Place sometime in the 1970s.

Battery Avenue used to be longer than that, extending south to the Narrows (at least on maps), but by 1929 it had been truncated to its present length.

Some Battery Avenue homes, on the lengthy block between Fort Hill Place and 92nd Street.

The former Victory Memorial Hospital Building, 7th Avenue and 92nd Street. The hospital closed in early 2008 after a 107-year history; the Bay Ridge area has two other hospitals, Lutheran Medical on 2nd Avenue and 55th Street and Maimonides Hospital (I was born there) on 10th Avenue and 48th. Victory Memorial is now State University of New York Downstate Medical Center of Bay Ridge, a research center and medical school.

As a kid I found it hard to suppress a chuckle when I wandered over to Parrott Place. Of course, the name has nothing to do with squawking birds. As a kid, I knew where the neighborhood’s ‘haunted houses’ were — one was on Ft. Hamilton Parkway and 88th and another on Parrott just north of 92nd. Of course, both of them were torn down years before I could bring a camera over. Here are a pair of distinctive Parrott Place houses.

Parrott

Robert Parker Parrott (1804-1877) was born in New Hampshire, graduating with honors from West Point in 1824; he remained there as an instructor until 1829. In 1836, he joined the West Point Iron and Cannon Foundry in Cold Spring, New York, remaining there the rest of his life. He produced a series of the Parrott rifle, shown above, in 1860. The cannon’s largest models weighed 13 tons and could fire shot weighing as much as 300 pounds; 10-pound Parrott guns were used most extensively by both the Union and Confederate sides in the Civil War.

Robert Parker Parrott (1804-1877) was born in New Hampshire, graduating with honors from West Point in 1824; he remained there as an instructor until 1829. In 1836, he joined the West Point Iron and Cannon Foundry in Cold Spring, New York, remaining there the rest of his life. He produced a series of the Parrott rifle, shown above, in 1860. The cannon’s largest models weighed 13 tons and could fire shot weighing as much as 300 pounds; 10-pound Parrott guns were used most extensively by both the Union and Confederate sides in the Civil War.

The breaching power of the 10-inch 300-pounder Parrott rifled gun, now about to be used against the brick walls of Fort Sumter, will best be understood by comparing it with the ordinary 24-pounder siege gun, which was the largest gun used for breaching during the Italian War.

The 24-pounder round shot, which starts with a velocity of 1,625 feet per second, strikes an object at the distance of 3,500 yards, with a velocity of about 300 feet per second. The 10-in rifle 300-pound shot has an initial velocity of 1,111 feet, and has afterward a remaining velocity of 700 feet per second, at a distance of 3,500 yards.

From well-known mechanical laws, the resistance which these projectiles are capable of overcoming is equal to 33,750 pounds and 1,914,150 pounds, raised one foot in a second respectively. Making allowances for the differences of the diameters of these projectiles, it will be found that their penetrating power will be 1 to 19.6. The penetration of the 24-pounder shot at 3,500 yards, in brick work, is 6.2 inches. The penetration of the 10-inch projectile will therefore be between six and seven feet into the same material.

To use a more familiar illustration, the power of the 10-in rifle shot at the distance of 3,500 yards, may be said to be equal to the united blows of 200 sledge hammers weighing 100 pounds each, falling from a height of ten feet and acting upon a drill ten inches in diameter. –Washington Republican, August 12, 1863

When I’m in the area, I’m always drawn like a magnet to the Kenruby Apartments, 90th Street just east of Dahlgren. It’s a wild Tudor with great detailing like stucco, black and white checkerboard lineleum and even a small shelf both sides of the entrance to put a planter.

Between 88th and 90th Parrott Place is lined with these attached 2-family houses, all with arched doorways (a similar batch of these is on Narrows Avenue, several blocks away). Right: this small house marks the 7th Avenue/Parrott Place boundary. It’s officially on 7th Avenue because it has an 86– address.

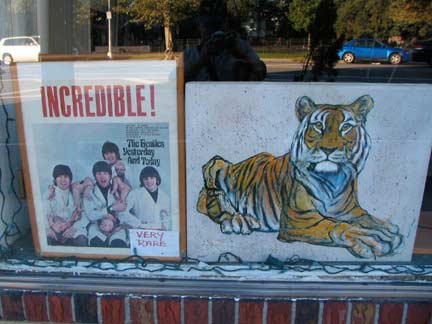

#6 Parrott Place, the first address on the street, is home to a beauty parlor and an art instruction school. What is apparently an original Beatles Butcher Cover is displayed in the window. When Capitol Records wanted to release a Beatles greatest hits (and songs left off other Capitol releases) collection in 1966, Yesterday and Today, the original cover featured the Fab Four in lab coats, butchered meat, blood, and severed doll parts. The photo had been taken by Robert Walker as part of a conceptual art piece called “Somnambulant Adventure.” The photo was originally used in promo adverts for the 1966 single “Paperback Writer” and on the cover of the June 11th, 1966 edition of Disc music magazine.

Approximately 750,000 Yesterday and Today LPs were printed using the “butcher cover” but were only for sale in some stores for one day. After many agitated complaints from dealers, the LPs were recalled and Capitol pasted a picture of the Beatles and a steamer trunk, and rereleased the albums with the altered covers. The “butcher covers” that were never pasted over with the steamer trunk picture command the highest collector prices.

Accounts have it that Paul McCartney pushed for the bizarre cover in response to the Vietnam War, one of the few times Paul’s publicity skills deserted him. It would have been disastrous, as this was around the time John Lennon was in hot water about his remark that Christianity would “vanish and shrink.” Thus went one of the more bizarre Beatles episodes in their career.

And thus ends FNY’s Guns of Bay Ridge page.

10/31/10