Though NYC divested itself of most of its colonial-era “royal” names after defeating the British in the Revolutionary War, there are a few that doggedly hang on, sich as Prince Street in Soho, Kings Highway in Brooklyn, and Fort Tryon Park in upper Manhattan, which was named for British fort commemorating Sir William Tryon (1729-1788) , the last British governor of the colonies before the scurvy rebels kicked them out. The city took title to the property, which was in part owned by the former Cornelius Billings estate, in 1917, and the large (67 acres) park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (son of the Central and Prospect Park developer) in 1935. There’s a good deal of highlights for even the most avowed non-naturalist such as your webmaster to enjoy here.

Fort Tryon Park is one of the two great parks of upper Manhattan island, the other being Inwood Hill Park (which still has caves where Native Americans resided, Manhattan’s last forest, and the spot where, according to many accounts, Peter Minuet “purchased” the island from the Lenape (since the Lenape did not follow the concept of personal property to be bought and sold, they were unaware they were even selling the land).

I reached Fort Tryon Park via Broadway and about Ellwood Street, and if you have ever climbed the steps and hills from Broadway up to the park promontory, you will agree with me that if you could do those steps every day, you’d quickly be back in fighting form. Unfortunately I don’t have the opportunity every day, and I both work and live on first floors.

In season, there’s plenty to fancy plant, tree and bird lovers, but I am more of a masonry fan, and in Fort Tryon I found much to pique interest, including some Billings-era remnants.

Central isn’t the only park in town with some nifty rustic shelters and masonry arches. Upon ascending the steps I huffed an puffed my way into the Gazebo, which overlooks Sir William (as in Tryon)’s Dog Run. There are a series of arches in the western end of the park carring pedestrian paths under Margaret Corbin Drive, named for a woman who ‘manned’ a cannon after her husband was shot during a battle in the war for independence — one of the USA’s first female combatants.

On a somewhat hazy day the New Jersey Palisades, created by Hudson River erosion over thousands of years, are visible. To the north, The Cloisters, a branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art specializing in medieval art and assembled by John D. Rockefeller Junior in 1938, looms over Fort Tryon Park.

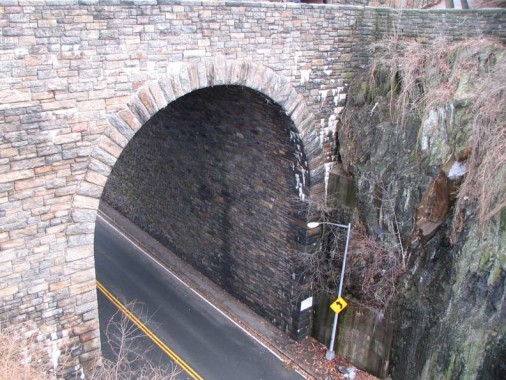

What is likely one of the highest arched masonry bridges in NYC — only High Bridge itself might be taller — takes one loop of Margaret Corbin Drive over the other. This gives you an idea of high the hills are here.

One of the most interesting aspects of Fort Tryon Park is that this plaque commemorating American troops and Margaret Corbin was erected by Cornelius Billings in 1909 when this was still part of his estate. The plaque is immense and must weigh the considerable part of a ton.

There is a full-service restaurant, the New Leaf Cafe, within Fort Tryon Park. The ivied arches lead to Linden Terrace, the park’s highest point, giving views of eastern Manhattan and the Bronx beyond that.

This secluded architectural gem, sorely in need of renovation, was discovered by [New York Restoration Project] Founder Bette Midler as she and her friends undertook their clean-up and restoration of Fort Tryon Park in 1995. In 2001, NYRP was able to assume management of the establishment — formerly operated as a New York City Parks concession — and within a few short years, transformed the New Leaf into an acclaimed fine-dining destination. NYRP