It’s not surprising, to me at least, that while the Brutalist, unadorned lamppost designs of the 1970s and 1980s are increasingly falling out of favor, their more ornate, scrolled cast iron cousins of the 1910s through 1940s have been slowly coming back to prominence. NYC first began to install new versions of the classic Bishop Crook in the 1980s, and one by one, more of NYC’s classic lamppost designs have been reproduced and found new homes. At the same time, new designs have also come to the fore, most notably in downtown Brooklyn, where Fulton Street has been given a set of ultramodern (to some eyes, dystopian) light poles.

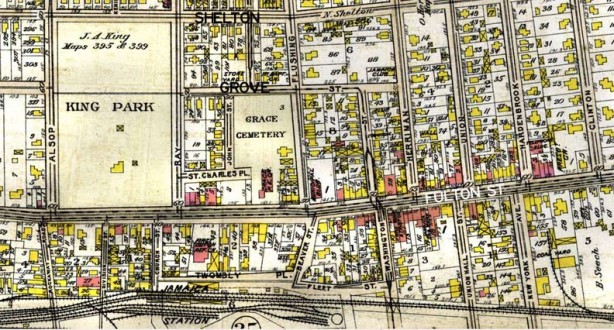

Before I get into the lamppost replacement du jour along the title road of Jamaica, Queens, here’s a map of the downtown area of that neighborhood in 1909. While many of the historic landmarks along the Jamaica Plank Road, since remnamed Fulton Street and then Jamaica Avenue, are still intact including Rufus King’s mansion, Grace Church, and Prospect Cemetery (all subjects of a ForgottenTour in 2012) not one street name has been retained, with the exception of Union Hall Street on the right side of the map. Queens streets were mostly given numbers beginning in 1915 and proceeding gradually over the next couple of decades — Queens street signs carried two names for several years, with the new name or number on top and the old name in smaller type on the bottom.

And, even major roads not receiving numbers got new names, such as Trotting Course Lane becoming Woodhaven Boulevard and the Jackson Avenue/Broadway combo uniting under the Northern Boulevard moniker. NYC officials have never grown tired of renaming Queens roads — in the 1960s, North Hempstead Turnpike became the (admittedly less confusing) Booth Memorial Avenue, recognizing both a hospital and the founder of the Salvation Army; while the rather straightforward New York Avenue and later New York Boulevard was named for a local Jamaica politician, Guy Brewer, in 1982. It’s rare that a wholesale renaming takes place these days, however; a movement to rename Brooklyn’s Fulton Street after Underground Railroad heroine Harriet Ross Tubman has resulted in only some new signs being affixed under the Fulton Street signs.

Today, though, I’m here to talk about the changes in street lighting that have occurred along Jamaica Avenue. I’ve witnessed a couple of changes of the guard over the past couple of decades.

Between 1917 and 1977, a span of 60 years, an elevated train rumbled over downtown Jamaica. In 1977, changes occurred to the line when it was decided to eliminate several eastern stops: Metropolitan Avenue, Queens Boulevard, Sutphin Boulevard, 160th Street, and 168th Street. In the 1960s, plans drawn up for subway expansion included a grand plan to build a line through southeast Queens that would use part of the Long Island Rail Road right of way and necessitate a new tunnel under Archer Avenue.

Financial problems, as well as the usual inertia when it comes to building mass transit, meant the shelving of that plan, but the Archer Avenue tunnel was fairly well along and it was decided to use it to replace the lost el of Jamaica Avenue, and thus a few new stations at Kew Gardens (serving the IND Queens Blvd. line), Sutphin Boulevard (that became a LIRR and later, AirTrain connection) and Parsons Boulevard/Archer Avenue were built. The Queens Boulevard line was also extended into the tunnel, making a heretofore unavailable direct connection from the E to the J trains available.

Above is a photo from the 1930s showing Jamaica Avenue at about 162nd Street. On the left is the J. Kurtz and Sons department store, whose building remains in place. On the right, the F.W. Woolworth convenience store chain, with its distinctive red and gold signs, survived into the 1990s.

Street lighting here is fairly straightforward. As the el was not very high off the ground here, pendant lights have been added underneath it. Before the el, gaslights lit the Jamaica Plank Road and Fulton Street. In the 1960s, “Dwarf” lampposts were positioned on sidewalks under the el.

After service ended east of 120th Street on the Jamaica el (even though the Archer Avenue tunnel wouldn’t open for business until December 1988) the city began to remove it, but they did so gradually; it took about three years to get rid of the pillars, and the last Dwarf post wasn’t removed until 1999 or 2000. [photo: Facebook, Long Island and NYC Places that are no more] In this photo, the trestle supporting an el station has been temporarily left in place.

You can also tell the state of the city’s finances by the rust on the lampposts. In the late 1970s, there was no money to effect repairs to infrastructure and the city began to fall apart. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that the city’s lampposts began to get regular silver paint jobs again.

Removing the Jamaica el was supposed to bring business back and revitalize the neighborhood. But such a revival was delayed by several years as subway service was absent for eleven years. [photo: Facebook, Long Island and NYC Places that are no more]

By 1980 the last of the elevated train pillars were coming down. This one, in Bicentennial red, white and blue livery, was needed as a temporary stanchion for stoplights and pedestrian control signals in the heart of Jamaica at Jamaica Avenue and Parsons Boulevard. In the 1990s this corner would see the construction of the Joseph P. Addabbo Federal Building and a large retail/movie theater combo across the street from the photo.

There may have been more of them, but by the time I arrived in Queens in 1993, this was the last of the “Dwarf” lampposts that populated Jamaica Avenue under the el, at the Van Wyck Expressway. It was a block away from Jamaica’s last bowling alley that disappeared around 2000. This lamp didn’t make it past 1999 or so.

With the el stanchions gone at long last, in the 1980s the city made “improvements” by installing these streamlined streetlamp/stoplight/DONTWALK posts between about Sutphin Blvd. and 169th Street (fill me in if the streets are wrong). They were ultramodern, modular, and soulless. They could carry the streetlamp alone, or the streetlamp and the stoplight, or all three, depending on what was needed. The city also installed new sidewalks and 2-colored street crossings, some of which are still there.

The boxy nature of these posts necessitated installing a different genus of “one-way” sign on them instead of the standard black and white one-way sign seen elsewhere around town.

One of the more fascinating aspects of these poles was that the street signs– in the early 1980s they were Queens white with blue letters — fitted snugly on the shaft, and there they remained for over thirty years, surviving the Great Street Sign Purge of the post-1985 years in which NYC’s color-coded street signs were all replaced by green and whites. In fact, these white signs were such nonentities that the Department of Transportation didn’t even bother to remove them and just installed green signs right next to them!

At 161st and Jamaica, a modular post carrying several traffic signs stands next to a decommissioned White Castle.

Coming of the Tribes

But in 2011, another purge took place and the modular posts — some of which were rusting badly– were torn down in favor of the retro-Triborough posts that had also recently appeared on Broadway and Ditmars Boulevard in Long Island City.

While the Broadway and Ditmars Tribes sported black paint jobs and shielded teardrop luminaires, here on Jamaica Avenue they’re gray (as they are on the Triborough) and are fitted with Stad luminaires.

I do question their contextual use here — they do make sense in Astoria, since that area is close to the Triborough, but Jamaica has little to do with the Triborough and plenty of other designs, such as the ultramodern Brooklyn Fulton Street lamps, were available.

On Union Hall Street (which commemorates a former school) we see a set of shorter Tribe posts.

As with all recent new and retro streetlamp designs, the Department of Transportation commissioned versions that can be fitted easily on top of already existing guy-wired stoplight stanchions. At 153rd Street, King Manor Park and the former First Reformed Church of Jamaica (now a performing arts center) stand catercorner from each other.

Jam. Parsons

On the four corners of Parsons Boulevard and Jamaica Avenue, you will find, at least in early 2013, the final four surviving modular posts. They’re exhibiting quite a bit of rust, while the post on the southwest corner is the only one still retaining its original luminaire. I’d imagine the DOT has something special in mind for this corner, and these poles are marking time until anything new is ready.

When they’re gone…will this species of lamppost be gone?

Not quite: Avenue D in East Flatbush, between Albany and Schenectady Avenues, has a set of very similar models on selected corners. In fact, there are short versions of the poles not seen in Jamaica. These also have white street signs that the DOT apparently doesn’t know about. I’m not sure if these are going away any time soon…

…and, 181st Street has a set, as well.

2/3/13