I haven’t done as many long-form specials with as many as 100 pictures per page of late. In the Age of Twitter, people are increasingly impatient with these long treatises and tend to lose interest. Also, the winter winds play havoc with my tear ducts and I frequently have tears streaking down my face when walking outdoors from November to April, and though my state of mind usually runs between neutral and mildly irritated, I never make a show of expressing displeasure so blatantly.

Today, though, I was insufficiently ambitious to tackle the new (well, only 4 years old, but I haven’t been there in awhile) new pedestrian path that runs through Latourette Park in Staten Island, connecting old Richmondtown with the Staten Island Mall area. I will get there eventually if I can climb out of bed early enough. Instead I wanted to see what’s happening on the Bowery lately — I tend to walk its length every few years, perhaps subconsciously calling upon the ghosts of the bums and transients of yore to look amenably upon my trespasses and make my lifelong unlucky streak turn for the better. That, and I wanted to see how much of the old Bowery has held up to the assaults of modernity. I got out of the F train at East Broadway and meandered back up to Penn Station, snapping away at whatever interested me. Hopefully, it will interest you.

WAYFARING MAP: Seward Park to Penn Station

Straus Square is an overlooked little triangle formed by Rutgers Street, Canal Street and East Broadway. Here, two streets are generated: Canal, which roars west to the Hudson River, and Essex, which runs north to East Houston, where it becomes Avenue A. It was named for Jewish philanthopist Nathan Straus (1848-1931), a partner with his brother Isidor in the giant Macy’s department store early in the 20th Century, assisted and funded a program distributing pasteurized and sterilized milk to children countrywide. He also championed a Jewish state in Palestine, a cause he did not live to see.

Since Memorial Day 1953, Straus Square has been punctuated by a cylindrical monument featuring carven allegorical figures, a monument to area war dead from the two World Wars. After 60 years it’s the worse for wear and could stand a cleaning.

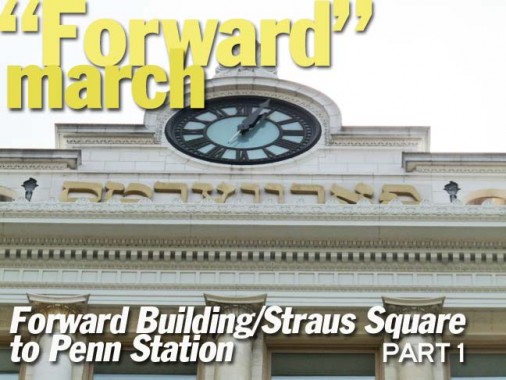

Facing Straus Square is the recently renovated (for expensive living spaces) Jewish Daily Forward Building. The word Forverts, or Forward, in Hebrew characters is spelled below the clock at the roofline. The building was designed in 1911 by architect George Boehn to house the offices of the influential then-daily founded by Abraham Cahan in 1897. It quickly became the most influential newspaper in the Jewish community and was an early example of advocacy journalism, fighting to eliminate sweatshops, supporting the labor movement and battling corrupt politicians. The Forward moved uptown years ago and the building then housed the Chinese Center and then became upscale living space.

For a complete history of the Forward and this building, see its NYC Landmarks Designation Report.

Likenesses of four prominent Jewish socialists appear above the front entrance: Karl Marx, Friedrich Adler, Ferdinand Lassalle and Friedrich Engels.

The square is also punctuated by William H. Seward Park, named for the US Senator from New York who served as Secretary of State in the Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson administrations. He engineered the purchase of Alaska from Russia and was wounded during Booth’s assassination of Lincoln at Washington’s Ford’s Theater when an associate of Booth tried to kill him as well. His statue in Madison Square is the oldest portrait statue remaining in NYC.

While other fountains around town have been refurbished and repaired (in the case of the Jacob Wrey Mould Fountain in City Hall Park, spectacularly so) the Jacob Schiff Fountain in Seward Park remains stubbornly ruined.

Schiff, a turn of the 20th Century Jewish financier and philanthropist, donated the fountain to what was then called Rutgers Square in 1894, employing architect Arnold W. Brunner. Schiff “donated the fountain to the City, asking not for recognition of the deed, but only that it ‘be kept in proper condition so that the people of the Seventh Ward may have an opportunity to enjoy it.’ Unfortunately the city has never been able to maintain it: reports on its deterioration surfaced as early as the 1930s. An inscription from the Bible’s Book of Exodus has nearly faded away:

“… and there shall come water out of it, that the people may drink.” — referencing the miracle in which Moses struck a rock with his staff, producing a fall of water.

Friends of Seward Park is attempting to “crowd fund” a restoration, which could take as much as $1 million.

In 1903 the Edison Company made a film of neighborhood kids horsing around in the fountain.

Across East Broadway from Straus Square is the 169 Bar, which conveniently has an attorney upstairs.

This place has been a Lower East Side institution for decades, and a drinking den under one name or another for nearly a century. Previously called the Bloody Bucket, this bar was frequented by bums who didn’t expect to eat where they drank. Nowadays 169 Bar offers a full food menu with raw bar offerings. Oysters on the half shell in a dive bar without proper locks on the bathrooms? You betcha.

But you’re not here for the oysters, and neither are you here for the house “specialty” cocktails, though we hear the Bloody Mary with pickled okra is solid. The main attractions at 169 are five dollar beer-and-any-shot combos, cheap highballs and humble bar fare … One Drink Ahead

The Seward Park Library, East Broadway east of the park, was constructed in 1910 as one of the libraries instituted by Scottish immigrant, industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie’s donations. It used to have the largest Yiddish language collections in NYC, and its holdings there are still numerous.

Canal Street “begins” at Straus Square, as its house numbers run east to west. One of the busiest east-west auto and truck routes in Manhattan, it connects the Manhattan Bridge with the Holland Tunnel; its incredible traffic volume made traffic czar Robert Moses make the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have covered Broome Street, on his list of priorities in the 1950s, until the idea was finally scotched by neighborhood groups.

Is it time to reconsider the LoMex as a tunnel?

One of NYC’s ancient street vents, probably dealing with exhaust from the Rutgers Street IND subway tunnel, can be found on Essex Street at Seward Park. This specimen resembles the Pangolin (I8U2-236a).

Unfortunately, Schames Paints at #3 Essex has moved to 90 Delancey Street and saw fit to not remove its colorful awning sign as well as the vintage Dutch Boy Paints sign, so unless this property remains unsold for awhile, these terrific signs will be going away soon.

Some parts of the Lower East Side look exactly as they must have in 1910 or 1920, if you can forget about the plywood over the windows and vinyl awning signs.

I have never spent a lot of time on Hester Street (or Canal, for that matter, since I hate all the traffic noise) and I had missed out on PS 42 at Ludlow, a temple of learning if there ever was one. It was built in 1898 by prolific schools architect C.B.J. Snyder. In 1916 it was co-named the Benjamin Altman School for a local philanthropist and art dealer who had died three years before.

Hester Street, decades ago, was the site of the Lower East Side’s biggest outdoor market or bazaar, other than Orchard Street, and was chockablock with pushcarts piled high with merchandise from the stores that lined the streets.

The NW corner of Hester and Ludlow features this old-school apartment building that has never been cleaned or repointed, but I feel a certain sense of NYC pride in this. The 2000s have seen NYC burnished to a gleam by developers and redevelopers, and this building has a sense of keeping it real. A modern building stands just to its east.

Here I’m showing the Allen Street median in two directions — the top, which looks so clean it resembles an artist’s rendering, is the new pedestrian path looking north, while the bottom picture shows it looking south, in keeping-it-real mode. Apparently the bike and pedestrian paths are being reconstructed in stages.

Until the Fantastic Forties, Allen Street was much narrower and the old 2nd Avenue el ran over it.

Hester Street east of Allen. Chinatown has grown bigger and bigger over the years and can now be said to extend completely over Little Italy’s old territory as far north as Kenmare/Delancey Streets.

At Eldridge Street and Hester we come to a rather ridiculous schools complex that dominates a complete block and eliminated part of Forsyth Street, consisting of three schools, each of which has its own huge bay, or curved protuberance.

This Street View scene of Hester at Eldridge gives you a fairly obvious illustration of the differences in esthetic philosophy between 1983 (left) and about 1900 (right).

The school housed here is called the Emma Lazarus School. Her sonnet honoring the Statue of Liberty was inscribed on a plaque placed on the statue’s granite pedestal in 1903. Though she passed by the statue on a ship while returning from Europe in 1887, a year after Liberty was dedicated, Lazarus (1849-1887) was too ill to actually see the “New Colossus” because of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which claimed her life at age 38.

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Also facing Hester at Forsyth is the Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Intermediate, or Junior, High School. Sun (1866-1925) was the founder and first president of the first Chinese republic, after the 1911 overthrow of the dynastic system that had ruled China for millennia.

The lengthy corridor park between Forsyth, Chrystie, Canal and East Houston Streets sees plenty of use in this otherwise park-starved part of town. It also has a rather impressive comfort station. It is named for Sara Delano Roosevelt, the mother of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Land between Chrystie and Forsyth Streets was acquired by the city, which planned to build low-cost housing, but built a corridor park instead and named it for Mrs. Roosevelt in 1934, two years after the ascension of her son to the White House.

I was hoping to catch a glimpse of the birdcage guys of Sara Roosevelt Park, but they set up further north, at Delancey.

I detoured a block to Chrystie and Grand. This stretch of Chrystie was home base to both the Beastie Boys and the New York Dolls, in different decades. I liked the old school signage of the Ocean Star Seafood Market, and we will see more.

A look south at Hester and Chrystie to the triumphal entrance arch of the Manhattan Bridge. Carrere and Hastings’ arch is based on the Porte St. Denis in Paris, and the colonnade on a similar one in St. Peter’s Square in Rome.

There have been many Boweries in the past, and there are many now. It is one of the oldest roads in NYC, a part of the old Boston Post Road that also encompasses Park Row downtown, part of St. Nicholas Avenue uptown, and a maze of streets in the northern Bronx. The Bowery led to Peter Stuyvesant’s farm, or bouwerie, in the 1600s; after NYC was built up north of City Hall it became an entertainment district; and after the el arrived it evolved into the place where NYC’s down-and-out congregated. Specialized wholesalers lined the route even after the el came down in 1955, and its new guise as a center for high-rise expensive condos with the New Museum as its vanguard happened after 2000.

On the Bowery and Hester is one of its centers of diamond and jewelry dealers, which dominate it from Canal to Hester, and a corner pharmacy with a Siamese twin attachment of a corner candy store.

When the 3rd Avenue El was built along the Bowery in 1878, it didn’t shadow it — at least, not at first. Steam engines traveled on two trestles on either side of the avenue. When the system was electrified after 1916, a regulation-style el was built, throwing it into shadow and speeding the progress of its skid row.

I’ve been on the Bowery before… I walked it in 2005 on this page I will be referencing. Many locales cited on that page no longer exist. In 2007 I returned and cited more of its secrets, some of which are now gone.

97 Bowery, north of Hester, is one of the avenue’s few cast iron front buildings. It was built in 1869 by architect Peter L.P. Tostevin and was occupied until 1935 by John P. Jube & Co., a hardware and carriage supply business. It was granted NYC Landmarks status in 2010.

The painted word “Coogan” seen facing south on the east side of the Bowery near Grand is the exact same one that can be seen in photos of the Bowery from the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. James J. Coogan operated a dry goods and/or furniture store here between Hester and Grand; 1888 photos show this painted sign in place even then, so it has survived close to 125 years. And yes, as Manhattan Past explains, there is a connection to Coogan’s Bluff uptown near the old Polo Grounds.

The Bowery is known for its aggregation of wholesale kitchen equipment dealers. There are Chinese-American dealers in the Grand Street area, and more a few blocks north.

A nice sign advertises a glassware wholesaler.

A pharmacy on the ground floor of the old Bowery Bank building sports signage in Vietnamese, which is written in Roman letters, but with plenty of accents. Some vowels have two accent marks.

McKim, Mead and White’s Bowery Savings Bank Building, at Grand Street, has been a majestic presence on the Bowery since 1894. Bowery Bank had stood in this location since 1834: this was the third building. It was the first Roman Classical style bank building in America. The interior featured marble mosaic floors, yellow marble tellers’ counters, and cast-iron skylights and stairs. Thankfully the building has been saved and is now the Capitale nightclub. The large characters on the exterior are an ad for a kindergarten. Some of the old interior can be seen at the Capitale website.

On the Bowery some of the oldest houses, in the Federal style, can be recognized by their dormer windows. These go back to the Civil War era and even earlier.

Here is one of the many interior lighting wholesalers that are concentrated in the Grand Street-Broome Street Bowery corridor. There are over a dozen in the area.

“We ended up at the Grand Hotel…” above one of the lighting shops.

Their shelves are filled with “tombstones” in different colors: orange, gold, copper, blue, black, silver. Tombstones are what bartenders call the tallish, slender machines that ring up beers and martinis and the occasional burger. The Faermans sell new electronic machines, too, but it is these old ones that are prized by restaurateurs who want that old-fashioned look behind the bar.

A walk down the aisle at their store is like a little archaeological expedition. The cash registers show the last total they rang up: 00.55 on that one, who knows how long ago; 50.76 on this one. That one over there still packs a mean stomach punch when the drawer flies open. NYTimes

Bowery Restaurant Supply at Delancey Street in the former Puritan Hotel.

The former Germania Bank, built in 1898 on Spring Street, looks abandoned, with the graffiti of decades accumulating on the outsides. The stone cladding has never been cleaned in recent memory. This is all with the tacit approval of photographer Jay Maisel and family, who own the whole building and have lived there since 1966.

”Every single thing that can come out of a human body has been left on my doorstep.” –Jay Maisel, whose building is estimated to be worth $50M these days.

Detouring east on Rivington, crowds gather outside Freeman Alley, which was just a sliver between a couple of buildings until a trendy restaurant was founded at the very end a few years ago. The Freeman’s Sporting Club, an upscale mishmosh of a haberdasher and barber, is on the corner.

More from the Bowery, 25th Street and 7th Avenue in Part 2!

Meanwhile read New York Songlines for much more on the Bowery.

4/15/13