I have an affinity for subways, trains and railroads… not at the “foamer” level, but I have enough knowledge to recognize model numbers on most NYC, Long Island Rail Road and Metro-North (formerly NY Central) cars, or “equipment” as the insiders say. I know where the old els were, and where closed sections of various subway and RR lines are. I know enough that “Rail Road” is two capitalized words with the LIRR and only the LIRR.

In the early 20th Century, various railroads ran steam lines through the then-hinterlands of Brooklyn: the Sea Beach Line, West End Line, the Brighton, Culver and Canarsie Lines. Most of them were eventually folded into Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit and in 1940, became part of the overall NYC subway system. By 1920 most of these lines became elevated railroads or ran in open cuts, where cross streets dead-ended or were ran across them in overpasses. One grade-cross, however, stubbornly held on until 1973, the East 105th Street station.

In the Bronx, my NY Central history is shamefully uncertain. I don’t know if the New York Central had any active grade crossings in the 20th Century. When the NY, Westchester and Boston was constructed in the early 1910s, its builders placed it in open cuts, tunnels and trestles to purposefully avoid grade crossings. In a fit of madness, I walked what is approximately the entire length of the NYW&B in 2012.

In Manhattan, various freights and passenger lines ran straight up Park and 11th Avenues, but the Park Avenue lines were in a trench while the 11th Avenue freights made every cross street a grade cross. The 11th Avenue freights moved slowly and were preceded with a man on horseback waving a flag, so mishaps were rare. The West Side Freight Railroad, today’s High Line Park, replaced the steam engines and cowboys. And after the present Grand Central Terminal was finished in 1913, Park Avenue rails were placed in a tunnel north to 97th Street, and on an elevated trestle north of that.

In Staten Island the what was then called Staten Island Rapid Transit eliminated most of its grade crossings by 1935. A few areas, such as trackage in New Dorp, held on to surface lines until the mid-1960s. As we’ll eventually see, though, there’s still a grade crossing or two in Richmond County.

GOOGLE MAP: ACTIVE NYC GRADE CROSSINGS

Queens is where most of NYC’s grade crossings are found, and surprisingly most of them are in western Queens, the borough’s most urbanified region…

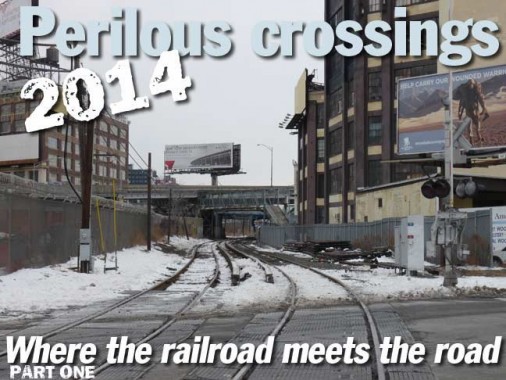

I began my survey on a January Saturday that saw snow develop before I completed the mission. I carried on intermittently and finished in August.

Dominie’s Hoek (Hook), originally the western end of the town of Newtown, was originally settled when a tract of land was awarded to Everard Bogardus, a Dutch Reformed minister (dominie), in 1643. The land was later owned by British sea captain George Hunter and by 1825 had become known as Hunter’s Point. It began the transition from rural farmland in the 1860s when the Long Island Rail Road built a terminal that would be its primary connection with Manhattan until the East River tunnels and Pennsylvania Station were built in 1910.

Between 1853 and 1861, substantial progress was made in creating the town of Hunter’s Point. Streets were laid out, buildings were erected, and a ferry service to Manhattan was begun. With ample available land, few existing residences, and excellent barge access via the East River and Newtown Creek, industries, eventually including railroad yards, oil and kerosene producers, and paint and varnish manufacturers, began to move to the Hunter’s Point area. New rail service on the Long Island Rail Road to Long Island City began in 1861.

The westernmost Queens grade crossing takes 11th Street across LIRR tracks leading to the LIC yard to a stub end used by several local businesses. A crossunder connects two sides of 11th Street that straddle the Pulaski Bridge, completed in September 1954 and named after Polish military commander and American Revolutionary War fighter Kazimierz (Casimir) Pułaski. As one side begins at 53rd Avenue, this is the only part that crosses the tracks.

At 11th Street there is actually a track junction. Looking east, the track on the left leads to the Hunters Point Avenue station and goes through Sunnyside Yards to the LIRR Main Branch. The track on the right goes to the so-called Montauk branch through Blissville, Maspeth and Glendale, connecting with Jamaica where it meets the Main Branch. Today it is used just for freight, but as late as two years ago it saw one or two daily passenger runs.

While the previous photo appears as if it could be Anywhere USA there’s no mistaking the spot when you point the camera west, as the King of All Buildings seems to loom largest from western Queens and also the NJ Meadowlands, where it seems to rise out of nowhere. The ESB will have more rivals than ever in the coming years, but like Elvis, it’ll still be the King.

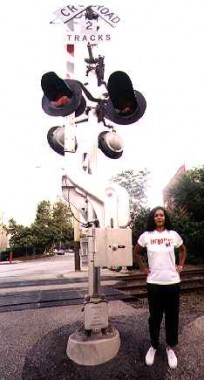

Railroad crossing signals and lights come in a variety of different configurations; in NYC, many of them are made by Western-Cullen-Hayes, which has a charming mid-1990s style website.

Here’s a history of the “crossbuck” RR crossing symbol. If you go back far enough when there were more grade crossings than now, they were marked by diamond-shaped signs.

This view looks north along 11th Street toward Borden Avenue. Note that the crossing gate indicates three tracks.

Here is likely the busiest grade crossing in Hunters Point. takes Hunters Point station-bound trains from the LIC yard over busy Borden Avenue, which is the direct link for vehicular traffic from Hunters Point to the Long Island Expressway. This old road first appears on maps in the mid-to-late 1800s and is named for an early area landowner, not the dairy conglomerate. Few streets in Queens have undergone quite as much of a transformation as Borden Avenue; photos from the early 20th Century show it as a suburban stretch lined with small shops and foliage. In the 1950s, though, the Queens-Midtown Expressway was bruited along its length, utterly transforming it to a service road. Here in Hunters Point, though, Borden Avenue still maintains something resembling autonomy.

What is a single track diverging from the Montauk tracks at 11th Street splits into an east- and westbound at Borden Avenue. This view looks back toward the Pulaski Bridge approach.

It’s unusual to see passenger trains and freights running over Borden Avenue, which can get pretty busy during the week, but several passenger trains en route from LIC to Jamaica do pass this way during mornings and evenings. I’m not sure how many freights use these tracks, barring hanging around for several hours during the week. As you can see this area is dotted with multi-floored warehouses and factory buildings that hold massive billboards, as advertisers attempt to gain the attention of motorists on the Queens Midtown Expressway.

Pressing east on Borden Avenue to seek the next grade crossing, I cannot help but note the many-windowed Blanchard Building, its U changed to a V by stonecarvers under orders to make the “U” the Roman “V” to impart majesty and permanency. It stands sentinel on Borden Avenue near 21st Street, the old Van Alst Avenue. Its upper floors look out on the noxious and noisome Newtown Creek. It’s one of the brick hulks around town that I ceaselessly admire, whether they are factories or warehouses (as almost all of them once were) or converted into residential apartments. In this part of Hunters Point, that fate is still largely unlikely, as the residential fever that has taken over the west side of the neighborhood near the East River hasn’t reached its business side. The Blanchard looks across the street at a Fresh Direct depot on Borden, one of the handful of main streets allowed to keep its name after many were given numbers in the early 20th Century.

In a former life the Blanchard was a factory that made fireproof doors and shutters. Some years after a fire started in the Columbia Paper Bag company engulfed it in flames, Blanchard rebuilt, only to merge with the John Rapp Company, becoming the United States Metal Products Company.

Today the Blanchard hosts many businesses and offices, with a deli on the bottom floor. Its type of brick construction is timeless.

The Dutch Kills, for which the neighborhood to its north is named, is generally so saturated with chemicals and leftover byproducts of God-knows-what activities that it won’t generally freeze, but today was so cold that there was a thin skin of ice on the surface. This shot looks south toward the railroad bridge that carries the LIRR Montauk Branch over it, and beyond that, #1 World Trade center in downtown Manhattan.

From one of my own recent favorite FNY pages, The Names of the Neighborhoods of Queens:

Dutch Kills, named for the Newtown Creek inlet, is concentrated near Queens Plaza and the west end of the massive Sunnyside railroad yards servicing Long Island Rail Road and Amtrak trains. In 2011 Dutch Kills was beginning to transition from mainly industrial to upscale residential, and several of its older treasures such as the old Long Island Star offices, where the long-lived newspaper was produced, have fallen to the wreckers. The term “kill” is derived from middle Dutch “kille” meaning “riverbed” or “channel.” A number of NYC bodies of water are called “kills” including Dutch Kill(s), English Kill(s), and the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull between Staten Island and New Jersey. Dutch Kills and English Kills in the colonial era led to territory held by the Dutch and the British.

Crossing the Dutch Kills here involves crossing the 1908 Borden Avenue Bridge, one of four remaining retractile bridges in the USA and one of two in New York City. I’ve already written extensively on this bridge and won’t repeat myself here. That attached page has plenty of bridge photos in better weather than this.

Finding the next grade crossing involves making a right on Review Avenue and heading southeast. The LIRR Monatuk Branch parallels the avenue as well as Newtown Creek. What we see here is a defunct grade crossing just south of 29th Street that probably was a spur from the Montauk to businesses along Review and Borden Avenues.

A rusted end bumper can still be seen on the stub-end.

Though Greenpoint Avenue travels over the nasty Newtown Creek on the J.J. Byrne Bridge, it does have a local section that runs down to the creek and is duly grade-crossed over the Montauk tracks. Here we are looking south toward the creek. Directly under the Getty sign is a dead-end street that Google identifies as Railroad Avenue, but remains unsigned by the Department of Transportation.

Looking west on the Montauk tracks from Greenpoint Avenue.

Looking east on the same tracks. Note the One Way sign mounted on the crossing signal.

A look northeast on Greenpoint Avenue. You can see the distant spire of St. Raphael’s Church, one of the highest structures in the neighborhood of Blissville.

Blissville is the small wedge of Queens positioned between Newtown Creek, Calvary Cemetery and the Queens-Midtown Expressway; it takes its name from Neziah Bliss, inventor, shipbuilder and industrialist who owned most of the land in the 1830s and 1840s. Bliss, a protégé of Robert Fulton, was an early steamboat pioneer and owned companies in Philadelphia and Cincinnati. Settling in Manhattan in 1827, his Novelty Iron Works supplied steamboat engines for area vessels. By 1832 he had acquired acreage on both sides of Newtown Creek, in Greenpoint and what would become the southern edge of Long Island City. Bliss laid out streets in Greenpoint to facilitate the riverside shipbuilding concern and built a turnpike connecting it with Astoria; he also instituted ferry service with Manhattan. Though most of Bliss’ activities were in Greenpoint, he is remembered chiefly by Blissville and by a stop on the Flushing Line subway (#7) that bears his family name; 46th Street was originally known as Bliss Street.

The Greenpoint Avenue crossunder beneath the Byrne Bridge, showing signals and gates.

What does “SS” stand for, railroad buffs?

“SS on the railroad means spring switch, which means when a train leaves the siding, the switch springs back to its original position.” — Ken Voight

The Montauk LIRR branch looking east from Greenpoint Avenue.

A normally busy intersection, Review and Greenpoint Avenues and Van Dam Street. In what has to be a coincidence, there is a two-block Van Dam Street in Greenpoint, Brooklyn in the same position Queens’ Van Dam Street would be in, were it to continue south and cross the Creek.

Continuing on Review Avenue toward the next grade crossing. The avenues adjoining the Creek: Greenpoint, Review, Metropolitan, etc., are dotted with the occasional strip club. Certain areas of the city are zoned to permit them after many were forced to vacate residential neighborhoods during the Giuliani era.

The mighty Kosciuszko Bridge, which most New Yorkers pronounce “Koskee-OS-ko” but in Polish is actually closer to “Ko-SHOOS-ko” is the second bridge in the region named for a Pole who fought with the patriots during the Revolution, Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko.

The bridge replaced the small truss Penny Bridge (see below) connecting Meeker Avenue and Laurel Hill Boulevard in 1939. Since its main approach was originally on Meeker Avenue (the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway was built much later) it was at first known as the Meeker Avenue Bridge.

The Newtown Penticleer, writing for Q-Brownstoner, has many views of the iconic structure and what can be found beneath it.

The current K Bridge replaced this 1939 span in 2017, though work is now undergoing on its twin span due to open in 2020 — with that bridge containing a pedestrian and bike path. The 1939 bridge had a walkway that was quickly sacrificed to roadway expansion.

As for Review Avenue’s name, it’s long been speculated. Most likely it is named for funeral processions en route to the cemetery that are ‘reviewed’ by locals on the side of the road, or less likely, spectators in the cemetery could “review” ships passing down the Creek.

The cobblestone wall holding in Calvary Cemetery has been in place for a long time, and some of the graffiti has, too.

The LIRR Montauk Branch, little-used by freights these days, makes its closest approach to Review Avenue where it takes a bend at the Calvary Cemetery entrance and becomes Laurel Hill Boulevard.

Until March 16, 1998 the LIRR stopped at Penny Bridge…admittedly, only three times daily. Trains had stopped at Penny Bridge since 1878; at one time it had busy Calvary Cemetery clientele. Stops at Haberman, Maspeth, Fresh Pond, Glendale and Richmond Hill were also abandoned. The smart thing would have been to convert it to a cross-Queens subway line, but locals would have no part of that.

The trains stopped at Laurel Hill Blvd. within sight of the creek. In its latter days, the Penny Bridge station was nothing more than a clearing along the tracks; even in its salad days, it had merely a shed to protect passengers from the elements.

Through much of the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Penny Bridge was a toll bridge on the Bushwick & Newtown Turnpike. (end of Meeker Ave). In the seventeenth century, it was the location of a ferry between Laurel Hill / Maspeth and Greenpoint / Bushwick. The ferry was started by Humphrey Clay, an associate of Captain Kidd.

The bridge was also the main access to Catholic burials in Calvary Cemetery. The Alsop farm was bought by the church in 1837 when land became scarce for burials in Manhattan. There was a need for the turnpike for the transport of Queens produce to and from Williamsburg ferries as well as the funeral processions to Calvary.

The road connection to Penny Bridge’s former location is still there, with traffic controlled by grade crossing signs, but for several decades now it has led to a creekside junkyard.

Like Franz Kafka, I have mostly felt for the past three years or so that I am being punished by an unknown entity for an unknown crime. Best to join the hooded penitents (whose presence may once have been in the flesh other than in my dreams) and walk silently and reverently in Calvary Cemetery on the way back to the #7 train.

“Bantry Bay Tavern, Greenpoint Avenue and Bradley Avenue, and the County Cork Association speak of a tenuous Irish presence in Blissville, which is actually larger in neighboring Sunnyside. Irish immigration to the USA has ebbed and flowed in response to Ireland’s economy, way up in the 1990s but way down now.”

One of the strangest, and handsomest Best Western motels you’ll ever see on Greenpoint Avenue opposite Calvary. The City View Motor Inn was “converted” from Public School #80 in 1986. This was a surprising sight indeed as the Bay Ridge boy explored western Queens by bike before moving to the World’s Fair Borough in 1993.

Cruel snowflakes began to fall in a preview of the next series of storms, even though the feeble January sun still made a stand. Time to go home.

More grade crossings coming in Part Two.

9/7/14