Other than the BMT 4th Avenue Broadway Line (N, R, Q and now W trains) perhaps the majority of my subway rides for six decades have been on the Flushing Line, the #7 train, one of the few subways’ general east-west routes. I rode 4th Ave/Broadway when living in Bay Ridge (1957-1993) and the 7 when living in Flushing and then Little Neck since. Most of the 7 train (stops between Queensboro Plaza and 103rd/Corona Plaza) celebrates its centennial on Friday, April 21st, 2017, weeks after the Hell Gate Bridge, which transports freights, Amtrak and Metro-North trains between Queens, Manhattan and the Bronx, celebrated its first 100 years.

From its beginnings in June 1915 running one stop from Grand Central to Vernon/Jackson what has become known since then as the Flushing Line has been extended eight times: east to Hunters Point Avenue and Court Square (11/5/1916); Queensboro Plaza to 103rd Street (4/21/1917); 111th Street (10/13/1925); Willets Point Boulevard (5/7/1927); Main Street (1/2/1928) and west to 5th Avenue (3/22/1926); Times Square (3/14/1927) and Hudson Yards (9/13/2015). (A tiled sign at the Hunters Point Avenue station says the line goes “to Astoria and Corona,” referring to the split at Queensboro Plaza that sends the BMT to Ditmars and the IRT to 103rd/Corona Plaza.)

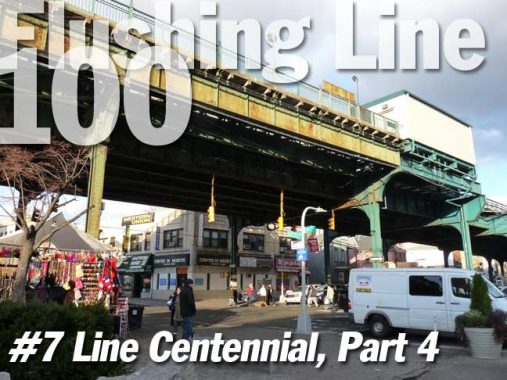

In November 2016, I walked the full length of Roosevelt Avenue under the Flushing Line to Main Street. I’ve also amassed several photos of the stations along Queens Boulevard over the years, and thus I can create a multipart FNY series on the #7 train, and what’s under it.

As always, current and vintage photos of the Flushing Line are available at NYC Subways.

We’re up to …

103rd Street/Corona Plaza

This was the original terminal station of the Corona Line when it opened on April 21, 1917. It only became the Flushing Line when it was extended to Main Street on January 2nd, 1928. In between, it reached 111th Street in October 1925 and Willets Point Boulevard in May 1927.

The original name of the 103rd/Corona Plaza station was Alburtis Avenue. My dependable table of Queens street name changes, assembled by the great Steve Morse (who I would like to meet one day) lists Alburtis Avenue as 104th Street, while maps I have of the area from 1908 and 1909 show 104th Street as Sycamore Avenue. So, 104th must have been known as Alburtis Avenue for only a short time.

104th Street, formerly Alburtis Avenue, looking north and south from the east and westbound station platforms. The two church spires in the distance in the northbound shot are Our Lady of Sorrows Roman Catholic Church (37th Avenue, 1900) and Emanuel German Lutheran Church (37th Drive; 1902). In the southbound shot, the large building on the left is PS 16.

A view of Corona Plaza from the eastbound platform. Auto traffic had the full run of the plaza, which was created when the elevated was built between 1915 and 1917, until just a few years ago, but it’s now a pedestrian-only plaza with tables and chairs during the warm months. The Walgreens drugstore used to be the Loew’s Plaza Theatre and operated until 2005. As of 2016, the Walgreens space was for rent.

For many years now, Pollo Campero has been a Corona Plaza mainstay. The chicken chain, founded in El Salvador in 1971, has become South America’s largest fast food franchise, with 350 locations worldwide including 63 in the United States. This was the chain’s first foray into New York City.

For a few years now the largest advertising sign at Corona Plaza has belonged to an oral surgeon. A fun way to spend an afternoon in Corona!

Before the land between Elmhurst and Flushing was developed in the 1850′s, there were only a dozen families living in the area. From the highest point on a hill 108 feet above sea level, they could take in fantastic views of Long Island Sound and the isle of Manhattan and could even see clear to the Palisades of New Jersey. At the lowest point at Flushing Creek, they would bring their corn and wheat to be ground into flour at a grist mill. Farms here also grew cauliflower, broccoli, cabbage, kale, pumpkins, pears, peaches, apples and grapes, and raised pigs and cows.

Ground was broken for the Flushing Railroad in 1853. This event would spark the transformation of the sleepy settlement into a bustling commercial, industrial and residential center. A real estate company was organized in Manhattan to create “West Flushing,” a name which wouldn’t last long. The West Flushing Land Company engineered the first of two major phases of development by selling houses on small plots carved out of former farmland.

West Flushing’s second phase of development was the responsibility of Benjamin Hitchcock, who also developed Woodside at the same time. He bought 1,200 West Flushing lots in 1867 and sold them in 1870. He offered installment payments to his less wealthy customers, which was a novel idea at the time, and one which they found very attractive.

Resident Thomas Waite Howard discovered that his town’s name was confusing to outsiders and even to the post office. In 1868, he petitioned the post office to change West Flushing’s name to ‘Corona’ as he felt that his neighborhood was the “crown jewel” of Long Island. The post office granted his request in 1872.

For a closer look at Corona, check out its FNY page.

On Sundays at least, Corona Plaza at National Street has become home to vendors of all types adjacent to the pedestrian mall. I like an ear of sweet roast corn, but alas, I had just recently had lunch.

Corona Plaza is also home to one of New York City’s newer public rest rooms; there’s another one at Herald Square, 6th Avenue and West 35th Street. It comes in handy when I have had tours meet at Corona Plaza.

A look north on 103rd Street to the original branch building of Queens County Savings Bank, with its large illuminated billboard sign easily visible from passing #7 trains.

Just west of Corona Plaza, there’s a short street between 100th and 102nd Street (one block) just south of Roosevelt Avenue that’s interesting. It features tract housing and a bit of street art, but the interesting part is that it has a name, Spruce Street, instead of a number. This makes it a key that unlocks some of Corona’s past!

Here’s an excerpt from a 1908 map of Corona, before the streets were numbered. I’ve helpfully added the current course of Roosevelt Avenue and the Flushing Elevated, which came along beginning in 1915. There’s a large parallellogram of undeveloped ground in the middle. Then, as now, National Street diagonals through the middle. The small bit of Spruce Street I circled in red is still there today, complete with its old name.

At Corona Plaza, Roosevelt Avenue took over the route of Grand Avenue and heads east. Grand Avenue was also the name of today’s National Street. After Queens streets were numbered, duplicate street names were also eliminated; there’s a Grand Avenue in Elmhurst and Maspeth, and there was one in Astoria (30th Avenue). Why National Street? That was a racetrack!

In 1854 the National Racing Association, a group of Southern horse owners, built the National Racetrack in Corona. On June 26, 1854, the first race was run, coinciding with the official opening of the main line of the Flushing Railroad, which created a stop for the track. In 1856, the track opened for the season as the “Fashion Pleasure Ground,” named after the champion horse, Fashion. In 1858, the track hosted the first baseball game for which an admission fee was charged. In 1861, the owners transported their horses back down South to help the Confederacy during the Civil War, so northern horses took their place. In 1867, the racehorse Dexter broke the world’s trotting record for the 1-mile course at the Corona track. Ulysses S. Grant attended a race there shortly after becoming President-elect in 1868. The last race was in 1871 and the track was torn down soon after that, remembered only by National Streetafter the name was changed from Grand Avenue.

Also of interest on the map is Linden Park. In the colonial era, there was a pond left over from a glacial retreat in which local farmers watered their cattle. As the village of Corona grew up around Linden Lake, a park was built around it and it was used for ice skating in winter and as the backdrop for band concerts in the summer. After it became mud and silt choked and contaminated the Parks Department filled it in in 1947. The familiar PS 16 is seen in the older picture. It’s now a public park called the Park of the Americas.

In 2004, I got a shot of a remaining small station ID sign on the eastbound platform. The sign was quickly removed by the MTA, which prefers to whitewash its signage history (much like the Department of Transportation), soon after I posted it on Forgotten NY.

Between 108th and 111th Streets on the north side of Roosevelt there is a handsome row of attached brick buildings with polygonal bay windows. The porches appear as if they may have been added later. These buildings may well date to before the el was constructed in these parts in 1925 and Roosevelt Ave was still called Grand Avenue. The sign in the window is pretty old since George Pataki and Jim McGreevey, NY and NJ governors, have been out of office for years.

111th Street

As I did in 2004, I photographed a leftover enamel station ID sign on one of the light stanchions. When I posted it on Forgotten NY, the MTA was made aware of its presence and removed it. Call me the Grim Reaper.

Roosevelt Avenue at 112th Street in the 1930s, showing bocce (Italian lawn bowling) courts in the foreground and houses on 39th Avenue in the back.

Food truck near the 111th Street station. Chimichurris is ground pork or beef which is sliced, grilled and served on a pan de agua (literally “water bread”) and garnished with chopped cabbage.

Shuttered woodframe house near 111th Street.

Francisco Munoz, who was 29 years old, was one of 358 employees of Marsh & McLennan Companies, Inc. that were killed during the terrorist destruction the World Trade Center. The corner of Roosevelt and 11th was named for him by the NYC City Council in 2011.

East of 114th Street, Roosevelt Avenue passes over the Grand Central Parkway, opened here in 1936; the parkway broke ground in 1931 and reached the Triboro Bridge 5 years later. What could be original railings on the Roosevelt Avenue overpass are still in place.

Roosevelt Avenue skirts the north end of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park and runs between two stadiums (stadii?): on the south side, Arthur Ashe Stadium, opened in 1997, is home to the annual US Open tennis tournament held on the weeks surrounding Labor Day. It is accompanied by the new Louis Armstrong Stadium, opening in 2018 to replace the old Armstrong, formerly the Singer Bowl, home of the Open from 1978-1996.

On the north side is the New York Mets’ home stadium, Citifield, opened in April 2009, replacing the Mets’ second home stadium, Shea Stadium (1964), which closed at the end of the 2008 season. The Mets have also played home games at the old Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan during the 1962 and 1963 seasons.

Few remnants of the old Shea Stadium remain, but the stadium’s Home Run Apple has been installed near the front entrance. It was first seen at Shea outside the center field fence in 1980, when the Mets had a “The Magic Is Back!” campaign, the top hat the traditional magician’s garb along with an apple for NYC, The Big Apple, a hopeful hark back to the 1969-1973 era when the team went to two improbable World Series, winning one. The real magic would not return until 1984, when Daryl Strawberry and Doc Gooden were called up and the team made the first of a number of acquisitions, bringing in Keith Hernandez from the Cardinals.

The apple in the top hat would rise, like magic (actually someone in the press box hit a button) when a Met hit a home run. The tradition continues today with a new home run apple.

I’ve always paid attention to street lighting. Running past the stadiums, there’s a variety on Roosevelt Avenue: lighting is mounted inconspicuously on elevated train pillars crossing the Parkway and on short cylindrical posts painted brown once past it. One element I noticed way back in 1969 when I first started going to Shea Stadium is amazingly still in place: the only instance of a fire alarm bracket lamp mounted on an elevated train pillar, above the alarm itself. It hasn’t been serviced in a long time and is about to fall off.

This wood sign under the Willets Point Boulevard station may be original from 1927, when the el arrived here. In any case it’s quite old indeed.

Willets Point Boulevard

This is one of the Flushing Line’s few express stations. During rush hours, a few trains terminate here instead of going one station east to the terminal at Main Street. This station opened in May 1927…

… and when it opened, it was one of the only elements in what was still largely a wilderness, with just a gas station, car wash and scattered industries for company.

A look at 126th Street north from Roosevelt Avenue in the 1930s. Until 1939, the general area was home to ash heaps with just Roosevelt avenue and Northern Boulevard traversing them; they were made famous by F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby in which Gatsby and the Carraways drove on Northern Boulevard past the heaps, which were punctuated by gas stations and billboard ads. Robert Moses developed them into the 1939-40 World’s Fair, the subsequent 1964-65 Fair and Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. photos: NY Public Library

The Go-Go Sixties, in which the world seemingly turned color, were distilled for the first time in 1964 during the World’s Fair, the new Shea Stadium, and new directions in entertainment and pop music such as the Beatles’ ascendance. New subway cars with a baby blue and white color scheme were introduced for the Fair, and Shea stadium originally featured differently-sized panels in the team colors of orange and blue on its exterior. (When Fred Wilpon bought the team with partner Nelson Doubleday in 1980, off came the panels.)

When it opened in 1927, this station was called Willets Point Boulevard, for the road that runs diagonally northeast from Roosevelt Avenue at this point. Plans called for that road to be bridged over Flushing Creek and head northeast toward the actual Willets Point, which is in Fort Totten, where land was purchased by the US Government in 1857 from the Willets family. However the bridge was never built and Willets Point Boulevard now exists in two widely separated parts, one here and another in Whitestone.

Over time the area surrounding the station has come to be called Willets Point and the original, true Willets Point has been forgotten!

The Iron Triangle

Describing the “Iron Triangle” other than “a place you would never go to otherwise than compelled to do so” would not be an overstatement. This small, smelly and noisy triangular neighborhood in Queens is home to warehouses, car repair and auto parts stores, and, they say, only one resident. In June 2008, I went this check out this fascinating neighborhood.

The Iron Triangle might not mean anything to you unless you got your car fixed there. It is the nickname given to a neighborhood near Flushing and Corona, Queens, better known as Willets Point. It is bounded by Northern Boulevard to the north, 126th Street and Shea Stadium (in 2009, Citifield) to the west, Roosevelt Avenue to the south and the Flushing River to the east.

Over the past decades, this run-down 60-acre neighborhood has become home to car repair, auto parts stores and other larger businesses, including waste facilities and warehouses. An April 2006 Hunter College study called it “a unique regional destination for auto parts and repairs.” In all, an estimated 225 firms are established here and from 1,400 to 1,800 people work here, according to the study. –Alexis Buisson, in Forgotten New York in 2008

I walked the “Iron Triangle” again as part of my Roosevelt Avenue jaunt in November 2016. This is a region that the City has sought to get rid of for decades and render it available for redevelopment. “And yet, it persisted.” It is still home to auto repair, tire repair, auto glass shops, and other businesses. The city has never installed sewers and has not resurfaced the roads or repaved them in decades. Many of the auto shops have moved out, but some are still hanging on. As I walked, my pants and shoes were swiftly caked in mud.

Until his death in 2016, Joseph Ardizzone, a security instructor, lived in the two-story house where he was born at 126-96 Willets Point Boulevard; on the ground floor is the Master Express Deli, which serves lunch to the local laborers.

Plans for redevelopment are reported year after year, but I suspect the triangle will remain Iron for the near future.

Roosevelt Avenue rolls on, across its namesake double-deck, double-leaf bascule movable bridge across Flushing Creek. The bridge was built between 1923 and 1927 and carries both the Roosevelt avenue roadway and the Flushing Elevated. A complete renovation of the bridge, to be done while keeping it open to traffic, commenced in 2015 and is not expected to be finished until 2019.

The Sloane Furniture Clock Tower, the longtime home of Serval Zipper and now a U Haul center on College Point Boulevard, was a familiar sight behind the Shea Stadium outfield fence.

East of the Flushing River, the former town, now neighborhood of Flushing appears atop a slight rise. This gave the BMT/IRT the opportunity to plunge the Flushing Line into a tunnel to the Main Street terminal. For decades the territory on either side of Roosevelt Avenue was a no-man’s land of abandoned factories and warehouses, but these have been razed and massive shopping centers and new high-rise apartment towers have arisen in their place.

The James A. Bland Houses in Queens is a 6.19-acre development with five, 10-story buildings featuring 400 apartments that are home to some 878 residents. The complex was completed on April 30, 1952. Bland was an African American composer & minstrel singer in the late 1800’s, who was a native of Flushing; he was known as the “World’s Greatest Minstrel Man.” Among his hits were “Carry Me Back to Ol’ Virginny” and “Oh! Dem Golden Slippers” (a favorite of the old man’s when playing his squeezebox).

The east end of the Bland Houses leaves you at 40th Road and Prince Street, seen here facing north, in downtown Flushing, named for horticulturalist William Prince, who established a commercial plant farm, or nursery, in western Flushing in 1737 along Flushing Bay. He first limited his business to apple, plum, pear and other fruit and flowering trees, and later expanded to shade and ornamental trees.

Other plant nurseries appeared in Flushing during the 1800s; one of the more successful was Samuel Parsons’, whose family gave Parsons Boulevard its name. Parsons brought the popular pink-flowered dogwood from Europe, as well as planted a weeping beech tree in 1847 on what is now 37th Avenue that survived 150 years. Its descendants, grown from cuttings, are still there. Flushing’s streets are still named for plants in alphabetical order from Ash to Rose.

If you thought the buildings along Roosevelt Avenue in Elmhurst and Jackson Heights were heavily padded with signage, get a load of 40th Road between Prince and Main. This is the heart of NYC’s second major Chinatown.

The windows of 40th Road are chockablock with foodstuffs from live crabs to recently cooked hanging fowl to fresh fruit.

It was time to kick it in the head after walking nearly the full length of Roosevelt Avenue. I ascended the elevated Long Island Rail road platform which affords a view of Flushing’s 15-year-old library building, which stands in the spot where two previous libraries served Flushingites at the V formed by Main Street and Kissena Boulevard, a very old road once called Jamaica Road as it took the course of today’s Kissena and Parsons Boulevards south to that neighborhood.

I’m not good at night photography so I’m going home at just the right time.

Happy 100th, Flushing Line!

“Comment…as you see fit.”

5/8/17