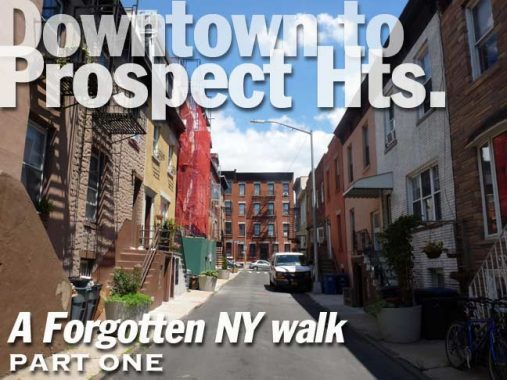

Another entry in FNY’s deck-clearing exercise. I took these photos in mid-July 2017, when a front had passed and the dead dog heat and humidity had lifted just a bit. My favorite weather for Forgottening is the first day after a front passes and the sky is as clear as it ever gets in NYC during the summer. Along this walk from downtown Brooklyn, into Cobble Hill, Park Slope and Prospect Heights, I went past some Forgotten NY favorites, and as always, made new discoveries.

GOOGLE MAP: DOWNTOWN to PROSPECT HEIGHTS

I’ve always been fascinated with a restaurant in downtown Brooklyn I never actually got the chance to patronize. I went to school on Remsen Street between Court and Clinton (St. Francis College) yet, rarely went out to lunch, preferring to brown bag stuff, or eat at Woehrle’s across Remsen or the Burger King on Montague. I never went into Gage & Tollner on Fulton just off Smith, but I was aware back then that the proprietors kept the place looking just the same as it did when it had first opened decades earlier, with polished mirrors and wood chairs and tables, gaslights that had been converted to electric, an old-fashioned seafood menu, and several waiters who had been on staff for years.

Charles Gage & Eugene Tollner’s venerable Brooklyn restaurant at 372-374 Fulton Street just west of Smith Street had been in business since 1879 and had occupied its Fulton Street brownstone building since 1892. Signs in the window proclaimed it as “New York’s Oldest Restaurant” but that title is disputed; my Bible in these matters, Ellen Williams and Steve Radlauer’s The Historic Shops and Restaurants of New York, claims that the Bridge Cafe, on Dover and Water Streets in Manhattan’s Seaport area, has been a restaurant of some kind since 1794, but perhaps Gage & Tollner meant “oldest restaurant under its original name.” In any case, the Bridge Cafe has been closed since it was ravaged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

A look inside G&T, even through the display window on Fulton Street, provided a glimpse back in time, as moulded cherrywood, beveled glass windows and gaslamps converted to electricity gave it a distinct Victorian patina. Some of the waiters had been in service for decades.

Real estate records show that the brownstone building occupied by Gage & Tollner dates to 1875. Many such old buildings survive along this stretch of Fulton Street, but most of the top floors are abandoned and in any case have not been kept in the condition this one has been.

Gage & Tollner was known as a seafood restaurant with clams and oysters a specialty. The restaurant seemed to be a bit pricey, especially for the Fulton Mall area. Over time Gage & Tollner found it harder to attract customers, despite hiring a string of acclaimed chefs. This gradual attrition made it too difficult for its owner to keep Gage & Tollner open.

For a time the roast beef fast food chain Arby’s occupied the space (their lengthwise sign is still in place), and since 2012, a discount jewelry and clothing store. All the while, store displays covered up the mirrors and woodwork, but the gaslamps hanging from the ceiling were still in public view. I took a peek inside, and got a tantalizing glimpse of what still could be.

In 2016, word went around that the building’s new owner would like to turn the space back into a restaurant. We’ll see what happens.

#1 Smith Street is a stolid, stone-clad, fortress-like building on the SE corner of Fulton and Smith Streets, home to local service organizations and a Duane Reade on the bottom floor. There is something interesting on the Smith Street side. Take a look at the picture windows with the rusted metal exteriors next to the entrance. Look carefully above each window, and the Schrafft’s logo can be seen on each panel.

The restaurant chain was founded by Frank G. Shattuck, who expanded William Schrafft’s candy business founded in Charlestown, Massachusetts in 1861 into chain restaurant empire beginning in 1898. For a time it was as ubiquitous as its successors, Chock Full O’Nuts and McDonalds. By the 1960s, Schrafft’s (like Howard Johnson’s, it sold branded ice cream) seemed passé and even hired Andy Warhol to snazz up its image, to no avail. Schrafft’s was purchased by the Risse Organization in 1978, which converted Schrafft’s outlets to other restaurants in its umbrella, such as TGI Friday’s.

Midday Havens, Lost to a Faster-Paced City [NY Times]

“The Hottest Coffee Around” ad, visible on Fulton Street for a decade at least, was finally painted over shortly after I got this photo in July 2017. It was probably a McDonald’s ad; ironically, McD’s has been sued because their coffee was too hot.

Red Hook Lane runs from Fulton Street at Pearl Street southwest to Boerum Place at Livingston. It’s one of the oldest streets in Brooklyn; it existed in the colonial era, as shown on this J. Ratzer map of Brooklyn (use the arrows to zoom in) from 1766, occupying the same place it does today — it can be seen as a white line running southwest from the yellow line representing today’s Fulton Street (which was then part of the original Kings Highway, but that’s a long story for another page) and even then, the map shows it as Red Hook Lane. It likely follows a Native American trail.

In 2004, word came that Red Hook Lane was on its last legs, as it would be demapped and built over and a high-rise sprout in its place, so I put together a FNY page about it. Happily, the high-rises have sprouted elsewhere.

Red Hook Lane inspired the name of a new luxury apartment building, The Lane at Boerum Place (corner of Livingston). The cheapest apartment costs $2,492 a month, which doesn’t sound outrageous by Brooklyn standards now, but it must be a basement studio.

Check Street View in 2009 to see what had been here.

The 1900 Beaux-Arts 131 Livingston Street is now hemmed in by glass boxes to its east and west. The design was by C.B. J. Snyder, who built dozens of public schools in NYC in the same era; Snyder was also Superintendent of Buildings for the Board Of Education between 1891 and 1923. 131 was the headquarters of NYC’s Board of Education before that entity moved to nearby 110 Livingston in 1940. Now known as the Department of Education, there are still some offices in this building, which wraps around the corner to Red Hook Lane.

Around the corner on Smith and Schermerhorn, here is the General Court Building, a stolid Depression era exercise in late Beaux-Arts construction. Why did I shoot at such a high angle? Probably lots of moving traffic. The building features three massive arched entrances and Corinthian pilasters (half columns) on the Schermerhorn side.

If defendants at the General Court Building lost their cases, some were shuffled a block away to Atlantic Avenue between Smith Street and Boerum Place, to the Brooklyn House of Detention, a decidedly non-luxury high rise completed in 1957 (the same year I was completed). It has been unoccupied in recent years but the City is always trying to reopen it, to the neighborhood’s consternation. Since many of the current spate of politicians wishes to close Rikers Island, those waiting for trial might find themselves here sometime soon.

Some of Atlantic Avenue’s gritty reality will be obvious to residents of the Nu Hotel if they face the Atlantic Avenue side, where there are a string of bail bonds offices serving the Brooklyn House of Detention, or to a newer place at Smith and State on the ground floor of a parking lot building adjacent to the hotel.

The gentrifiers have glommed onto the zeitgiest, with a jail across the street, courts up the street, and bail bonds offices to the north and south, it was inevitable that a tapas joint calls itself … Misdemeanor.

Just about the entire stretch of Smith Street between the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and Atlantic Avenue has been subnamed for a popular Assemblywoman who served from 1980-1996 and died at the young age of 51 that year.

Eileen Dugan or Eileen Duggan? A Woodside crossing guard with an almost identical name has also been honored with a street sign.

Though NYC is not known for many French enclaves, Boerum Hill comes closest, Bar Tabac, at Smith and Dean Streets, helps host an annual Bastille Day celebration every July–playing host to 20,000 attendees.

Outside the Bergen Street subway entrance on Smith is a wooden pole with what appear to be directional signs. Actually it is an art installation by artist Sasha Chavchavadze memorializing the Battle of Brooklyn, played out in the Brooklyn countryside in August 1776, in which though the British routed the patriots, enough were able to escape to fight another day.

The sixteen-foot mahogany pole at the corner of Smith and Bergen Streets has a metal weathervane affixed to the top; beneath the weathervane are three wooden directional signs pointing toward where the Battle took place: the Gowanus Canal; Manhattan; and the corner of Court Street and Atlantic Avenue, where George Washington is said to have stood watching the slaughter of Maryland farm boys, many of them barefoot, fighting the British. Text from Walt Whitman’s poem, about the battle, “The Centenarian’s Story,” is burned onto the wooden signs: Do you hear the clank of the muskets?; in the midst of you; pavements and stately houses disappear; the years recede; pouring about me here on every side; an encampment very old. [Sasha Chavchavadze]

The installation reminds me of the former striped signposts pointing traffic to Queens locales that were nearly ubiquitous in the 1920s and 30s, but completely absent today.

“Artisanal” is a word you will see frequently in northern and western Brooklyn; it’ simply a highfalutin’ word for “homemade.” At first I thought this place was named for the guitar player and composer in the Dutch group The Shocking Blue, Robbie Van Leeuwen, but that was almost 45 years ago. Actually this is an artisanal ice cream palace at 81 Bergen Street near Smith, that has other branches in Greenpoint and the East Village, and they also sell from roving trucks, owned by Ben and Pete Van Leeuwen.

Since last summer I have been laying off sweets and bicycling more, which shaved 15-20 pounds, but I have to keep at it, so artisanal ice cream, or plain Sealtest, is restricted to a couple times per year.

In the 1880s, architects often handily inscribed the date of construction and sometimes the original owner of the building, on the pediment or elsewhere. So it was here at #87 Bergen, a.k.a. The Bergen.

I always look for interesting store signage. The Music Store is a relatively new entry at #177 Smith between Wyckoff and Warren Streets. On Smith Street, there is a large amount of turnover in the street scene, with businesses failing and others taking their place. To prove my point, check FNY’s first Smith Street page from 2008.

The massive Rite-Aid at Smith and Warren is a former J. Michaels furniture store. Michaels, “the friend of the people,” was in business over a century before merging with the Muriel Siebert Financial Corp. in 1996. If I remember correctly, I purchased a recliner at a J. Michaels on 5th Avenue in Park Slope in the Easy Eighties that stayed with me at three separate apartments before I moved to Little Neck. I’m still a bit unsure why I didn’t keep it.

<<Years earlier, I had found this Pepsi ad on Hicks Street with the “Taste that Beats the Others Cold” tag, which was used in the late 1960s. Sadly this ad has since vanished.

Smith Street, looking north from Sackett. The bikes at the bottom are affixed to stanchions on a public bike parking spot on the east side of the street.

The bikes are parked in front of this mysterious storefront, which has animal figurines and a poem called “Figure in a Landscape” in the window (which was also a painting by Irish artist Francis Bacon) and a citing of W. S. Merwin. Normally, I’d think this was a social club and it would be best to not knock and expect much info, but maybe someone could fill me in.

Between Bergen and President, a pair of engaging signs. Smith Laundromat hasn’t changed its sign in decades –it gets the job done–while Michael’s Shoe and Watch Repair incorporates a clock into the sign.

The subway entrance/exit at President is directly in front of the seasonal Gowanus Yacht Club, a drinkery of which I have heard much but have never entered. Owners Alan Harding and James Mamary have run/designed many restaurants on Smith Street including the defunct Patois, Union Smith Cafe and Trout.

At 3rd Street (Smith Street has numbered Streets east of it, numbered Places west of it) the IND Subway constructed in the 1930s charges above ground, or ducks underground, depending on from where you’re coming.

Here we find the Smith Street substation, containing electrical relays that help power the third rail. The exterior contains some prime Art Moderne styling such as decorative metalwork, sanserif lettering, and patterened brickwork.

IND styling (1925-1940) isn’t as celebrated as the earlier Heins and LaFarge Beaux Arts stations from 1904-1908, or even the Squire Vickers “Arts and Crafts” BMT stations that followed them (1908-1928) but this is just as evocative of a bygone age. For a great look at subway signage and infrastructure, the Transit Museum’s Subway Style can’t be beat. And, I just discovered that the distinctive font used in IND stations has been digitized, but unfortunately doesn’t seem to be available for purchase.

In the 1990s, local kids from area public schools painted a mural on the concrete wall on the subway ramp outside Smith Street. They have faded by now, and local taggers let it be for a few years, but not any more.

The IND subway features its only two elevated stations at Smith-9th and 4th Avenue. When the line was built out to Park Slope in the early 1930s, it was decided to cross over the Gowanus Canal instead of tunneling under it, and so Smith-9th is the tallest station in the system, almost 90 feet over the canal. The station was completely renovated a few years ago and got a fresh set of escalators.

Meanwhile, the steel pillars of the elevated are clad in concrete. After 70 years, the concrete was beginning to crumble, endangering anyone driving or walking underneath them, so hey were clad in canvas for a few years, then rehabilitated and repainted; they look as good as new these days.

Looking east on 5th Street toward the largest concrete plant in the city, Ferrara Brothers. In 2017, the firm was planning to move to Sunset Park, perhaps clearing the way for more residential construction along the Gowanus Canal, which has been the trend over the past decade.

Long a Forgotten NY favorite, Dennet(t) Place is a one-block alley just west of Smith, between Luquer and Nelson Streets, lined by small dwellings that wouldn’t have been really out of place in an urbanized Shire, since the doorways leading to their basements seem designed to only admit hobbits. Dennet Place is lined with small, two and three-story attached houses, some with dormers, some without. They are arranged in groups of two, with a double staircase in the middle serving each. Below the stairs, each house has a miniature door, most about 4 feet in height.

To those who are not Cobble Hillers, or are otherwise unaware of the area, coming upon this narrow lane is a revelation. They just don’t make them like this in alley-poor New York City. I can’t account for its origins, or the derivation of its name; perhaps it’s as simple as a guy named Dennet lived here. It’s been here a long time, though — Dennet Place turns up in this city directory published in 1876. The Department of Transportation has both Dennet and Dennett signs at either end, and Google Maps says it’s Dennet; I imagine one “t” is ultimately correct, but I made my gif before I realized it.

Why call a bagel shop at Smith and West 9th “Line Bagels”? Well, it used to be called “F Line Bagels” with the F in an orange circle, as on the subway car sign, but the MTA used its legal muscle to force the owner to get rid of the F bullet. Why this innocuous bagel shop became the object of the MTA’s ire is hard to ascertain.

This neat row of aluminum-sided, dormered buildings on Smith Street south of West 9th was formerly absolutely cluttered with colorful, eclectic signage for the Russo Realty Company. These signs were of course chronicled by FNY and can be seen on my 2005 Gowanus Canal page.

When the Gowanus Expressway, originally Parkway, was constructed in the 1940s it, too, was raised 90 feet above the canal. Why the clearance? In the 1930s and 1940s, tall-masted boats still worked the Canal and bridges had to be high enough for them to clear the masts.

I rhapsodized about the new Smith-9th Street Station renovation when the formerly decrepit elevated station was unveiled in 2013. However, I have never warmed up to its 9th Street entrance, which looks like a rejected 1950s vacuum cleaner design. A matter of taste, I suppose.

Some views of Lavender Lake (which is less lavender since a long-broken pump was repaired a few years ago) from the bascule 9th Street Bridge, completed in 1905 and completely rehabilitated in 2000. Since the early 1930s the IND Smith-9th Station has towered over it.

Somehow, I don’t think the designers of this 9th Street mural project thought things completely through. The sign can be creatively cropped…

And on that note FNY will leave things where they are. Next week: Into Park Slope and Prospect Heights.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

4/1/18