Another entry in FNY’s deck-clearing exercise. I took these photos in mid-July 2017, when a front had passed and the dead dog heat and humidity had lifted just a bit. My favorite weather for Forgottening is the first day after a front passes and the sky is as clear as it ever gets in NYC during the summer. Along this walk from downtown Brooklyn, into Cobble Hill, Park Slope and Prospect Heights, I went past some Forgotten NY favorites, and as always, made new discoveries.

GOOGLE MAP: DOWNTOWN to PROSPECT HEIGHTS

When I left off last week I had crossed the 9th Street Bridge over the rushing and dynamic Gowanus Canal. I continued on 9th Street a ways, on my way to Fulton Street in Prospect Heights. I’ve covered this route before, a few years ago, but NYC is eternally changing, and new things await the walker when paths are retraced every couple of years.

It bears mentioning that Brooklyn’s numbered streets, unlike Queens,’ have been numbered from the git-go. In Queens, the currently numbered streets have borne names, in some cases, more than one, in the past. Brooklyn’s city planners were differently-minded, and saddled the borough (originally a city) with several separate systems of numbered streets, including North, South, East and West, Bay, Beach etc., the Places found in Carroll Gardens, and the un-prefixed streets and avenues found in Park Slope, Sunset Park, Bensonhurst, Borough Park and Bay Ridge. And we won’t get started on the lettered avenues of Flatbush.

Above we see the lime-green exterior of Big Reuse at #69 between the canal and 2nd Avenue, its mission fairly plain as a recycling center.

Some residential buildings between 2nd and 3rd Avenues on 9th Street. The massive IND elevated train runs behind the second building, and residents along this stretch have had to get used to noise from passing trains.

I have visited Four and Twenty Blackbirds on 3rd Avenue and 8th Street. It hakes its name from the British nursery rhyme couplet, “four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie,” and as you would expect, specializes in handmade pies and coffee, with different offerings each day. (The fare is quite good; I’m trying to watch my carbs, so did not enter today.)

A couple of doors over this panini shop tales its name from the expression Joe Pesci used to refer to the “two youths” he was defending as attorney Vinny Gambini in the 1992 courtroom comedy My Cousin Vinny.

This corner building at 3rd Avenue and 7th Street was once home to the Morbid Anatomy Museum, an exhibition space founded in 2014 by a group of historians and artists led by Joanna Ebenstein. The space focused on forgotten or neglected histories through exhibitions, education and public programming. Themes included nature, death and society, anatomy, medicine, arcane media, and curiosity and curiosities broadly considered. The artifacts featured in its rotating exhibitions were drawn from private collections and museums’ storage spaces [wikipedia].

While its exhibits and artwork, many concentrated round the human body and its diseases and aberrations (much like Philly’s Mütter Museum), were well-received by its cognoscenti, the museum didn’t earn enough to make rent and unfortunately closed in December of 2016. I had visited in October 2015 and got some photos of what was on view.

A possible former stables (brick building) at 3rd Avenue and 6th Street. The surroundings here have been industrial for decades, with various manufacturing and metalwork.

Washington Park, located between 4th and 5th Avenues and 3rd and 5th Streets, for many years was called John J. Byrne Park when it was founded in the early 1930s, for the Brooklyn Borough President at the time and the savior of the Old Stone House (see below). In the early 2000s, an effort spearheaded by Stone House curator Kim Maier got the park’s name changed to its original name, Washington Park, for the 1st US President and also as a nod to the park’s legacy as a former home of Brooklyn’s Major League Baseball team known by a variety of names during its tenure here including the Superbas and Bridegrooms, but ultimately as the Dodgers. Byrne fans fear not, his name is still on the park’s playground and also on the J.J. Byrne Bridge that takes Greenpoint Avenue over Newtown Creek.

My friend David Dyte’s Washington Park research

The Old Stone House, an over-300 year old cottage officially known as the Vecht-Cortelyou House, has seen war. It’s also seen baseball.

What we now call the Old Stone House was originally built in 1699 by Klaes Arents Vecht, who had arrived from Holland in 1660. The house remained in the Vecht family until just prior to the American Revolution, when it was rented to an Isaac Cortelyou; his father, Jacques, bought the property in 1790, and the house continued on with the Cortelyou family until 1850 when it was sold to Edward Litchfield, who is most famed for dredging Gowanus Creek, creating the Gowanus Canal. Walt Whitman noted that the house was known as “the old iron nines” from the Dutch practice of affixing the building date in large iron numbers on the stones. They can still be seen there.

Apparently, Litchfield allowed the house to literally sink into ruin: by the 1890s only its upper floor was visible above ground level; after serving as a makeshift clubhouse for the Brooklyn Bridegrooms baseball team playing in nearby Washington Park (see the David Dyte link above). The house was demolished in 1897, and its construction was so solid that Gatling guns were used to force the old stones apart.

The house found an angel in Brooklyn Borough President John J. Byrne. The Old Stone House’s original foundations and brick were rediscovered, and Byrne, in one of his final acts as beep before his death in 1930, ordered its reconstruction in a park, originally named for George Washington but posthumously named for him in 1933. The Old Stone House received a thorough makeover in 1996 with new plumbing, electrics and roofing installed.

The Old Stone House had played a pivotal role in the American Revolution. On August 27, 1776, during the Battle of Brooklyn, things looked dire indeed for the Americans, as the British and their hired hands, the Hessians, were overwhelming them in what is now the northern section of Prospect Park. Hoping to reach forts at Boerum Hill and Fort Greene, about 900 American troops retreated from what would be the Green-Wood Cemetery area; they hoped to track northward. General William Alexander, also known as Lord Stirling, led a company of 400 Maryland troops that engaged British General Charles Cornwallis’ force of 2000 grenadiers and cannoneers at the Stone House to cover the retreat and, while many of the Americans were able to escape, Stirling was captured and 259 of the Maryland troops were killed. George Washington, observing the battle from what is now Cobble Hill, is said to have uttered: “What brave fellows I must this day lose.”

The battle is commemorated at the Stone House, which flies the Maryland state flag; by Prospect Park, in which a monument to the Maryland 400 can be found at Lookout Hill; by the William Alexander Middle School, on 5th Avenue across the street from Washington Park; by Carroll Street, named for Charles Carroll of Maryland, who dispatched the 400 and became the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence; and by a Brooklyn street which spells General Alexander’s name incorrectly, Sterling Place.

Brick row on 3rd Street facing the park. There’s a technical architectural term for them, but I have always liked the window arrangement here, allowing residents a look up and down 3rd Street and, varying by time of year, sunrise and sunset.

This church at 6th Avenue and 2nd Street, now part of the apparently controversial New York City Church of Christ, was originally part of The Evangelical Lutheran Church of St. Matthew, one of the oldest extant congregations in North America (it was founded in 1664). I have a particular memory of it because friends lived across the street in the 1980s, and I would always hear the loud Sunday services when visiting that day. I also noted its unusual rectangular campanile.

This 1964-era Brooklyn street sign still hangs in Park Slope. Of course, FNY fans know that NYC street signs between 1964 and about 1984 were color-coded by borough (Brooklyn, white on black; Bronx, white on blue; Queens, the reverse, blue on white; and Manhattan/Staten Island, black on gold). Since then, except for certain neighborhoods and landmarked districts, street signs are white on green, in a variety of type fonts and upper/lowercase.

7th Avenue, the main shopping drag of Park Slope, looking north from 1st Street and from Garfield Place. One of the hallmarks of corner residential architecture in Park Slope is the chamfered corner, with windows from which the passing scene can be viewed from multiple direction. What a stroke of genius it was to position windows like this!

I’m happy to see that Rancho Alegre, an old-school Mex joint, still holds forth at 7th and Garfield. I had the best taco platter I ever had at this place. Granted, my sample size is not as great as others’.

Polhemus Place, one of a pair of Places with Fiske Place, between Garfield and Carroll and 7th and 8th Avenues, named for Dominie Johannes Theodorus Polhemus, who founded the nearby First Reformed Church (one of whose churches is on nearby 7th Avenue) in 1654.

Just east of Polhemus on #233 Garfield is the former Pink House of Park Slope. It was meticulously kept that way for many years by an elderly owner despite objections by some neighbors, who feel the color is out of character on the brownstone block. Most like it just fine.

Pretty in Pink [New York Times]

The house is no longer pink, as it was sold by its elderly owner in October 2012 for $2 million.

8th Avenue and Carroll Street. General Antonio de Santa Anna (1794-1876) led the Mexican Army that defeated a ragtag assembly of about 200 American defenders at the Alamo in what would be San Antonio, Texas in March 1836. Colonel Henry Travis drew a literal line in the sand and asked all who would fight to step over it. Jim Bowie and Davy Crockett were among those who did.

Santa Anna was unique. He was a head of state who led his country into battle personally; he had several horses shot out from under him and lost part of his right leg, which he paraded with and placed on a prominent monument. His slave Emily Morgan was immortalized as “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” He was president of Mexico several times; after being exiled in 1855, he moved to the United States, where he spent 11 years plotting a return to power. It was during his exile that he had a hand in inventing … chewing gum.

In the 1860s Santa Anna boarded in Staten Island with a photographer named Thomas Adams Jr. Santa Anna suggested that Adams might be able to make a fortune off chicle, a gummy substance Mexicans had been extracting from sapota trees and chewing on for centuries. Santa Anna believed the chicle could be combined with rubber to make better carriage tires, but that turned out to be a red herring. After a year, Adams was stuck with a warehouse full of chicle, bewildered about what to do with it. Then he remembered what Santa Anna had said about chewing it. Adams’ first brand, Adams New York No. 1, was a pure chicle gum without flavoring. It was originally a flop, but gradually started to sell better, and by the 1870s, competitors began to come out with flavored varieties. By 1899, Adams became chairman of the board of directors of the American Chicle Company, an organization of the leading chewing gum manufacturers. Chiclets appeared in 1914, Dentyne in 1916, Fleer’s Dubble Bubble in 1928, and Trident Sugarless in 1962.

By 1888 Adams was wealthy enough to commission C.P.H. Gilbert to build a grand Romanesque house on 8th Avenue and Carroll Street. Its entrance arches remind you of the Astral Apartments in Greenpoint but this one is more intricately carved. The Adams mansion also features two polygonal towers, a triangular panel above the entrance, and dormer windows. At one time it boasted an old-timey elevator, one of those “birdcages” you see in old movies like The Maltese Falcon. It was removed after four of Adams’ servants were trapped inside it after it stalled; according to some reports they were trapped for weeks while the Adameses went away for the summer, and they died. Their ghosts are said to haunt the old place.

For many years, until 1950, Coney Island hot dog king Charles Feltman’s mansion stood across the street on 8th Avenue.

70-72 8th Avenue, at Union Street, was originally a residence designed by Lansing C. Holden for a Mrs. M.V. Phillips and constructed in 1887, a great example of eclectic Romanesque Revival/Queen Anne architecture with its assorted dormers, turret (which has jeweled glass embedded in its stained glass windows) and chimneys. It served as a restaurant and club in the 1930s, before falling into semiruin in the 60s and 70s. Here’s a cold weather photo when it is better visible.

Who is that guy at Grand Army Plaza? General Gouverneur Kemble Warren (1830-1882). A surveyor and engineer by trade, he arranged a last minute defense at Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg; while he was regarded as an architect of the Northern victory there, he was less successful at the Battle of Five Forks in Virginia and was relieved by General Philip Sheridan. Warren is depicted with a spyglass in his left hand, a tribute to his surveyor’s trade.

Warren was born in Cold Spring, NY. He remained in the Army after the war, working in surveying and harbor improvements. Another statue of Warren was erected at Round Top at Gettysburg, on the 6th anniversary of his death.

The Grand Army Plaza area has a number of statues and representations of “Guys” you may not know. FNY’s Who Are Those Guys? in Grand Army Plaza takes care of that for you.

The triumphal arch at Grand Army Plaza, the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, needs no introduction, but there are a couple of tidbits about it that you may not have known. It has a working elevator, for example, and there are two reliefs on the each side of the arch by artists William O’Donovan (Abraham Lincoln and U.S. Grant) and Thomas Eakins (their mounts). The Lincoln sculpture is said to be the only known portrait of Lincoln on horseback. General William Tecumseh Sherman laid the cornerstone in 1889 and the arch was unveiled on October 21, 1892.

The 4-horse chariot grouping at the top, known as a quadriga, famously blew off during a windstorm in 1976. The arch’s copper statuary, which also depicts America’s Revolutionary-era armed forces, was green with verdigris at that time, but has been marvelously restored in recent decades.

The main branch of the Brooklyn Public Library, perched in a wedge formed by Flatbush Avenue and Eastern Parkway at the north end of Prospect Park, sits on a motorized traffic nexus as well as a bike lane junction, and pedestrians have to keep an eagle eye and all of their wits to avoid being crunched by wither sort of vehicle here.

Though the BPL was long in the planning, originally due to appear in the 1910s, replacing a reservoir (just like its cousin on 5th Avenue and West 42nd in Manhattan) but funds ran out, and it did not appear until after the worst effects of the Depression had subsided, finally rising between 1939 and 1941 [Githens and Keally, arch.] Originally, a Beaux=Srts Classical library designed by Raymond Almirall was supposed to be built.

The exterior was built using Indiana limestone in a more subdued classical style, with a concave entrance that echoes the shape of Grand Army Plaza. Its hallmarks are the huge rectangular windows, spanning two stories, and the esoteric artwork on the doors, reliefs designed by German immigrant Carl Paul Jennewein, depicting the evolution of the arts and sciences. Jennewein also designed the murals, “Commerce” and “Labor” seen in the font lobby. The reliefs include characters from works by Hawthorne, Irving and Twain and also show items like archy and mehitabel, Don Marquis’ sentient cockroaches, Bre’r Rabbit, Winken, Blinken and Nod, and even Brooklynite Walt Whitman himself.

Like most Brooklyn kids I spent plenty of time in the Library doing research in the days before the internet. But sometimes, I’d immerse for hours by studying the contents of the library’s map drawer; who knows if that still exists.

The glass-exterior residential building On Prospect Park was a late addition to the Grand Army Plaza scene. It was completed in 2008 with a design by Richard Meier, master of the glassy apartment building (see the pair that flank Charles Lane in the West Village).

Here’s a more traditionally-styled apartment tower, Copley Plaza, at #41 Eastern Parkway and Underhill Avenue. It was developed by developers/architect brothers Joseph and Louis Shampan of Brooklyn Plaza realty, Jewish architects who designed upscale dwellings for people many of whom were moving out of the Lower East Side; in a way, Eastern Parkway is the Bronx equivalent of the Bronx’s Grand Concourse.

Brooklyn Plaza Reality gave #41 the fancy name of Copley Plaza and advertised it as the equivalent of living on Park Avenue. An ad in 1926 called it “Brooklyn’s Finest Apartment Building” with the “generous size of rooms that will draw a cry of delight from home loving women”. The building was ready for occupancy in the fall of 1926. A year later an ad appeared calling it luxurious, the equivalent of Park Avenue, and “The Aristocrat of Apartment Dwellings”. One ad mentioned the luxurious lobby and carpeted corridors. All the ads stressed ease of access to Manhattan: with the new Brooklyn Museum stop open, subways times were said to be 12 minutes to Wall Street, 22 minutes to Times Square. [CuRBA]

A pair of apartment buildings with historic names. Monticello was the name of 3rd US President Thomas Jefferson’s mansion outside Charlottesville, Virginia. A representation of the mansion is on the reverse of the US nickel, and appears on some editions of the two-dollar bill, with a portrait of Jefferson on the obverse. The Nancy (Hanks) Lincoln, meanwhile, is named for Abe Lincoln’s mother (1784-1818), a distant relative of Academy Award-winning actor Tom Hanks.

The name of Tooker Alley, at the patriotic corner of Washington and Lincoln, has a colorful past.

I brought a tour group into Lincoln Station, Lincoln Place just east of Washington, after a Grand Army Plaza tour a couple of years ago, and liked the chicken sandwich so much, I return when I’m in the area. No Diet Coke, so I settle for water or San Pellegrino soda.

Turning left on Classon Avenue, I encountered the massive twin-towered St. Teresa of Avila Church at Sterling Place. One of the copper campanile domes has been renovated, the one with the clock; the other one is still verdigris’ed. The parish was founded by Bishop John Laughlin, the first Archbishop of Brooklyn, and the cornerstone was laid in 1874, with the church building completed in 1887. The towers appeared in 1905, with the belltower furnished with a chime of 10 bells from the Meneely Bell Company of Troy, N.Y.; each bell is inscribed with the name of an Irish saint. Its parochial school across sterling Place is also venerable, rising in 1883.

On Classon and Prospect Place you will find the old Brooklyn Jewish Hospital, which incorporated in 1901 and opened this building in 1927. Albert Einstein had surgery performed here in the early 1950s. In 1979, Brooklyn Jewish filed for bankruptcy and merged with St. John’s Episcopal Hospital in 1982 to form Interfaith Medical Center. In 2000 Interfaith relocated its entire facility to the former St. John’s facility across the street. The old hospital is now luxury residences.

I have a personal memory of Brooklyn Jewish Hospital. I went in there just once, in 1975, to visit an ailing classmate in high school, Fred Costanzo. Though Fred was undersized, he was an agile athlete and active in our school’s extracurricular activities. Late in our senior year, Fred contacted leukemia and though he seemed upbeat when I and other friends went to see him, he succumbed during the summer in an era when there were not the life-extending treatments for leukemia available today.

Thus, I always feel the pull of nostalgia when I’m in Prospect Heights and walk past the old place.

Having not eaten yet I turned right on Bergen Street and stopped into Berg’n, a food/beer hall at #899 featuring various eateries like Mighty Quinn, a barbecue place; Landhaus, burgers, grilled cheese, salad etc.; and Maizey Sunday, tacos. It was founded by the pair of enterpreneurs, Jonathan Butler and Eric Demby, behind the successful flea market franchise, Brooklyn Flea, and Smorgasburg, a food vendor; both have set up at various areas around town, but Berg’n is the first “brick and mortar” eatery in their stable. Butler is a former employer of a sort, since I wrote columns for his venture Brownstoner Queens for awhile, a spinoff from his successful real estate website, Brownstoner. Butler sold it for what I presume is a bundle a couple of years ago and it has passed through a couple of owners since then.

The name comes from the representation of Bergen Street formerly found on enamel signs on the station pillars of the Bergen street station serving F and G trains a few miles west in Carroll Gardens. Those signs were replaced in the 1980s.

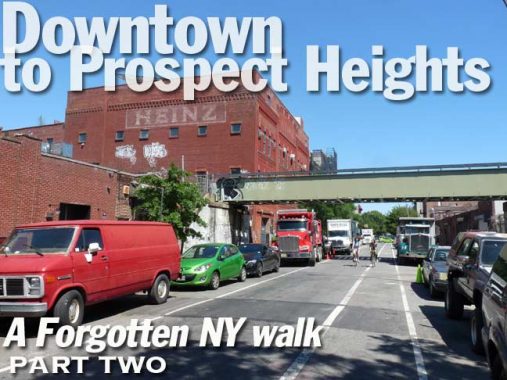

I am always drawn like flies on sherbet to the ancient brick Heinz food processing factory on Bergen Street right next to the Franklin Shuttle elevated section.

The factory, on which the company slogan “57 Varieties” is clearly still in view, was built in the late 1800s as part of a large brewery complex that extended to Franklin Avenue and around the corner to Dean Street. After Heinz decamped its building became the Monti Moving & Storage Co., which in turn moved out in 2001. The buildings are used by artists and light manufacturers these days, with the ice house on Dean has been converted to residential.

In the colonial era, this was a Hessian Camp, German mercenaries allied with the British. By 1849, even before much of the street grid had appeared, the Liberger and Walter Brewing company was brewing here, between 1866 and 1883 it was the Bedford Brewery run by Christian Goetz. In 1883, William Brown purchased the brewery, renaming it the Budweiser Brewing Company. After a suit by Anheuser-Busch in St. Louis, Brown changed the name to the Nassau Brewing Co. in 1902, and it continued brewing until 1914. Heinz then purchased the westernmost building and turned it into a factory.

The Franklin Shuttle, running past the old building, connects the IND Fulton Street Line with the Brighton Line at Prospect Park, and is all that remains of the northern end of the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island Railroad. In the 1970s and 1980s the city had no money for the line’s upkeep, and it deteriorated to the point of collapse, but in the late 1990s the MTA found some money in the kitty and completely rebuilt the shuttle, closing the Dean Street station but adding a transfer to the IRT at Eastern Parkway.

I haven’t posted on the Franklin Shuttle for awhile, but I should explore it in full once again. I got some shots of the Park Place station awhile back. In 2000 I did a fairly comprehensive history on this relic of the steam railroad days.

Looking north on Franklin Avenue, the spindly spire of 432 Park towers above the slanted roof of the Citibank/Citicorp/Citigroup Building (Lexington and 53rd) the former height champ from this vantage.

Time to kick it in the head for the day and head back to Penn Station, getting the C train at the Franklin Avenue station (unfortunately, the Franklin Shuttle transfers to a local train). The C train is still running several R-32 units that first rolled out in 1964.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

4/9/18