On the northern edge of Central Park, the hills are steep, and rough hewn staircases ascend as high as a two or three story building. This part of the park is known as the Cliff and is one of the natural aspects that the Park’s creators, Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, allowed to remain while building the park in the 1850s.

But part of what we’ll be looking at today is a great deal older than Central Park itself, and is a reminder that New York City faced threats from overseas in the 19th Century as in today’s troubled era.

The lampposts along Central Park North (part of West 110th Street) are like none others in the city. They were installed about 15 years ago as part of an improvement initiative formulated by the Department of Transportation and the Cityscape Institute, an organization founded by Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, who earlier had headed the Central Park Conservancy. Both organizations were concerned with the upkeep of infrastutcure, such as phone booths, trashcans on up to traffic control and streetlamps.

The 110th Street poles, with their sweeping, S-shaped arms, recall many of the streetlamps in Toronto, Ontario. It’s quite a departure from the usual found in NYC, which tends to come up with a design and stick with it for decades at a time. The poles haven’t found traction in other parts of town, though.

This was the first of two remaining working “Olive” stoplights I found in the park in the sumer of 2016. They originally held two-color Ruleta traffic signals. Unless I’ve been misinformed, the DOT just recently decommissioned the remaining Olives in Central Park (there were 5 or 6 working ones) and thus, the over 80-year reign of these stoplights has ended. It was fun standing next to one with a control box and hearing the inner workings chirp and clang while they were busy changing the light.

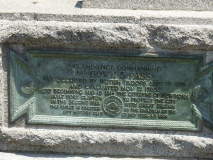

The War of 1812 blockhouse in the park’s northern reaches is one of my favorite real-life war relics. It was never used in anger, but was prepared in case of a British invasion.

In the United States’ second war with Great Britain, on August 9, 1814, a squadron of British war vessels, the HMS Ramilles, Pactolus, Nimrod, Dispatch and Terror, commanded by Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy approached Stonington, Connecticut. Hardy demanded that the town be evacuated and the British soon began the bombardment of the town.

The Americans’ response was led by Revolutionary veteran Capt. Jeremiah Holmes, who responded with cannon fire of his own. Though 40 houses in Stonington were damaged, not one American was lost, while the British took 20 casualties and 50 wounded. At length, Hardy fired one last full broadside and moved off down Long Island Sound. The Battle of Stonington was over.

The occasion of a British attack so close to New York City galvanized New Yorkers into action. Within days of the naval battle, a call went out for fortifications to be built; firemen, lawyers, members of the Master Butchers Association, the Sons of Erin, Columbia College students and others began digging trenches and building forts along the high ground in Manhattan. A chain of major batteries was installed in upper Manhattan: Fort Clinton, Fort Fish, a battery at McGown’s Pass, Nutter’s Battery, and Blockhouse Number One were in what would later become Central Park.

None of the batteries, fortunately, ever saw combat. The Treaty of Ghent was signed on Christmas Eve 1814, and the forts were abandoned almost overnight. (Andrew Jackson defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans on January 1815 before word of the treaty had reached the two opposing forces.)

For many years, the Blockhouse was in ruins, and a plaque commemorating its history was stolen (as most of them are). In recent years, the Blockhouse was stabilized and its flagpole repainted.

When it was built, the Blockhouse had a sunken roof with a large cannon that could be fired in any direction. The five fortifications in what would become Central Park had over 2000 militiamen garrisoned.

The other Olive stoplight along the East Drive, in all its unpainted glory. I wish the Department of Transportation would leave well enough alone and keep maintaining these rare stoplights, but perhaps the parts have to be jury-rigged and the agency doesn’t see the point anymore. Again, the oldest of these stoplights was installed over 80 years ago. They used to appear, two per most intersections, by the thousands.

![]()

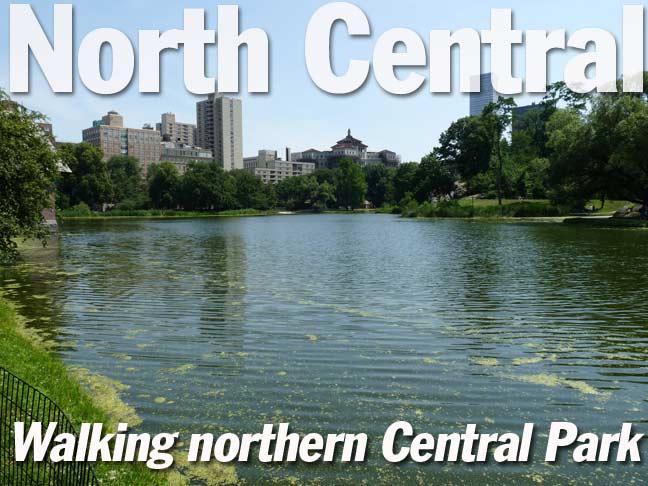

It looks quite natural today but Harlem Meer, named for a Dutch word for “small sea” (dark patches on the moon resembling bodies of water are called “meres”) was engineered by park creators Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux to replace a tidal marsh fed by Montayne’s Rivulet, which was retained. Today its water is piped in from the Central Park Reservoir and the pool reaches a depth of 4 to 8 feet.

![]()

To many observers, Huddlestone is the most remarkable Arch in the park. From some angles, it resembles a natural cave. It rests on neither mortar nor metal supports and is made of immense natural boulders, some of which weigh up to 20 tons, or 40,000 pounds. It has withstood traffic from horses and buggies on up to the SUV era and carries the East Drive. It was constructed in 1866 by Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould.

Mould designed the ornamentation at Terrace Bridge, the plazas at Bow Bridge, the Ladies’ Pavilion on the west side of the park, and the Central Park Music stand, Belvedere Castle, and the carvings and mouldings at Bethesda Fountain.

He was born in Kent, England and became an architect at an early age. He co-designed the “Turkish Chamber” of Buckingham Palace, worked on the Crystal Palace in Manhattan. Late in his career he designed the Morningside Park promenade in 1883 and a temporary tomb for Ulysses S. Grant in Riverside Park, which was later supplanted by the present memorial.

Mould was also a pianist, organist, and a translator of librettos from Italian to English.

Montayne’s Rivulet is actually a natural spring that was redirected to form a watercourse by Olmsted and Vaux. It originally crossed 5th Avenue and emptied into the East River.

The Ravine and Loch were reconstituted in 1993. Before that they had been choked with silt from the surrounding woods and taken over by non-native plants. Horticulturists subsequently planted red maples, sweet gum trees, tupelos and tulips along the Loch banks, as well as ostrich ferns and skunk cabbage.

The Andrew H. Green Memorial Bench, near East Drive west of the Conservatory Garden, is a memorial to lawyer and preservationist Andrew H. Green (1820-1903), who in large part is responsible, in his capacity on the fledgling Central Park Board of Commissioners, for the Olmsted-Vaux Central Park plan being effected. He also played an important role in the formation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, the Central Park Menagerie (the Zoo), and the New York Public Library.

After stints as President of the Board of Education and as NYC Comptroller, Green helped draft the Consolidation Law, in which unincorporated areas and municipalities of southern Westchester (the Bronx), Kings (Brooklyn), Queens, and Richmond (Staten Island) counties be consolidated with Manhattan to form the five boroughs of a greater New York City. The law took effect Jaunuary 1, 1898.

Tragically, Green was shot and killed by a deranged gunman in 1903. In 1929, this bench, along with five newly planted trees, were dedicated to Green. The bench was moved to its present location in the early 1980s. I’m not sure Green would approve of this location…it’s located quite close to the Central Park composting area and the stench is palpable even in midwinter.

Just north of the bench is the site of another War of 1812 fortification site.

Anticipating a British invasion, over 200 American volunteers hastily rebuilt the network of military fortifications over six weeks. Among the buildings was Fort Fish, named after the chairman of the City’s Committee of Defense. Positioned on the highest of the bluffs, it was the largest and most heavily armed of the forts. The others were Nutter’s Battery and Fort Clinton.

This overlook north of The Fort Fish site, across East Drive facing Harlem Meer, was the site of Nutter’s Battery, another War of 1812 fortification. It was originally a British Revolutionary War stronghold as it offers clear views north and west, and local militia rebuilt the site when there was anticipation of a British invasion in 1812. The battery was named for a local landowner, Valentine Nutter. It was the third leg in a trio of forts that included Fort Fish and fort Clinton (see below).

Originally inaccessible to the public, the site was paved and a low stone wall and benches were added in 1945. These items were restored, and new plantings were added, in 2014.

McGown’s Pass, to Nutter’s Battery’s immediate east, was named for a tavern run by Scotswoman Catherine McGown and her descendants from 1759 into the 1840s. (The tavern was on an old Manhattan road called Old Harlem Road; no trace of it remains, but a road it intersected, Harlem Lane, is today called St. Nicholas Avenue above Central Park from 110th Street north). The pass, located about midway on the southern edge of what would become Harlem Meer, was occupied by the British and Hessian mercenaries in 1776 and held until the end of the war in 1783. McGown’s Tavern, which was located south of the pass, was purchased by the Sisters of Charity in 1847 and became a religious community center called Mount St. Vincent. The Sisters decamped to Riverdale in the Bronx in 1860, and the site once again became a tavern and renamed once again for McGown. It was razed in 1917.

![]()

Fort Clinton, just to the southeast of Nutter’s Battery, was another British fort that was used by local militia prior to the War of 1812. It was named for DeWitt Clinton, in 1812 mayor of New York. Clinton, whose work paved the way for the construction of the Erie Canal, held most major elected and unelected offices in the NYC area in the early 19th Century.

Two cannons can be found at the fort site. They are not originals to the site, but were salvaged from the wreckage of Bristish ship HMS Hussar, which sank, purportedly with a hold full of gold, at Hell gate in 1780. The gold was not salvaged but the cannons were. Olmsted and Vaux placed them at the fort site when the park was designed in the 1850s.

The cannons were abandoned in the ate 20th Century and vandals did their relentless work. They were put in storage, but were replaced as part of the area renovations in 2014.

The Conservatory Garden, entered by the Vanderbilt Gate at 5th Avenue and East 105th or by park paths to its west, is Central Park’s only meticulously maintained formal garden. Colorful plantings are arranged in concentric circles around the Three Dancing Maidens fountain. Tulips abound in spring’ ‘mums in fall.

The Maidens fountain is a recast of an original fountain found in Berlin, Germany sculpted in 1910. The recast was acquired by Samuel Untermyer and was installed at his estate in Yonkers. Upon his death in 1947, his family donated it to Central Park.

The Garden’s Vanderbilt Gate at 5th Avenue and East 105th once protected the mansion of Cornelius Vanderbilt II at 5th Avenue and 58th Street. It was made in France but designed by American George W. Post. It was donated to the city by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, founder of the Whitney Museum which recently relocated downtown next to the High Line.

I can’t resist showing a Donald Deskey post at 5th Avenue and East 106th Street. First introduced in 1958, they appeared by the thousands both on regular streets and expressways, but as parts became scarce, they have been gradually grandfathered out. This one still has its original fire alarm indicator fixture. Unfortunately these were inexpertly designed and many of the covers have to be held on by tape. It doesn’t matter, since none of them work anymore.

Though it looks 100 years older this is the newest major building in Central Park. It was built in 1993 just west of Duke Ellington Square at 5th Avenue at 110th Street as a visitor center offers a wide variety of free education and community programs, seasonal exhibits, and holiday celebrations.

Perched on the northern shore of the Harlem Meer, the Dana Center is Central Park’s newest building, and the first to be built specifically as a visitor center. Adjacent to the Center is a small plaza, where many community programs take place. These include the Harlem Meer Performance Festival in summer, the Halloween Parade and Pumpkin Flotilla in autumn, and the annual Holiday Lighting event in winter.

Charles A. Dana Jr. (1915-2001) was an industrialist and philanthropist.

Please help contribute to a new Forgotten NY website

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

11/11/18

6 comments

My guess is that the City is getting pressure from the Fed DOT requiring a amber signal sequence on replacement traffic signals.

I have never been to the northern part of CP but it looks like there is a lot to take in. Great read.

I adore your work, always have, please never stop.

This sculpture is far more offensive than the one they removed in Kew gardens. Those who vendor stuff should go after these female statues.

Until that Forgotten NY of that area, this was a part of Central Park I pretty much never been to.

The New York City Parks Department oversees Central Park’s signal system, not the DOT. That said, the once prevalent two-color (red and green) traffic signals that controlled crosswalks throughout the park survived for years, even after the last two-color traffic signals under NYCDOT jurisdiction succumbed to removal in 2006 in Queens. It may be possible outside influences helped to shape the modernization process throughout Central Park in the past decade. As of 2019, it was confirmed at least one signalized crosswalk still had two-color traffic signals in use, but I imagine its days are reduced. Mostly all other configurations have been gone to history for the past several years now.