Forgotten New York’s Inwood and Marble Hill tour was so successful this past June (2019) I thought I’d recap it here…

Inwood was the last part of Manhattan to develop along the lines of neighborhoods to the south. During the Revolutionary War, colonials erected Fort Cox, or Fort Cocks, overlooking the Hudson River. After independence was attained, for the next century and a half, Inwood Hill Park was occupied by a variety of country mansions including the home of department store magnate Isidor Straus and his wife Ida, who lost their lives in the Titanic disaster.

A system of winding roads traversed the hilly ground. Some of them now describe park paths in the vast Inwood Hill Park. The City took title to this territory in 1916 and gradually, for the next 25 years, Inwood Hill Park as we know it was developed. The park includes a salt marsh and ‘virgin’ forest left over from the pre-colonial period. Except for some historic farm remnants shown below, Inwood was mostly developed in the first 2 decades of the 20th Century.

GOOGLE MAP: INWOOD AND MARBLE HILL

East of the elevated Dyckman Street IRT #1 train station, Dyckman Street continues southeast along the northern end of High Bridge Park, one of the longest north-south parks on the island (though nowhere close to matching Riverside Park). It’s no slouch, though, running approximately 45 blocks between West 155th Street and Dyckman. The south side of Dyckman Street is marked by huge outcroppings of Manhattan schist rock, which is common in northern Manhattan and the Bronx. The large boulders were deposited by a glacier, which got as far south as the middle of Long Island at its biggest before retreating some 10,000 years ago. In some cases, these rocks were dynamited out of the way of the street rid, and in other cases, they serve as bedrock for apartment houses.

Swindler Cove Park, east of 10th Avenue where it meets the Harlem River Driveway and Dyckman Street, is a recent addition to the Sherman Creek public area, found south of the creek along the mighty Harlem and east of the Harlem River Drive.

From 1996 to 1999, NYRP removed tons of garbage, rusted-out cars, sunken boats and construction debris from this waterfront site. Then, in 1999 – in partnership with the State of New York Department of Transportation and acclaimed landscape designer Billie Cohen – NYRP transformed the land into a lush array of restored woodlands, wetlands, native plantings and a freshwater pond, accented by a gracious pathway.

When I was just starting out FNY when the world was young, ForgottenFan Jon Halabi tipped me off to Sherman Creek, which was marked “marina” on a then-current Hagstrom map. What we found was a yacht graveyard full of discarded ketches and pleasure boats. The spot marked “marina” on the old map is currently occupied by a massive Con Ed substation on Academy Street east of 10th, which in fact has been made even more massive the last couple of years.

Looking east on West 202nd Street from 10th Avenue, the dome of the Hall of Fame for Great Americans can be seen across the Harlem River.

The president of New York University, Cornelius McCracken, on one of the highest points in the Bronx, from which there are spectacular views of Manhattan and beyond, the Palisades of New Jersey. Built The Hall of Fame for Great Americans in the fields of government, science and the arts. He hired the brilliant design firm of McKim, Mead and White to build a tribute to the great men (and a few women) and call it the Hall Of Fame For Great Americans, which opened in 1902.

The NYU campus in the Bronx has since become Bronx Community College but the Hall remains.

In 2017, Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee’s busts were removed during a flurry of controversy regarding Confederate memorials. The Hall is in serious need of repair, but the costs are estimated at $12M, well beyond the budget of BCC.

When the Dyckman Houses, which occupy the triangle between Dyckman Street and 10th and Nagle Avenues opened in 1951, Elouise Carrington Whitehurst was among the first residents. She remained for over 40 years, becoming largely responsible for the Houses’ upkeep.

The side wall of Washington Heights Academy, West 204th and Sherman Avenue, depicts a giant tulip tree that once stood at a historic crossroads we will see later in the tour. Tulip trees are along the tallest and straightest trees that grow along the east coast and were used by Native Americans in the precolonial era to make boats. The artwork was produced in 2011 by Wennie Huang and Michael Imlay.

Mount Washington Presbyterian Church is the “new” building of the oldest congregation in Inwood, established in 1844 by Samuel Thomson. Led by the Rev. George Shipman Payson from 1874 to 1920, the church served early families of Inwood, including the Dyckmans, the Ishams and the Vermilyeas.

The church bears the date 1928 as the present church was begun in that year by Renwick, Aspinwall & Guard, while the parish house dates to 1914. George Shipman Payson was a relative of Charles Shipman Payson, who owned the New York Mets after the death of his wife Joan Whitney, selling the team to Nelson Doubleday and partner Fred Wilpon in 1980.

This 1913 vintage fire alarm still sports the shaft and the fixture that once held a red glass indicator light. The red glass was later replaced with orange plastic, and later, all indicator lamps were lamppost mounted.

The historical centerpiece of Inwood is the Dyckman Farmhouse at Broadway and West 204th Street, which has been here since about 1785 and is Manhattan’s last remaining Colonial farmhouse. It was built by William Dyckman, grandson of Jan Dyckman, who first arrived in the area from Holland in the 1600s. During the Revolutionary War the British took over the original Jan Dyckman farmhouse; when they withdrew at the war’s end in 1783 they burned it down, perhaps out of spite.

The farmhouse was rebuilt the next year, and the front and back porches were added about 1825; the Dyckman family sold the house in the 1870s and it served a number of purposes, among them roadside lodging. The house was again threatened with demolition in 1915, but it was purchased by Dyckman descendants and appointed with period objects and heirlooms. It is currently run by New York City Parks Department and the Historic House Trust as a museum. A copy of one of the occupying Hessian soldiers’ log huts, with a log roof, can be found at the back of the house.

An old name, recently revived somewhat, for Inwood between Broadway and the Hudson River along Dyckman Street is Tubby Hook, possibly named for a 16th-Century Dyckman in-law Peter Ubrecht.

The first Good Shepherd Catholic church was a wood frame building that was moved across Cooper Street around 1930 and later razed to make way for an addition to the elementary school.

When the IND subway reached Inwood in the early 1930s, the population increased, necessitating a bigger church, and the present Romanesque church was built on Broadway and Isham Street in 1935 from Fordham gneiss mined in Manhattan and Bronx quarries. Originally established to minister to Inwood’s Irish community, the Church of the Good Shepherd of today with the aid of the Capuchin Franciscan Friars, Province of St. Mary serves a largely Hispanic congregation.

What could be one of the two last gaslight posts on public Manhattan streets can be found here, at Broadway and West 211th Street. The other one is on Patchin Place in Greenwich Village. However, old photos reveal that these posts, in addition to holding gaslight fixtures, could also carry street signs and mailboxes. The only older photos I have reveal street signs on this post. However, gaslamps have not been commonly used on NYC streets since the early 1910s, so this pole may have originally carried a gaslamp and later, street signage.

Part of an old neon sign has been revealed behind a tore sign at Broadway and Isham Street.

Like other parks in northern Manhattan, the site of Isham Park played a crucial role in the battle of Fort Washington during the American Revolution. The site served as a landing point for Hessian troops coming up the Harlem River to drive the American forces to Westchester and New Jersey.

In 1864 William B. Isham, a wealthy leather merchant, purchased twenty-four acres along the Kingsbridge Road, now known as Broadway, from 211th Street to 214th Street, and northwest to Spuyten Duyvil Creek.

The park originally included the old Isham mansion, stables, and green house, with the mansion located at the summit of the hill. The park attained its present size in 1927 after Isham family donations and other land purchases. The mansion was razed in 1940.

The Boston Post Road, which followed an already established Native American trail, was established in 1673 as couriers bringing mail to different locales in the colonies traveled the trail, which was then very rough and interrupted in several locations.

After nearly a century, the road was straightened and improved somewhat between New York and Boston, and from 1753-1769 heavy stone markers were set at one-mile intervals, with the surveying supervised by Benjamin Franklin. Postal rates were set by the distances between one spot and the other. Did “Poor Richard” handle this 12-mile marker, now embedded in the Isham Park wall? Perhaps he did.

At some locations in upper Manhattan and the Bronx, streets are laid out and mapped, but are too steep for vehicular traffic, originally horses and carts and now cars and trucks. In such cases the streets were built as steps, for pedestrian traffic only. That’s what happened here at West 214th Street at Seaman Avenue at Isham Park. Seaman Avenue, named for a family that owned property in Inwood in the colonial era, splits between Inwood Hill and Isham Parks.

As natural as some parts of Central Park look, every square inch of Central Park was originated on the planning boards of planners Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. Inwood Hill Park is 196 acres of primordial forest (with the occasional path and rusting park lamppost). It was the site of Native American habitation; deer and raccoon were hunted for food and clothing. After the Civil War, prominent families built large mansions here overlooking the Hudson, among them Isidor Straus, who perished aboard the Titanic in 1912, and the Lord family of Lord & Taylor. The area officially became a park in 1926.

Inwood Hill Park contains the last remnant of the tidal marshes that once surrounded Manhattan Island. The marsh receives a mixture of freshwater flowing from the upper Hudson River and saltwater from the ocean’s tides. The mix of salt and fresh waters, called brackish water, has created an environment unique in the city and the marsh contains wildlife such as fiddler crab and ribbed mussel developed a dependent relationship with the cordgrass that colonized it.

The arched Henry Hudson Bridge, opened in 1936 to bring the Henry Hudson Parkway across the Harlem River, can be seen from the park.

Supposedly, Shorakkapock Rock is the site of one of the greatest, or worst, real estate swindles in history, depending on your point of view. In 1626, the story goes, Dutch governor Peter Minuit purchased Manhattan Island here from the Weekquaeskeeks, or possibly the Canarsie or Lenape, for a collection of beads and trinkets valued at 60 Dutch guilders. Minuit is remembered by a plaza at Whitehall and South Streets all the way downtown. The situation may not have been as cut-and-dried as that, though.

The memorial is in place of a giant tulip tree where the transaction took place. The tree was planted by the Lenape shortly thereafter and it remained in place until 1933.

“Shorakkapock” has a number of variant spellings. In a shortened form, it turns up as “Kappock Street” in Spuyten Duyvil, Bronx, where it’s pronounced KAY-pock.

Just past the Rock, the path leads you along the hill. You will see rock formations that were dragged here by the Wisconsin Ice Sheet during the last ice age. Native rocks like this are visible in many areas in Manhattan and the Bronx, but are especially noticeable in Inwood Hill and nearby Fort Tryon and High Bridge Parks. In the natural hollows formed by the rocks, the Lenape found shelter, cooking clams and oysters. In the past, pottery artifacts have been found in these crevices.

This is the 4th Broadway Bridge spanning the Harlem River, replacing earlier ones constructed in 1895, 1905, and 1908. The 1905 bridge was floated about a mile south and is presently the University Heights Bridge. The current bridge is a lift bridge that can be raised to allow ship traffic to pass below on the Harlem River, opened in 1962.

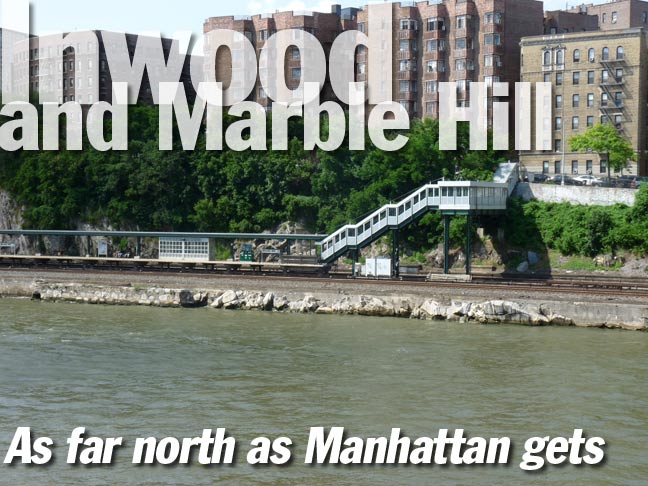

The Harlem River is seen here from the Broadway Bridge, with the Metro-North Marble Hill station. The river divides the borough of Manhattan from…the borough of Manhattan. The story of how that came about is a convoluted one.

In a little-known quirk of geography, a small piece of the borough of Manhattan, known as Marble Hill, is on the mainland. It is surrounded on three sides by the Bronx and on the south by the Harlem River. It shares its character with the neighborhoods of Kingsbridge and Kingsbridge Heights on its north and east. It is protected from Spuyten Duyvil, on the west, by a steep hill.

In 1895 it was separated from the island by the newly straightened, dredged and deepened Harlem River Ship Canal, leaving Marble Hill as an island itself. When, in about 1917, the creek was filled, Marble Hill became a part of the mainland!

No one cared much until the el was built through Marble Hill and apartment buildings were constructed in the 1920s, joining the few frame houses that were already there. Marble Hill never changed its designation as part of Manhattan, and so a part of Manhattan it stays, separated from the rest of the borough by the Harlem River.

Though Marble Hill has its share of handsome Manhattan-style apartment buildings, including one on West 225th Street that has windows specifically angled to catch morning sunlight…

Marble Hill features in large part a number of single-family homes on their own plots, par for the course in the other four boroughs, but quite unusual in Manhattan.

A 1920s-era building features terra cotta urns at the roofline.

The oldest building remaining in Marble Hill is likely St. Stephen’s Methodist Episcopal Church, which as the cornerstone says, was built in 1897 (Alexander McMillan Welch). The congregation dates to 1826 in what would be the Mosholu Parkway area, moving to Riverdale in 1876.

The longtime pastor (1946-1977) of St. Stephen’s, Dr. William A. Tieck, was also a Bronx historian and founder of the Kingsbridge Historical Society. He wrote several historical books about the Bronx, including Riverdale, Kingsbridge Spuyten Duyvil, New York City, A Historical Epitome of the Northwest Bronx. He preceded Lloyd Ultan as the official Bronx County Historian.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

8/25/19

10 comments

I’ve heard that the Hall of Fame isn’t open to visitors, even thought the BCC site says it is. Gate security turns people away.

I’ve always gotten in. However the guards are Nazi about photographers on the BCC campus.

Every other year or so Open House New York does a tour of BCC- Not only the McKim Meade and White buildings that create the original NYU Quad- but the Marcel Bruer buildings as well-

Hall of Fame is really called the Gould Memorial Library, commissioned by the daughter of Jay Gould. In 2012 a new library was built by Robert Stern, AIA to the design and specifications of McKim Meade and White (using modern equivalents)

Hey Kevin,

Was at your event in Astoria a few weeks back, great stuff, hope to do one of the tours these days. Do you know of any areas with Single-Family homes in Manhattan (on the island- besides Marble Hill)? Not including like museums or city preserved ones. I’m assuming there’s probably a couple way uptown but they are probably super rare.

As to single-family homes in Manhattan, the first that comes to mind would be W 217 St between Park Terrace East and Park Terrace West in Inwood. Detached, with front yards and driveways. Also the adjacent part of Park terrace West. Another is the block of Wadsworth Ave between 187 and 188 in Washington Heights, although some may have been converted to apartments. A possible runner up might be the Landmarked Astor Row (W 130 St between 5th and Lenox) in Harlem; not exactly detached, but “double” houses in the Philadelphia style. Front and side yards, nice porches.

I’m sure there are others.

If you took pictures of some of those sites in Inwood including Fort Tryon Park and the Cloisters without showing the surrounding area, it could almost make you think that it wasn’t Manhattan despite being on the upper tip of the very borough.

Two comments:

First, the NYU Bronx campus was sold in 1973 to CUNY, which turned it into Bronx Community College. I graduated from NYU’s Bronx campus a few years prior, and remember the view from the University Heights campus, as it was known at the time, across the Harlem River. The NYU campus is located at 181st St. in The Bronx, opposite 202nd Street in Manhattan. The East-West street number grids in The Bronx begin as roughly the same (132nd St. in The Bronx, the southernmost street, is almost opposite its Manhattan namesake street), but at Manhattan’s 202nd Street is about twenty blocks higher than the corresponding numbers across the river. This is because the hilly and uneven Bronx topography causes the north-south block lengths to be longer than the standard 200 feet on the Manhattan street grid.

Second, the current Broadway Bridge was assembled offsite and moved into place over 3 days on the Christmas weekend in 1960. The old bridge was cut away and the new one moved in. Amazingly, the IRT #1 service was only suspended for a few days. Roadway traffic resumed within a month. Only the moveable roadway span was initially available, of course fixed in place originally. The towers for the lift span were built while the moveable part was already in use. It was fine example of precise engineering work, long forgotten. From the NYU campus, the towers of the Broadway were easily visible as long as the weather was clear.

I was looking at a Bronx map from 1900, and it shows 129 Street used to be the southern most. 129 & 130 Streets were one block long.

Your source regarding the Tubby Hook/Inwood Hill mansions is open to doubt: “After the Civil War, prominent families built large mansions here overlooking the Hudson, among them Isidor Straus, who perished aboard the Titanic in 1912, and the Lord family of Lord & Taylor.” (Alas, I’ve seen misinformation similar to the foregoing quotation in Wikipedia.) Below are some clarifications.

First, many of the mansions to which you refer were built before the Civil War. For example, Samuel Boyd Thomson’s “Mount Washington,” the first mansion erected on the hill, was completed more than 25 years before the start of the Civil War.

Second, Isidor Straus did not build his Inwood Hill mansion. Rather, he purchased the existing Francis Augustus Thompson villa. (It was constructed in the mid 1850s, when Master Straus was roughly ten years old.)

Third, though I’ve read the apocryphal story about the Lord family in several places, I haven’t found any official records to substantiate the assertion that the Lords ever owned a mansion in Tubby Hook/Inwood. I hope you see fit to excise the erroneous reference to the Lords, Kevin.

Correction to my comment: “the first mansion erected on the hill, was completed more than 25 years before the start of the Civil War” should be emended to “20 years before the start of the Civil War.”