Continued from Part 1: Fort Wadsworth and Clifton

In 2019, I made three separate pilgrimages and Walks of Penance in Fort Wadsworth, Rosebank and Clifton areas on the east shore of Staten Island. The first was on January 1 and the other two were in late spring, May and June. On the third I was accompanied by over a dozen people since that was an actual Forgotten NY tour I was doing; the first two trips were “scouting missions.” I’ve visited Clifton and Rosebank on numerous occasions, and even took a room in a bed & breakfast on Hylan Boulevard and Edgewater Street for a week in February 2005 to easily get the photos I would need for the Staten Island listings in Forgotten New York the Book, published in September 2006. Of course, every time I visit, I find something new.

My January 1 visit was during a period in which the government had run out of money and basically, everything was shut down, including the Fort Wadsworth visitor’s office. I wanted to ask the park rangers if group tours not conducted by park personnel were permitted. When I visited again in May the rangers assured me they were, and one even accompanied us: I’ll get to that in just a bit.

My walks took me to different locales while in the end, depositing me on Bay Street where I could get a bus back to the ferry. Thus, I’ll be posting images on several different pages. Here, I’ll concentrate on the May walk, which was the longest, and I’ll make it a multiparter to prevent wearing me, the writer and you, the reader, out. By the way, after the tour in June 2019, the postgame show was held at J’s on the Bay, 1189 Bay Street off Hylan: we always seem to end up at diners and here, the food is good and the decor consists of chrome, red and white, which is just fine with me. Of course, dining in isn’t an option during the Covid Crisis.

I miss doing the physical tours and am working on using Zoom and Powerpoint to do virtual ones. If I master it, it’ll be a year-round option.

GOOGLE MAP: FORT WADSWORTH & ROSEBANK

Shaughnessy Lane

Shaughnessy Lane runs for one block, from White Plains to Tompkins, north of St. Mary’s. It’s longer than Kaltenmeier Lane, from Part 1, but matches it with 11 letters. It’s really a slice of small town life, even more than usual in Staten Island. A look at Shaughnessy Lane in 1940 does not reveal much of a difference between then and now.

Garibaldi-Meucci Museum

Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882) crusaded for a united Italy in the early to middle years of the 19th Century. In 1834 he joined Giuseppe Mazzini in the Young Italy Society; after an unsuccessful uprising in Genoa in 1836, he fought in South American wars of liberation, using what today would be called guerrilla tactics. After a sojourn in the USA in the 1850s he organized and led insurgencies leading to conquests of Sicily and Naples which ultimately produced the unification of Italy in 1860 under King Victor Emmanuel II.

Garibaldi resided in the USA, with his friend, Antonio Meucci, from 1851-53 in a house owned by musician Max Maretzek. Meucci was the inventor of the telephone as far back as the 1850s (Alexander Graham Bell, who everyone considers the inventor, was able to obtain a patent for the device before Meucci could afford one).

Meucci was born in Florence, Italy in 1808. He studied chemical and mechanical engineering at the Florence Academy of Fine Arts and had designed an acoustic version of a telephone as early as 1834, the year he ws imprisoned on suspicion of being involved with the Italian unification movement, with which he was sympathetic. In 1835 he journeyed to the Americas, stopping in Havana, Cuba long enough to construct a system for water purification and restoring Havana’s Grand Theatre.

While still in Cuba in 1849 Meucci developed the first of the devices that could be said to work like the modern telephone; and in 1850, he and his wife, Ester, moved to the house you see above, in Clifton, Staten Island. Between 1856 and 1870 Meucci produced more than 30 telephones employing electromagnetism. Funding for his invention was hard to come by; Italy was inflamed in revolution, led by his friend, Garibaldi. Meucci was then struck by a series of bad breaks as he was left bankrupt by debtors. A series of court cases in which Meucci attempted to sue Bell for patent infringement were ultimately unsuccessful and the last case was dropped upon Meucci’s death in 1882.

In 1907 Meucci’s residence was moved to its present location at 420 Tompkins Avenue and Chestnut Avenue; between that year and the 1950s, the house was overwhelmed by a pantheon with classical pediments and columns erected by the Garibaldi Society proclaiming the house as the Garibaldi Memorial. That seemed to be the modest inventor’s fate: stymied by Bell in life, and overshadowed by Garibaldi in death! The liberator, during his time on Staten Island, worked as a candlemaker in Meucci’s factory and fished in the island’s many lakes.

Since 1956 the Order of the Sons of Italy has maintained the house as a museum, open to the public. The museum contains many letters and photographs documenting the lives of the inventor and the revolutionary, examples of Meucci’s handmade furniture, and a library of rare and out-of-print books. The stele honoring Meucci has four friezes with frolicking couples; what that has to do with radio, you can try and guess. Contact the Museum at (718) 442-1608, though it’s likely shut for the remainder of the Covid Crisis.

Meucci is also honored by a monument in Gravesend at Avenue U, 86th Street and West 12th Street.

Clifton

Clifton is a Staten Island neighborhood flanked by Rosebank on the south and Stepleton on the north, neatly separated from Rosebank by the Staten Island Railway and perhaps less neatly from Stapleton by the Stapleton Houses and campus of Bayley-Seton Hospital. The genesis of the name is unclear, but Clifton does happen to be in the shadows of NYC’s highest hills: the moraine made up of Wards, Grymes, Emerson and Todt Hill, though there are no obvious cliffs.

I’ve always been fascinated by American Self-Storage, at Tompkins and Greenfield Avenues, the former DeJonge paper factory.

Tompkins Avenue is bridged over both Greenfield Avenue and an active branch of the Staten Island Railway, and a pedestrian stair still possessing its ancient iron railings connects the two avenues.

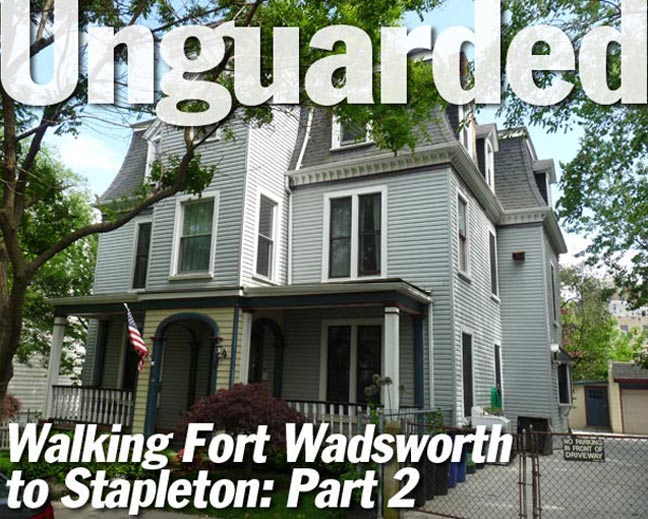

Townsend Avenue was originally the driveway leading to the estate of brothers James, Charles and William Townsend, who built a Gothic Revival castle in the center of the plot in the 1840s. In the 1850s, land along the driveway was subdivided into plots and in the latter half of the century a collection of other Gothic Revival and Queen Anne style homes was built up and down the street. Unfortunately in the past two decades, many of these have disappeared as developers have erected generic multi-family homes they have deemed more suitable for the region in the early 2000s. A few do remain, though, such as the one on the north side of the avenue near Tompkins.

Adventures in Vandyland

Clifton, Staten Island, has always been associated with the Vanderbilt family; its scion Cornelius operated a ferry to Manhattan beginning in 1810 at age 16, and its main east-west drag is Vanderbilt Avenue, which continues south into the heart of the island as Richmond Road.

I’m fascinated with the Tudors along Vanderbilt. I’ve talked about them before, but not for awhile.

In 1900, the firm of Carrere and Hastings built eight houses along the family’s namesake avenue, from 110 to 144, between Talbot Place and Tompkins Avenue for George Vanderbilt in 1900. Other houses were built for Vanderbilt on neighboring Norwood Avenue; additional mansions were found on nearby Townsend Avenue, but many of them have been lost to redevelopment.

The Staten Island branch of New York Foundling is on the Bayley-Seton Hospital grounds on Tompkins Avenue west of Vanderbilt. It’s one of NYC’s oldest child welfare agencies:

In 1869, three Sisters of Charity opened their doors to save the lives of babies being abandoned on the streets of New York, beginning the tremendous legacy of the New York Foundling. Over the past 150 years, the Sisters’ ministry has continued evolving from a respite home for abandoned children, to a comprehensive spectrum of community support services

designed to provide opportunities to the children and families of New York. While social situations and our approach to our mission have evolved, we continue to share our founders’ belief that no one should ever be abandoned, and that all children deserve the right to grow up in loving and stable environments. [New York Foundling]

Bayley Seton Hospital

Bayley Seton Hospital at once presents one of NYC’s greatest historical opportunites and one of its greatest wastes, as most of its campus is disused at present.

The grounds of BSH house Staten Island’s first hospital, an historic colonnaded structure built in the 1830s to serve ailing retired naval and merchant sailors, appropriately named “the Seamen’s Retreat.” Change came to the site in 1858 when a mob of 30-40 prominent locals attacked and burned down the Port of New York Quarantine Hospital, located a mile north of the Retreat. Though this horrific incident was incensed by an outbreak of yellow fever the locals blamed on the nearby hospital, flagrant racism was most likely a factor—recent immigrants made up the majority of the hospital’s population.

Some of the quarantine station’s services were transferred to areas of what is now Bayley Seton Hospital, and placed under the jurisdiction of the Marine Hospital Service, which by 1885 controlled the entire complex, and by 1902 had been renamed the US Public Health Service. In the 1930s, President Roosevelt started a campaign to revitalize The Public Health Service Hospitals, resulting in the construction of the main seven-story art-deco building and its offshoot Nurses’ Residence, a winged four-story structure on the southeast corner of the property. [Abandoned NYC]

When the Sisters of Charity acquired the hospital in 1980 its name became Bayley Seton, after Richard Bayley, the head of the former Tompkinsville Quarantine Hospital and his daughter, Elizabeth Ann Seton (1774-1821), the founder of the order and the first canonized American-born saint (in 1975). Born into the Anglican Church, Elizabeth was a convert to Catholicism after the death of her husband William Seton. Her grandfather, Rev. Richard Charleton, was a rector of St. Andrew’s Church in Richmondtown and is buried in its churchyard.

After 2000 Bayley Seton Hospital fell on hard times after the Sisters of Charity turned over operations to the Vincentians, who faced financial troubles. Subsequently in 2009 the Salvation Army acquired the hospital, closing 8 of its 12 campus buildings; the eight stand abandoned and subject to predation by the elements, similar to Seaview Hospital and the Farm Colony in mid-island.

I acquired more photos of the campus, but did not see a very small “no trespassing” sign at the Tompkins Avenue driveway. After about 5 minutes I was accosted by a peevish security guard who drove up and ordered my vacation of the property. I did manage to get him to accept my card, but promised him I wouldn’t publish photos of the grounds, and I’m as good as my word.

I have no idea why security guards and police officers fear photographers so much, but I suppose it’s a “control thing.”

Stapleton

From Forgotten New York The Book:

Stapleton and Clifton are two adjacent neighborhoods on Staten Island’s northeast coast along Upper New York Bay. The Vanderbilt family held much land here in the early 19th century; in 1836 Minthorne Tompkins (the son of Vice President Daniel Tompkins) and merchant William Staples established a ferry to Manhattan and founded the village at Bay and Water Streets. German immigrants built numerous breweries in the area in the 1800s including Bachmann, Bechtel, and Piels, whose brewery was in business on Staten Island until 1963.

Among the most notable and strangest aspects of Stapleton’s history was the presence of the National Football League, which fielded a team known as the Staten Island Stapletons here from 1929 through 1932. The Stapes were a semipro team founded by restaurateur Dan Blaine in 1915, who played halfback for the team until 1924. Over the following couple of seasons, the Stapes would play exhibitions against pro teams from the NFL and the 1920s version of the American Football League, and after they rolled up a 10-1-1 record in 1928, including a 3-1 record against NFL squads, the Stapes joined the NFL the next season. playing in tiny Thompson’s Stadium on Tompkins Avenue, a site now occupied by Stapleton Housing. Led by halfback Ken Strong, a New York University graduate, the Stapletons compiled a 14-22-9 record against NFL competition in four years. The Stapes played an exhibition schedule in 1933, with some games against NFL teams, before Blaine folded the team and Strong joined the New York Giants.

In addition, the famed rap group Wu-Tang Clan, who have rung up sales in the millions since the early 1990s, were founded in Stapleton Houses.

Stapleton is by turns picturesque and forbidding. The main business section along Bay Street can be sketchy, but Tappen Park, which contains the former town hall of Edgewater (the Staten Island town that contained Stapleton) is surrounded by classic architecture, such as the Staten Island Savings Bank at Water and Beech Streets. Stapleton Heights, along St. Paul’s and Marion Avenues, is a NYC Landmarked District encompassing a number of beautiful Queen Anne-style residences; a Forgotten NY tour visited one such home back in 2014.

Harrison Street

Harrison Street, often referred to as “The Nook,” was developed roughly between 1840 and 1900. It was named for Dr. John Talbot Harrison, one-term State Assemblyman and Chief Health Officer of the Quarantine Station in the nearby neighborhood of Tompkinsville, which was developed by Daniel D. Tompkins, the United States Vice President under James Monroe. It is a proposed NYC Landmarked District, and the Mud Lane Society for the Renaissance of Historic Stapleton hopes to push through landmarking through some local opposition.

Harrison Street is obscure and hard to find if you are not looking for it. It runs one block between Quinn and Brownell Streets, but it does not access Tompkins Avenue. Instead, from Tompkins Avenue walking ferryward, turn right on Tompkins Street (yes, Tompkins Avenue and Street intersect) then turn right on Quinn. Harrison is your first left from there.

On this short street you’ll find some of Staten Island’s finest architecture; but only one house on Harrison (and another on Brownell) are landmarked in what should really be a protected district.

92 Harrison, off Quinn, is difficult to see since it is surrounded by thick vegetation. It is a Greek Revival building constructed in 1854 for Richard Smith. It is one of ten houses built on the block before 1860. It is one of two landmarked homes in the area.

Since Harrison Street isn’t a landmarked district, individual descriptions of the eclectic homes on the block—some built as early as the 1840s—are hard to come by. I’ll show them here in a Gallery, to give you a good luck at them; some are of the Victorian “jewel box” genre that I admire. Remember, each of these homes is subject to predation by developers who may want to build multifamily housing or something they deem more appropriate for the 2020s.

SILive does have a description of #44 Harrison, an Italianate constructed in the 1850s by carpenter Adrian Post. Adrian and Peter Post, brothers and carpenters, also constructed other homes along Harrison Street, including #58 which has unfortunately been renovated in a style uncomplimentary from other homes on the street.

Some of Harrison Street’s bluestone sidewalks. These usually mark a neighborhood of considerable age.

For a short two-block street, Brownell Street boasts two Protestant churches, facing each other across Tompkins Street, First Presbyterian (which appears to be a private home converted to a church) and the Temple of Restoration with its stepped gables.

I noticed the two metal street signs at #26 Broad Street, corner of Brownell. To satisfy curiosity I looked up the building in the 1940 Municipal Archives and found them absent then. So, the signs aren’t as old as they appear.

I had walked from Lily Pond and Major Avenues through Fort Wadsworth, Rosebank, Clifton and Stapleton and before getting the bus back to the ferry, time to show some of the artwork at Bay and Broad Streets, some of which was commissioned by an Indian restaurant on the corner. I intend to return to Stapleton for another in-depth examination when the Covid crisis is over and I can ride trains and ferries again.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

5/17/20

4 comments

https://www.silive.com/news/2014/03/advance_historic_page_from_oct.html

Next time you visit Staten Island beware of the local vampires:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/What_We_Do_in_the_Shadows_(TV_series)

https://fxnow.fxnetworks.com/shows/what-we-do-in-the-shadows

The factory building (now storage) was DeJonge paper co. My understanding was they made special wrapping papers made to order.

The old Bayley Seton Hospital was used extensively as Arkham Asylum in the recent “Gotham” TV series.