By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

A great avenue deserves a great gateway and some of New York’s famous roads have iconic monuments or parks at their starting points. But most of the city’s lengthy roads do not have such markers at their starting and terminal points. Until 2020, the ten-mile Atlantic Avenue only had Brooklyn Bridge Park at its western end, while its eastern tip was a vacant lot underneath an elevated train trestle next to the Van Wyck Expressway.

In the summer of the coronavirus pandemic, city and state officials cut the ribbon on Gateway Park, an 8.6-acre green space that included a block-long extension of Atlantic Avenue in Jamaica, serving as a southern gateway to the neighborhood. For children who like trains, this park offers views of the JFK AirTrain and the Long Island Railroad.

Prior to the park’s construction, Atlantic Avenue ended abruptly at Van Wyck Expressway, with its traffic then narrowing into 94th Avenue as it entered Jamaica. With the expansion of the Jamaica station and construction of new buildings around it, community leaders sought to improve traffic flow and build a new park.

The empty lot on the corner of Van Wyck and 94th had been that way since 2001, when the parcel was used as a construction area for the city’s youngest elevated train line. Prior to that it was a meatpacking plant and truck parking lot. To alleviate traffic congestion, the plan sought to extend eastbound Atlantic Avenue for one block through this lot to 95th Avenue, where traffic can continue east towards Sutphin Boulevard. 94th Avenue would then become a westbound one-way. Six residences within this block were preserved with the park built around them.

Along with its ability to improve traffic flow and opening a green public space, Gateway Park features rain gardens, a naturalistic way of channeling runoff into the ground rather than the sewer system. The name choice is surprising as it can be confused with Gateway National Recreation Area five miles to the south. Without a doubt, I expect lawmakers to find a local civic figure worth honoring with a park renaming. It is simply a question of when, not if.

In contrast to my story on the post-millennial Chelsea Green in Manhattan, the site of Gateway Park does not have a rich history to it, so I looked at the surrounding blocks for inspiration. From the park, one can see a control tower on the Long Island Rail Road with a sloping roof. This is the Jay Tower that used to control switches on the western side of the massive station. Today the switches are controlled from the LIRR office building next to the station.

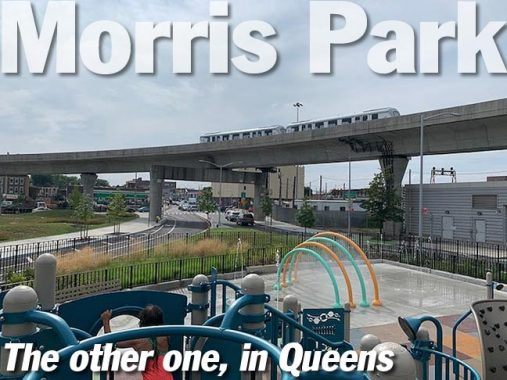

Facing the old tower is a train yard that had a freight station in the early 20th Century. This yard is used for train storage, part of the larger complex that includes Morris Park Yard on the other side of Van Wyck Expressway. The above image from the Municipal Archives looks east, with an empty lot on the site of Gateway Park.

Last year, Kevin Walsh documented a row of buildings a block to the south of here, noting that Van Wyck Expressway is usually associated with former mayor Robert Van Wyck, but in reality the highway’s route has a longer history as Van Wyck Avenue, named after a local family that shares his Dutch ancestry, but is not directly related to Mayor Van Wyck.

The same block today shows three of the four rowhouses from 1934 still having their pointed rooflines. Properties on the eastern side of Van Wyck Avenue were condemned in favor of the expressway, which opened in 1950.

Returning to 94th Avenue, at Liverpool Street is the sign with the honorific co-name “Sean Bell Way” in memory of the local resident killed by 46 police bullets on the evening before his wedding day. This year’s protests against police violence brought back memories of this incident. Bell was shot after leaving Kalua, a “gentleman’s” club that is today a Spanish-speaking Pentecostal church.

Kevin was on this block in 2014 to document the lengthy tunnels beneath the tracks leading into Jamaica station. On this note, I’ve been curious about the locked-up staircase at the 130th Street underpass that leads into Morris Park Yard. Was this an entrance to a long-shuttered LIRR Station?

Indeed, it was the Dunton station, named after LIRR President Frederick W. Dunton, whose name also appears on a street in Holliswood. This station was among the seven stations closed in 1939 when the Atlantic Branch was relocated beneath Atlantic Avenue. The stairs to the phantom station are reminiscent of those on the former Elmhurst station that Kevin documented in 2002.

A few feet before the westbound Atlantic Avenue train enters its tunnel, we have Boland’s Landing, a short employees-only station serving the Morris Park Yard. The yard was named after a section of Richmond Hill next to it. Its name was bestowed by Dunton in the 1880s in honor of a local landowner. The Morris Park of Queens should not be confused with Morris Park in the Bronx, which was named after an unrelated Morris. As is the case with Borough Park and Rego Park, neither of these Morris Parks has sizable park inside it. The namesake of Boland’s Landing was an LIRR engineer from many decades ago who worked here.

Morris Park was part of the Village of Richmond Hill, which has its own historical society to preserve the memory of its pre-1898 municipal independence. As is the case with Morrisania’s Town Hall, the site of Richmond Hill Village Hall is today a police precinct. The historical society affixed a plaque to the building to honor its past as a local seat of government. Following annexation by NYC, it hosted a courtroom, opera performance, and a police precinct. It was demolished in 1911, with the current precinct building completed in 1914.

The next phantom station on the westbound route is Morris Park, as seen in this 1934 photo. Reminiscent of the park facing the site of the College Point station, here we have the .21-acre Lt. Frank McConnell Park at the corner of Atlantic Avenue and Lefferts Boulevard. The official Parks Department description of this green space speaks of its namesake, the first Richmond Hill resident killed in World War I, and that the property was assigned to Parks in 1944. But its use as an open public space goes back to at least 1886, when the Morris Park station was built on this corner, with a spacious plaza facing the station.

The Morris Park station is gone, but the park adjoining the station hasn’t changed much since the last train departed. On the site of the eastbound platform is a bus stop on the Q24 route, which runs on Atlantic Avenue between East New York and Jamaica, serving communities that lost their train stations in 1939. There are no hints today of the next station to the west, Clarenceville, but continuing west is Woodhaven, which was abandoned in 1976 on account of low ridership. Kevin documented this station in 2015.

Across Lefferts Boulevard from the station and its park was the Morris Park Hotel, a cartoonish blend of Tudor, Gothic, and Victorian architecture that served passengers on the Atlantic Branch. The postcard is from the book on Richmond Hill by the late Nancy Cataldi and Carl Ballenas, unparalleled authorities on the history of the neighborhood. One looks at the grocery store on this corner today and the windows above it. Do they line up with the hotel’s window? Is this the same hotel building following a series of face-altering renovations, or an uninspiring replacement built after the train station was closed? Looking at nearby LIRR stations, Forest Hills and Kew Gardens also had upscale hotels next to the platforms. Today, the former is a residence and the latter is a senior home.

At the time of the station’s elimination, Robert Moses had unparalleled control over the city’s public works projects. Communities along Atlantic Avenue supported grade elimination for this railway, but not the elimination of stations along the route. Certainly the Jamaica Avenue El was nearby, but residents preferred the quicker railroad to downtown Brooklyn and Jamaica. When local Councilman Hugh Quinn requested the reopening of Morris Park station on the underground line in 1940, Moses argued that the entire grade elimination project would be delayed indefinitely. “If this happens you won’t see the elimination improvement in your lifetime.” Under Moses’ heavy hand, the underground line began running in 1942.

Another Morris Park curiosity is the school building behind St. Benedict Joseph Labre Church, named after the patron saint of the homeless. With Catholic school enrollment in decline, the building was used by the city as an annex for Richmond Hill High School and later as Epic North High School. Keeping with the separation of church and state, its old name and architectural crucifixes are covered up here.

The newcomer religion in Morris Park is Sikhism, representing mostly Indo-Caribbean and Indian immigrants. The Sikh Cultural Society has the largest temple of Sikhism in the city, properly called the gurdwara. This “neither Hindu nor Muslim” faith originated in the Punjab region straddling the border of India and Pakistan. The present facility replaces an older, smaller gurudwara that was a former Methodist church.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

8/2/20