Today’s post is ostensibly an examination of the signage of the IND (6th Avenue Line) portion of the 34th Street station, but I’ve also expanded it to include an examination of both Herald and Greeley Squares between West 32nd and 35th Streets, where 6th Avenue meets Broadway. In 2020, it’s been one of the murkiest Octobers in memory and while I prefer to take my “camera walks” in sunny weather… murk eliminates shadows, but doesn’t make for the pleasantest photos. Thus, I spent much of the brief walk I took shooting underground with my IPhone camera, using my Panasonic while outdoors.

Caution: some of this page will read like “Captain Obvious” to NYC residents, but I do want to explain subway nomenclature on this page to readers outside of NYC who may be a bit cloudy on the subway and its features.

Here’s one of the many entrances to the 34th Street station, which serves N/Q/R/W stations on the Broadway line (former BMT); B/D/F/M (former IND); and PATH trains. At one time, a corridor allowed a pedestrian (out of system) transfer to Penn Station, where Long Island Rail Road trains as well as to 7th Avenue lines, the 1, 2 and 3, former IRT lines. No one thinks about it much, but it’s one of the largest rapid transit junctions in the United States and is up there worldwide with passenger volumes in normal times.

The “big M” is a retired Metropolitan Transit Authority logo; it has since been replaced by the “Doppler” MTA logo. The former logo proved ideal for the square-shaped entrance stanchions and still appears many times around town.

The former McAlpin Hotel faces 6th Avenue at West 33rd. It was constructed in 1912, the year the Titanic went down, 2 years after Penn Station opened, and it was at the time the world’s largest hotel. It is presently called the Herald Towers and holds condominiums and retail on the ground floor. Its Marine Grill boasted several colorful terra cotta murals of maritime scenes. Thankfully they were saved and placed in the Fulton Street complex of subway stations downtown on Broadway.

Herald Square is named for a long-defunct newspaper, founded in 1835 by James Gordon Bennett Senior, who made it the most widely-read and profitable newspaper in the country. He ceded operations to his son James Gordon Bennett Junior in 1867, who continued the paper’s popularity while resorting to fabrication on occasion: the paper falsely reported in 1874 that the inhabitants of the Central Park Zoo had escaped and were causing a ruckus. The paper funded the famed African expedition of Henry Stanley to locate explorer David Livingstone. After Bennett’s death in 1924, the Herald was acquired by the New York Tribune. The Herald Tribune lasted until 1966 when a printers’ strike put it out of business.

In 1908 Bennett commissioned architect Stanford White to build the newspaper’s offices on West 35th, facing the square, which was then named for the newspaper. The ornate, Italianate building stood only until 1921.

However, there is still plenty of the old Herald building to see in Herald Square. The old building was crowned by a moving vignette of bronze statues sculpted by by Antonin Jean Carles: the Roman goddess Minerva and a bell struck on midday hours by two ringers who have, over the decades, acquired the names “Stuff” and Guff.” When the Herald building was razed in 1921, the vignette, after 19 years in storage, was placed, bells, Minerva, and ringers, in a large 40-foot tall granite stele after the 6th Avenue El had been razed (see below).

Minerva, the goddess of wisdom in the old Roman pagan beliefs, had a “spirit bird,” the owl, also perceived as a symbol of wisdom over the millennia. Bennett had several bronze owls displayed on the cornice of the Herald building along with Minerva and her bellringers, and two of the owls with outstretched wings appear on the stele. If you go by the monument at night, look for the owl’s eyes to blink green. There are a second pair of owls, with folded wings, at the Herald Square entrance north of West 34th.

There’s one more owl, embossed on the door on the back of the monument, with the French phrase “La nuit porte conseil” which means “Let’s sleep on it” as a hedge against rash action, which is usually good advice.

The Saks Building has been on the SW corner of Broadway/6th Avenue and West 34th in one form or another since 1902, when it opened a couple of weeks before rival Macy’s opened its doors. Unlike department stores Macy’s and Gimbel’s, Saks, founded by Baltimore merchant Andrew Saks, sold mostly clothing. Gimbels purchased Saks in 1923, but kept the name and rebranded it as Saks Fifth Avenue; since 2013 the chain has been owned by Hudson’s Bay.

The Saks Fifth Avenue occupying the original building closed in 1965 and Korvette’s, a discount chain (as opposed to Macy’s and Gimbel’s) moved in in 1967, which modified the exterior, stripping away most architectural detail introduced in 1902. When the building changed hands again and became the Herald Center, it underwent another renovation. The AIA Guide to New York City noted dryly in 2010: “A bulbous blue whale swallowed Buchman & Fox” meaning the original architects.

The R.H. Macy & Co. department store has held down the parallelogram between 6th and 7th Avenues and West 34th and 35th Streets since 1902, when the concern moved uptown from Ladies’ Mile at 6th and West 14th. The store’s history is well-known: founder Rowland Hussey Macy, who had served on a whaling ship and acquired a red star tattoo, opened general stores in 1851 in Haverhill, MA and in 1858 in New York City. which outgrew its original Ladies’ Mile location. Macy’s hired architecture firm De Lemos & Cordes to design its Midtown Herald Square flagship at 6th and West 34th, which included its original grand 34th Street entrance with the clock seen here. Additions in 1924 and 1928 expanded the building west to 7th Avenue; two small properties at 6th and 34th and 7th and 35th held out and were not acquired by Macy’s until decades later.

I was a Macy’s employee from April 2000-October 2004, working in the copywriting bullpen on the 17th floor on the 7th Avenue side. I was proud to work at the self-named World’s Largest Store but it was not an especially pleasant tenure; the person who hired me was eased into a different role a short time after I was hired, and the replacement supervisor took an immediate dislike, and whatever errors I made were magnified.

However, while I was there I took an immediate liking to the infrastructure. When I got the chance I would wander off onto the 17th floor ledge and got photos of the street below, and I would ride the original 1902 wooden escalators. For my lunch hour, I would rove all over midtown and into Central Park, and even took a train to downtown Brooklyn a few times, getting photos that made their way onto the website as well as Forgotten NY the Book in 2006.

It’s possible that the least-known corner Herald Square building is the Marbridge Building on the NE corner of Broadway and West 34th, which went up in 1909. For the last 15 years or so the ground floor tenant has been lingerie store Victoria’s Secret, but when I worked at Macy’s from 2000-2004 I could often be found there — when it was a branch of the British music retailer HMV, which had originated in 1921 and had branched out to NYC from its flagship on Oxford Street in London. The rise of MP3s and streaming put a severe dent in CD, cassette and LP retailing in the 2000s and 2010s. HMV went into receivership in 2018.

The 34th Street subway station is among the most complex in the city and links three separate transit lines. The first to be built was the northern terminal of the PATH train, which arrived at 33rd Street in 1908 (it no longer has an actual exit on 33rd Street, however). Second was the BMT, in 1916, and third was the IND, a relative Johnny come lately in December 1940. When these lines were constructed they had to be built above each other with the IND the deepest, at 40 feet below street level. Meanwhile, Long Island Rail Road tunnels are deeper than all three, running beneath West 32nd and 33rd Streets.

What interested me in photographing the signage in this station are the many original mosaic tablet signs that are still here from the IND, or Independent Subway, construction in 1940. The IND was a transit system that originated in the mid-1920s to compete with the various elevated trains as well as subways run by Interborough Rapid Transit (the IRT, today’s numbered lines) and the BMT (many of the lettered lines; Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit was a reorganization of Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT) which foundered after the 1918 Malbone Street Wreck, in which, during a transit workers’ strike, an inexperienced train operator crashed a train full of passengers into a Brooklyn subway wall, killing many of them.

All competing subway lines were combined under city management in 1940, and have been run, along with bus lines, by agencies such as the NYC Transit Authority and Metropolitan Transit Authority with varying degrees of success since then. In 2012, the MTA faces a massive money crunch due to the drastic drop in fares due to the Covid virus, and the fate of NYC transit service is in play.

I’m a big fan of subway mosaics and I have come to like the IND mosaics more and more over the years, as they are simple white mosaic lettering on a color background for the most part; they dispense with the ornate Beaux Arts signage of the original IRT built 1904-1908 and the “Arts and Crafts” multicolored mosaics of later IRT and BMT stations built from 1914-1928.

The 6th Avenue el clattered up the mid-Manhattan avenue from the 1880s to 1938 between West 3rd and West 57th Street. Though service ended in 1938 and the structure was razed, as seen here, by 1939, service on its replacement, IND 6th Avenue Line, did not begin until December 1940. Here we see it running through Herald Square, with Macy’s on the left.

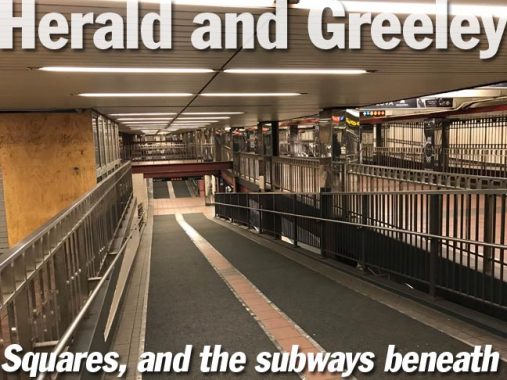

The concourse at 34th Street isn’t usually this depopulated on a Monday afternoon, but that’s the virus for you, and it’s hoped that things get back to normal sometime in 2021. (Though I have to say, it’s easier to take pictures without a whole lot of people around.)

This tiled sign appears at the 35th Street exit at Broadway. The 6th Avenue Line connects to the Grand Concourse in the Bronx (D train); and the F, which runs into Brooklyn via the Culver and on the Queens Boulevard line. Middays, the B train runs via the Brighton line in Brooklyn to Coney Island and rush hours, into the Bronx via the Concourse. Since 2010, M trains have run in Manhattan and Queens only.

Unlike other cities such as Boston, Washington and Chicago, where subway and el lines are defined by color, NYC identifies routes by letter and number. Letters were first introduced in the 1930s with the Independent lines, with the IRT and BMT having separate number systems. The BMT kept its numbers even after subway “unification” in 1940; it didn’t switch to letters until the 1960s. The IRT has remarkably had a stable nomenclature over the decades, losing only two numbers: 8 (the Third Avenue El shuttle that ran until 1973) and the 9 (a skip stop with the 1; it was dropped when the 1 returned to stopping at each station).

There are too many changes to the lettered lines over the years to list here, but one change since 1978 is worth noting: while lines aren’t known as the “orange line” or the “yellow line,” bullet colors, shown here, are determined by what avenue they run under for the bulk of their routes in Manhattan: in the case shown above, the B/D/F/M run beneath 6th Avenue, with N/Q/R/W under Broadway. It’s simple, when you think about it.

This tiled sign presents the motherlode of outdated references. I’ve already mentioned the BMT. The H&M was the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad is what is now called the PATH train and runs from a 33rd Street station to points in Hoboken, Jersey City and Newark.

An ambitious lawyer from Georgia via Tennessee, William Gibbs McAdoo, obtained backing and employed upgraded tunneling methods in 1901, proceeding to do what by then was considered impossible: he engineered multiple tunnels and inaugurated rail service, the first trans-Hudson rail of its kind, between NYC and Hoboken, from 1908-1910 and Jersey City and Newark Park Place in 1911. Newark Penn Station service was added to what was called the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad in 1937. Original service ran between Hoboken and 19th Street (now closed to the general public) and opened February 25, 1908. The H&M was, in effect, the original 6th Avenue Subway — Independent Subway 6th Avenue service did not open until December 15, 1940.

The H&M was, in part, responsible for the old World Trade Center. The railroad had fallen into bankruptcy in the 1950s, but The Port Authority agreed to purchase and maintain the Hudson Tubes in return for the rights to build the World Trade Center on the land occupied by H&M’s Hudson Terminal (the “original” Twin Towers on Church Street), which was the Lower Manhattan terminus of the Tubes.

(As luck would have it, though, the H&M retail apparel chain now occupies the ground floor of the Herald Center, so once again, this sign is perfectly effective!)

FNY explores the PATH’s Manhattan stations on this page. In Manhattan, it’s a redundant version of the 6th Avenue subway without free transfers, but it’s advisable to use it if you need to go to the West Village, as it has stations at 9th Street and 6th Avenue and Christopher and Hudson Streets.

Few remember the Long Island Rail Road’s association with the Pennsylvania Railroad, which ended in 1960, but the Manhattan terminal has nonetheless retained its Pennsylvania name, which it has had since opening in 1910.

To connect the Broadway Line and 6th Avenue Line platforms, there’s a series of pedestrian ramps and staircases, though there are escalator and elevator options. However if you don’t use the ramp you’ll miss these classic IND tablet signs:

One one occasion, the tablet reading: “Uptown, the Bronx & Queens” is right alongside a redundant black and white sign. This situation had been repeated on the other side of the ramp until recently.

The MTA is adamant about removing nonstandard signage, even if it provides correct information. A rule of thumb is: “if a sign wasn’t produced in the MTA sign shop, it doesn’t exist.” Therefore, modern signs can sometimes be seen directly alongside original mosaic signs it would apparently be too much trouble to rip out, as they were tiled directly into the wall.

Just the basics, please, in this corridor connecting the 34th Street station complex and the 33rd Street PATH station. The PATH has its own set of signage rendered in the Frutiger font. However, I avoided taking photos in the 33rd Street station…

…because a second rule of thumb is, “assume all uniformed personnel want to stop photography.” The NYPD has been advised that photography in the subways is permissible, but some still bigfoot photographers nonetheless, and I have read various accounts over the years that PATH personnel absolutely despise photographers, assuming they are casing for terrorist attacks. Avoid PATH photography, I do.

Meanwhile, the former BMT Broadway Line has mosaic sign remnants in the 34th Street station at staircases descending to uptown and downtown platforms. Of course, the MTA has also installed standard black and white signs. The side walls of the platforms also have mosaic “34” signs.

Greeley Square is the wedge of territory between Broadway and 6th Avenue north of West 32nd Street. It was named for the famed 19th Century newspaper editor, Horace Greeley, who according to popular legend advised young people seeking their fortunes to “go west, young man.”

The reality is more complicated.

Horace Greeley, the son of a New England farmer and day laborer, was born in Amherst, New Hampshire in February 1811. The economic struggles of his family meant that Greeley received only irregular schooling, which ended when he was fourteen. He then apprenticed to a newspaper editor in Vermont, and found employment as a printer in New York and Pennsylvania. Seeking to improve his prospects, he gathered his possessions and a small amount of money, and in 1831, set out for New York City. The twenty-year-old Greeley found various jobs, which provided some capital, and in 1834, he founded a weekly literary and news journal, the New Yorker (not the modern-day weekly).

Greeley founded the NY Tribune (the paper later absorbed the Herald; see above) in 1842 and edited it until his death in 1872. He was an ardent abolitionist and an advocate for women’s rights (though he did not advocate women getting the vote), and workers’ rights. In so many words he told those afflicted by the Panic of 1837 to “go west, young man, and grow with the country.”

Assisted by a talented and versatile staff, a number of whom were identified with the Transcendentalist movement, Greeley made the Tribune an enormous success. It merged with the Log Cabin and New Yorker, expanded its staff and circulation throughout the 1840s and 1850s, and by the eve of the Civil War had a total circulation of more than a quarter of a million. This number, however, vastly understated the paper’s influence, as each copy often had more than one reader. The weekly Tribune was the preeminent journal in the rural North.

Greeley served in Congress for 3 months in 1848-1849, but ran unsuccessfully on numerous occasions for the House and the Senate.

His final campaign was for the Presidency in 1872. He was ridiculed for advocating leniency for the south, equal rights for whites and blacks and thrift in government. He was caricatured by Thomas Nast, who was also waging war against Boss Tweed at the time. Greeley lost to Ulysses S. Grant by a wide margin. He lost control of the Tribune to a rival, Whitelaw Reid.

He soon fell deathly ill. When Reid went to see Greeley, he exclaimed. “You son of a bitch, you stole my newspaper!” Years later Reid was asked what Greeley’s final words were. He said “I know that my Redeemer liveth.”

Horace Greeley’s bronze memorial in the square finds him seated with a copy of the Tribune in his right hand. This, by sculptor Alexander Doyle, is the second of two Greeley statues installed in New York City in a four-year span, 1890-1894. This statue was commissioned by the Typographical Society of America: Greeley was first president of Typographical Union No. 6. A second Greeley memorial bronze can be found in City Hall Park.

And, a bust of Greeley can be found at his gravesite in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, where you will also find Bennett Jr. and Tweed.

The former Gimbels Department Store at 6th Avenue and West 32nd was built from 1908-1912 by architect Daniel Burnham. It was reborn as the glassed-in, hollowed-out Manhattan Mall in 1989. When I worked in the area from 1988-1991 I would often get lunch on the 7th floor Food Court, which had large windows facing Greeley Square and the Hotels McAlpin and Martinique. In the late 1990s, though, the building’s owners decided that executives deserved these views more than the rabbling public; lunching shoppers were banished to the basement, while the 7th floor was converted to offices.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

10/25/20