THERE are a few remaining streets in Greenwich Village I haven’t walked, or at least purposefully walked from beginning to end. The Village is known for its Washingtons: Washington Street, Washington Square, even Washington Mews. The father of his country is indeed covered in the Village. Washington Place runs east to west, from Broadway (where its numbering begins) to Sheridan Square at Grove and 7th Avenue South, slotting in between West 4th Street and Waverly Place (which become Washington Square South and North when encountering the Square). It is divided in two by the Square, which is likely how it got its name; the Square was likely named first.

However, some changes have occurred since it was first laid out. On this Thomas Cowperthwait map from 1850, the section east of Washington Square is called Washington Place but west of the square, it’s an eastern extension of Barrow Street. Maps from later on show two halves of Washington Place. In The Street Book (Hagstrom, 1978), Henry Moscow declares it was named in 1833.

Or is the section west of the Square really Washington Place? Some maps, including Google and Open Street Map over the years have labeled the western “section” as West Washington Place, but what I go by is what the Department of Transportation has on its street signs, and they don’t have a “West” on the signs. Surprisingly, I can’t find this conundrum discussed in any of the guidebooks or NY Times online.

Recently I walked Washington Place from west to east, officially from the end to the beginning. The first building of note I encountered is on the west end at Grove Street, and it doesn’t have a Washington Place address at all; rather, it’s called The Shenandoah, #10 Sheridan Square, which went up in 1928, designed by Emery Roth. 1928 was amid the Deco period, the last great period of building ornamentation. The Depression and WWII ushered in a soberness that has yet to dissipate; because today, much office and residential high rise buildings are unadorned glass boxes.

The building still has its original Romanesque design, contrasting brickwork, casement windows and not least eclectic stonework ornaments like the scene shown here. You’ll see more on this page of Tiles In New York. Since I am usually tossed out on one ear or the other when I enter a private area with a camera, I was happy to get some images of the interior lobby at the site and it didn’t disappoint, with multicolored tiling and mosaics reminiscent of the early subway stations built from 1904-1928 (that year again).

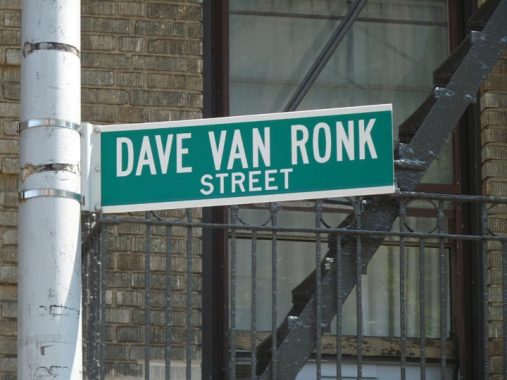

While honorific street signs are usually installed on corners, here’s one in midblock, or at least where Sheridan Square becomes Washington Place across from Barrow Street. Folk singer Dave Van Ronk (1936-2002) is one of those guys I’ve heard a lot about, but have never heard (he was a bit ahead of my time) but his bio did inspire a movie I saw a few years and liked, “Inside Llewyn Davis.” More on Von Ronk.

Because of the sun angle, it was tough to get a picture of this formidable brick building at Washington Place and Barrow Street, officially called #1 Sheridan Square. It was constructed in 1903 as a warehouse for the Consolidated Dental Manufacturing Company and was converted to apartments several decades ago. It has been home as you would expect to several Village artistic characters, such as painter Saul Schary and Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company. The building also housed Café Society from 1938-1950, one of the first desegregated jazz clubs in NYC.

The wedge-shaped building on the Barrow Street side, #2 Sheridan Square, was constructed in 1834 with an 1897 addition, a 4th story.

Here’s the formidable entrance canopy at #15 Sheridan Square, a.k.a. 135 Washington Place, a.k.a. Sheridan Arms. The brick apartment building went up in 1924 to a design by John Woolley.

Today’s photos are a bit fuzzier that usual. The air was quite hot and humid and the heat was actually rising in spots.

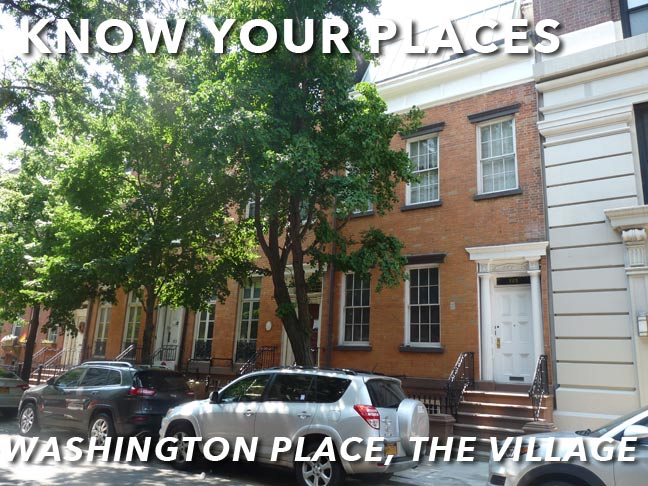

Washington Place is lined on occasion with wonderfully maintained Federal/Greek Revival style townhouses. The trio of #124-128 were constructed in 1834. In some cases their original doorway designs, with Doric columns, have been maintained.

For quite a while I have been puzzled by the medallions or plaques appearing outside the doors of two of these buildings. One, Eagle Hose #2, is likely a volunteer fire brigade. The other, a fire hose and a hydrant with the letters FA, is clearly the emblem of some organization, but I’m stumped. Comments are open at the end of the article!

I may have a partial answer from the Firemen’s Hall Museum:

American fire marks, also known as “badges” and “house plates,” are signs issued by insurance companies that were affixed to the front of a property to mark that the property was insured for fire. Fire marks carried the symbol or the name of the insurer and were made of cast iron, sheet brass, lead, tinned sheet iron, copper or zinc. They came in various sizes and shapes, sometimes attached to a wooden plaque.

Used primarily for advertising purposes, fire marks were used from 1752 to circa 1900. Going back to their early practices, the Philadelphia Contributionship and The Baltimore Equitable Society still issue fire marks.

St. Joseph’s Washington Place School, #111 Washington Place, is the parochial school of St. Joseph’s Parish (see below), St. Joseph’s Academy. The 5-story brick building with a limestone exterior on the first floor and at the windows was built from 1896-1897. An interesting touch is the pair of caducei, with a pair of snakes entwined on a torch. The torch would symbolize learning and enlightenment, while the two snakes were part of Roman messenger god Hermes’ staff. Thus, “we spread learning.”

It doesn’t get a lot of ink in the guidebooks, but St. Joseph’s Church, at Sixth Avenue and Washington Place, designed by architect John Doran in 1833 (the date is prominent on the facing) is the 3rd oldest Catholic Church building in NYC (the Church of the Transfiguration, built on Mott Street, in 1801, and Old St. Patrick’s, built on Mulberry and Prince Streets in 1809, are in older buildings, and St. Mary’s on Grand Street, also lays a claim). It is a mix of Federal and Greek Revival styles. The facing is actually a later addition and the actual 1833 exterior walls can only be seen from Washington Place.

St. Joseph’s is among the oldest parishes in Manhattan; only St. Peter’s on Barclay and Church Streets (est. 1786), St. Patrick’s (1809), St. James (Oliver Street, 1829) and Transfiguration (1827; the parish purchased its 1801 building from the Zion Protestant Episcopal Church in 1853) existed before St. Joseph’s.

Though the location and walls are still those erected in 1833, the church has suffered several devastating fires over the years that have necessitated both the rebuilding of the 6th Avenue front as well as the interior and most of the stained glass windows. The last such restoration took place in 1992.

Sgt. Charles H. Cochrane (1943-2008), honored on the sign, was the first NYPD officer to publicly announce himself as gay and later founded the Gay Officers Action League (GOAL).

I’ve recounted the story of 6th Avenue’s “country medallions” quite a bit in FNY, so here’s a link to my original article about them. I will say that the loss of most of them is a shameful, careless episode in recent Department of Transportation actions, but few current NYers remember when most of 6th Avenue had them as recent as the early 1990s. This is the only Canada plaque remaining, at 6th Avenue and Washington Place.

Formerly Crow’s Bar, #85 Washington Place off 6th, sits in place of a former tavern called The Stoned Crow, which had been there from 1993-2010.

The Stoned Crow is owned by Betty Gordon. And judging by the decor, Betty likes these things: movies of any kind, particularly Hitchcock, the posters and stills of which cover nearly every inch of wall and ceiling; caricatures of rock stars and other famous people; images of crows; and hand-drawn cartoons, particularly the ones in the back room that depict Betty as a kind of Heavy Metal Comics superhero, all hair, thighs and cleavage. Those sketches depict “Super Betty” inflicting pain on those that would disobey her multiple Commandments of Pool Playing. No drinks near the table. No smoking at the table. Don’t leave cues lying on the felt. Careful with the balls. [Eater]

A pair of Greek Revival townhouses at #73 and 75 Washington Place constructed for a chemist and a physician, respectively.

Though Washington Place does not extend through Washington Square it’s possible to walk on a straight line (around the fountain) to the eastern piece of Washington Place via a lengthwise park corridor. On this July 2021 Saturday, there was no sign of the recent strife regarding park curfews, though I was here around high noon. Musicians were out in force and I slipped the better of the two piano players I encountered a couple of bucks.

The history of this particular spot in NYC is long and varied; it was first a marshy area surrounding Minetta Brook, which ran from Midtown southwest to the Hudson River), then a cemetery (1797; a tombstone dated 1799 was actually found during the excavation process during renovations from 2002-2011) a parade ground for military marching drills (1826); and finally, a public park (1827).

Looking north past the fountain (which was installed in 1872, replacing an earlier one from 1852), to Stanford White’s memorial George Washington Arch (1892) and One Fifth Avenue, a hotel built in 1926, with a restaurant called One Fifth on the ground floor I would frequent in the 1980s.

If traffic czar Robert Moses had got his wish, the circle around the fountain, which was once used to turn 5th Avenue buses and was open to motor traffic when the Queen of Avenues was one-way, and the fountain would be moved to make way for a connector road between 5th Avenue and LaGuardia Place. Locals fought Moses tooth and nail (as they did against his proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway on Broome Street) and after a lot of vitriol, the Master Builder backed down. However, the fountain was moved anyway between 2007-2011 during park renovations.

Decades ago, Washington Square took over the names of MacDougal Street, Waverly Place, Wooster Street and West 4th, which became Washington Squares North, West, East and South respectively. This change was made pretty early, soon after the park’s borders were set.

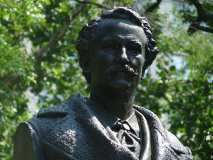

I don’t know if a present-day industrialist would rate a memorial in Washington Square today, but Alexander Lyman Holley is here, and his 1889 bust by John Quincy Adams Ward isn’t going anywhere.

While traveling in Europe, he observed the Bessemer process for making steel and realized its practicality and efficiency. When he returned to the states, he convinced his employer to buy the American patents for it and he became the foremost designer of steel works in the country.

The monument was dedicated Oct. 2, 1890, a gift from three professional engineering societies, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the Institute of Mining, Metallurgical and Petroleum Engineers and the American Society of Civil Engineers, though money was raised from related professional groups around the world.

Not everyone was thrilled by the gesture. Many critics, including the editorial boards of several New York newspapers, complained that Holley was hardly a household name. Dianne Durante, author of “Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan,” records the NY Times’s indignant (and rather tortured) thesis from April 24, 1890: “The time is coming … when sites for statues in the Park will be too scarce to be assigned to effigies from which the general public will derive its first knowledge that the originals of them have existed.” [NYC Statues]

For well over a century the campanile of Judson Memorial Church, at Washington Square South and LaGuardia Place has dominated the view south from Washington Square. The church is another work of architect Stanford White, and features stained glass by John LaFarge and sculpture by Augustus St. Gaudens and went up in 1896; it was designated a NYC landmark in 1966. Adoniram Judson was the first American baptist missionary in Asia, working primarily in Burma. Like a lot of property in the area, most of the complex now belongs to New York University.

After fighting in South American wars of liberation, using what today would be called guerrilla tactics, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882) organized and led insurgencies leading to conquests of Sicily and Naples which ultimately produced the unification of Italy in 1860. Abraham Lincoln offered Garibaldi a command in the Civil War, but Garibaldi asked for the post of commander-in-chief, which Lincoln was unwilling to consent.

Garibaldi resided in a house on Rosebank, Staten Island’s Tompkins Avenue from 1851-53 with his friend, Antonio Meucci, who invented the telephone before Alexander Graham Bell received his own patent for it. The house is now used as a museum.

Three blocks of Washington Place extend east of the Square. Remarkably, the buildings on this stretch do not belong to any Landmarked district, despite their occasional historic significance; they are mostly 7 or 8-story structures built between 1905 and 1935 for light manufacturing, with some apartments mixed in. One, the Asch Building on the NW corner of Greene Street (since renamed the Brown Building) was the location of one of NYC’s most heinous manslaughters, the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911, in which more than 140 immigrant, mostly female, sweatshop employees were killed when they were trapped in a rapidly spreading fire when the exit doors on their floor were locked to prevent shirking or pilferage. The Triangle owners faced no severe legal repercussions, similar to the figures behind the General Slocum steamboat fire 7 years earlier in which over 1000 perished; life has always been considered cheap by one sector or the other.

Wrapping ip Washington Place at Broadway, with a trio of buildings, #714, 716 and 718, constructed from 1890-1906 and part of the NoHo Landmarks designated area.

Nearby #722 Broadway features some spectacular metalwork at its entrance.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

7/25/21

9 comments

Just want to thank you for this website. I spent my first 35 years in NY always admiring the architecture and wondering what the history was. Wish I had this site back then!

The late NYC Mayor Ed Koch lived in a rent-controlled apartment in a building on Washington Place east of Washington Square and west of Broadway. He had occupied it for many years prior to his 1977 election. Believe it was #14 Washington Place. When he was inaugurated January 1, 1978, he traveled by M6 bus from the corner of Broadway and Washington Place to City Hall (source: NY Times, 1/2/1978). According to the same Times article, his rent was $250 per month. I believe he kept the apartment for some years after becoming Mayor and residing in Gracie Mansion.

The former Triangle Shirtwaist Building holds the dubious record for the building that sustained the deadliest fire but still remains standing. Runners-up are the Winecoff Hotel in Atlanta (1946, 119 deaths) and the MGM Grand (1980, 85 deaths). The Ohio State Penitentiary’s main building (1930, 320 deaths) survived the fire but was torn down about 25 years later.

It would have been nice if NYU knew how to reuse some of that historic architecture below Washington Square rather than demolish pretty much all of it, but I guess that was mainly because much of it felt too small for them to use.

Looking at the Dave Van Ronk photo I couldnt help notice the ladder type fire escape in the background

and what a boon it was to the burglary industry.We had the old type that just connected two adjoining

buildings together but didnt go from floor to floor with a ladder.Which made me wonder what would

you do if BOTH buildings side by side were on fire?

There was an old joke at NYU that probably still exists…that the statue of Garibaldi would turn his head if “a woman of virtue” walked by.

More importantly, I have three family connections to the NYU area beyond myself. My Aunt Gus reputedly worked in the Triangle Factory as a little girl, and her life was saved in the fire when she crawled across a ladder to the NYU Chem Lab across the courtyard. Reputedly.

For a certainty, her future husband, Uncle Joe Samberg, was playing with his pals in Washington Square Park when they saw fire engines racing to a blaze. Being kids, they mounted their Schwinn bicycles and pedaled off to the scene, which was not far away, as we know. They had a perfect view, watching fire ladders and towers that were too short to reach the eighth, ninth, and 10th floors try to grapple with the inferno.

Then they saw the horrifying part…people edging onto the ledges and jumping to their deaths. A couple hugged, kissed, and held each other as they went down, slamming into the round glass windows on the sidewalk that illuminated the Asch Building’s basement.

My third connection is my father: he graduated from NYU in 1949. He paid $9 a credit, an awesome sum back then.

When it was my turn to attend from 1980 to 1984, it was $250 a credit, still an awesome sum. I did a paper on the Triangle Fire for “Social History of New York City” and walked around the Asch/Brown Building with a tape measure, determining the actual width of its staircases and capacity of its elevator, which came with an operator (like many NYU buildings at the time). I figured that the building’s staircases could not accommodate the panicky mob on any occasion.

The floors are now connected to other NYU buildings, and are part of the chemistry department — the eighth floor was a lab, the ninth a lecture hall. I couldn’t help but wonder what would happen if the chem lab blew up — in the middle of the annual ceremony to honor the Triangle Fire.

Sad that there isn’t even a plaque on the Asch/Brown Building to commemorate what happened there.

Fire marks were used in early New Orleans when multiple commercial fire companies existed. A fire company, either by contract with the property owner or the insurer, would know it had to put out the fire if the mark corresponded with its company. Absent a fire mark, the different arriving companies competing for the job would argue over who got to fight the fire. The townhouses on Washington Place may have displayed the marks for similar reasons.

I’m here looking for pictures of 88 Washington Place (kittycorner from St. Joseph’s) as it was in 1922 when my grandparents lived there. It was also home to painter John Sloan 1915-1927.

Number 88 is marked on ‘Where all the Village meet to eat’ – An accurate and detailed map of Greenwich Village and Environment. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1927. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/94e0b066-323e-ae4f-e040-e00a18067dd8

The building was demolished for new construction in 1964, according to Greenwich Village Historic District Designation Report. Volume 1. New York: The Commission, 1969. The history, architecture, and facts about every building in the Village, house number by house number. https://www.nypl.org/about/locations/jefferson-market