NOT having a plan is sometimes the same as having a plan. The month of August continually disappoints me. Every year, I call it the month “anything can happen.” It’s my birthday month after all and I remember magical moments from past years. Recently, though, as the climate change they say is happening kicks in, August turns out to be one gray, humid blob and my energy level drops down considerably. Humidity or no, I resolved to get my ‘steps” in; I always carry my camera and today decided to invade Long Island City’s western region. I walked mainly on 37th and 38th Avenues and wound up at Queensboro Plaza to catch the #7 homeward.

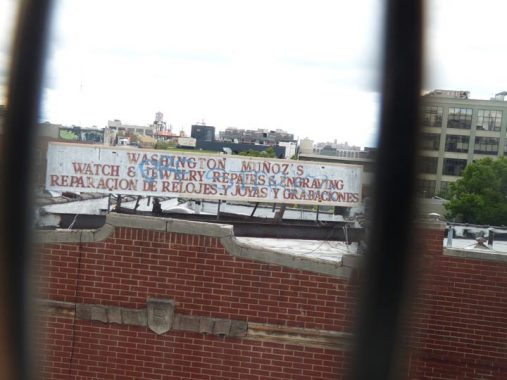

For reasons explained below, it’s more difficult to shoot photos through the fencing on the 36th Avenue station platform. This sign, mounted on a rooftop and advertising a watch and jewelry repair shop below, has been here for donkey’s years, and the repair shop is still down there. I don’t know if Washington Muoz is still in charge, but his name was coincidental: before Queens streets had numbers, 36th Avenue was Washington Avenue and the station still indicated Washington Avenue before station renovations in 2017.

I’m an unabashed fan of the elevated station renovations the MTA did with the Astoria Line stations from 2017-2021: the thick plastic walls that allow street views, at least during the day; the wood paneling on the canopy roofs; the retention of the original 1917 ironwork; the “waiting rooms” on the turnstile levels; and even the station art, in this case the kaleidoscopic design by Maureen McQuillan, titled “Crystal Blue Persuasion.” I go into these new designs in detail on this 2018 FNY page.

I complain about the MTA a lot, but I take its subways and railroads a lot too. I hope these stations serve as the template for future elevated station renovations, if any are planned.

As favorite old street signs are taken down and replaced, I’ve begun to pay more attention to the designs of store sidewalk signs. For example, the two liquor store signs are from two different eras. The Chinese restaurant sign is in Cooper Black, a very popular font for signs facing sidewalks. Note the different languages, Chinese, Spanish, Arabic and a language from India I am unsure of (help me in Comments). In fact the pharmacy signs are in that language and also the Spanish “farmacia” indicates there are Spanish speaking customers. These are all on 36th avenue west of the station.

Moving on to 37th Avenue, here are views of “Big Allis” from 24th Street as well as 38th Avenue and 12th Street.

The Ravenswood Generating Station (found at the intersection of Vernon Boulevard and 36th Avenue in the Ravenswood section along the East River) has the capacity to provide 21 percent of the electricity consumed by all of New York City. Its colloquial name is “Big Allis,” a sobriquet earned due to the name of its builder — the Allis-Chalmers Corporation — and the fact that when it opened in 1965 it was the first million kilowatt power plant upon the Earth.

It was originally built for Con Ed, but deregulation forced them to sell the plant in 1999 to Keyspan, which later merged with National Grid, who sold it to Trans Canada in 2008. Both steam and electrical generators are powered largely by natural gas, but they use small amounts of fuel oil and kerosene as well. Its iconic red and white stacks are nearly always visible from Astoria and Sunnyside as well as Roosevelt Island and Midtown Manhattan. The plant sits on the former site of the Jacob Blackwell Mansion, built in 1744.

–Mitch Waxman of the Newtown Pentacle, in a now-deleted article in Brownstoner

The collection of auto repair and tire shops concentrated in the Iron Triangle east of Citifield in Corona have been largely evicted and their shops bulldozed. But there are Iron Triangles, Squares and Rectangles all over town. I found a concentration of them on 37th and 38th Avenues between 21st and Crescent Streets.

I have noticed that auto repair shop signs have their own esthetic. Bold lettering in all caps. Red and yellow predominate (as they do on bodega signs). There are interesting touches, like the painters’ palette on the Twins Collision sign, indicating they also do auto paint jobs.

Looking at the LIC map, the Long Island City street grid runs slightly askew against one of the main north-south drags, 21st Street (Van Alst Avenue). Some numbered streets were skipped because of this and 21st Street is followed by 14th Street when heading west. There’s a lengthy triangle formed by 14th when it runs into 21st at 37th Street, named quite prosaically 16 Oaks Grove, for the sixteen oak trees ringing it. This is the largest vegetation concentration in this largely commercial-industrial region.

Hotel Nirvana at 37th Avenue and 12th Street…a standard too high to match? One of the many high rise residential buildings under construction or recently opened in this part of town.

Engine 260 was founded in Long Island City as part of the LIC Fire Department in 1895 and joined the FDNY upon Queens’ consolidation with Greater New York in 1898. The firehouse, though, is a design popular in 1930, give or take a few years before and after. Note the red glass on the exterior lamps.

A pair of people storage towers, at 37th and 10th and 38th and 9th, one finished, the other unfinished. This is the prevailing style for high rise buildings in the 2020s. One is a La Quinta hotel.

Queens works! On 38th Avenue between 9th and 21st Streets, with D & L Ornamental Ironworks, New Bangla Motor, Twinco Supply Corp., Regal Page Publishing and King of Queens Auto Services.

Would like to tell you more about the Long Island City Queens Public Library at 21st Street and 38th Avenue, but the QPL says nothing about its date of construction or design on its website. The entrance is flanked by two massive tablets with arcs of type spelling out poetry in various languages. (The art is by Toshio Sasaki)

Some of the incongruities of local zoning are displayed here, as we have this 12-story structure slotted in between a gas station and one-story auto body shops on 21st Street at 38th Avenue. It is formerly a Comfort Inn, but I don’t know its present franchise. No doubt, weary motorists in LIC spend overnights here and the upper floors must have a fantastic view. But how did it ever get built here?

Demonstrating further the incongruity of high-rise residences and hotels in this neck of LIC, here’s Toro Tires, some ore auto repair joints, and the Queensbridge Con Ed substation on 38th Street between 21st and 23rd Streets.

It’s not mentioned often but Astoria and its neighbor Ravenswood were once a hotbed for silk manufacture and production. Several remaining buildings scattered over the region are former silk production buildings, with minuscule clues to prove their past identities.

The Silks Building, 38th Avenue and 24th Street, was constructed in the 1920s for the Franco Scalamandre Silks Company. The company produced luxury silk and textiles used in wall coverings, upholstery and other furnishings. Scalamandre was employed by multiple presidential administrations to furnish the White House, and the Hearst family’s mansions have also used the firm. A painted sign on 24th Street still identifies it as the Scalamandre silk works, but it’s hidden by foliage in spring and summer.

Scalamandre moved to South Carolina in 2004, and the building, still called the Silks Building, is being subdivided into residences.

For more on silk production in LIC, see this FNY page.

This pair of buildings at 38th Avenue and 28th Street still have some of the architectural elements they had when they were built in the early 20th Century especially at the entrance and roofline. Here’s what they looked like in 1940.

Some interesting art depicting fish women, or mer-people, outside Beija Flor at 38th avenue and 29th Street. “Beija flor” means “flower kiss.”

Why depict this rather barren alleyway issuing from 38th Avenue between 29th and 30th Streets? It’s an actual road possibly dating back to the colonial era called Old Ridge Road and as you can see, there are a couple of properties that face it. It likely survives because it’s a former trolley right of way. See this FNY page for more.

A close look at the brick exterior facade of 31-18 38th Avenue reveals the words “L.J. Concrete Corp.” spelled out in…bricks! The firm seems long gone from this location.

I have an affinity for red and white color combinations, thus 32-02 38th Avenue isn’t as bad as it could be, perhaps. The building replaced a frame house and barbed wired parking lot in 2019.

Meanwhile, across the street, here are 32-01 and 32-03 38th Avenue, which are considerably older. Again, here are what they looked like in 1940.

33-01 38th Avenue looks thoroughly modern but it’s actually a residential building called The Addition — it was constructed in 2016-2017 on a two-story brick building from the early to mid-20th Century.

Pierce-Arrow’s 1913 Long Island City factory still stands on 38th Avenue between 34th Street and Northern Boulevard across from, appropriately, a gas station. Longtime readers of FNY know of my admiration for stolid brick architecture, and the factory imparts a sense of permanence, even though its parent company existed for only thirty years. The building once had a lengthy, arrow-shaped neon sign, emblazoned with the word “Pierce.” Much more on the Pierce-Arrow factory on this FNY page.

In the early 20th Century developers and architects had a unique opportunity with Northern Boulevard, which runs just north of the Sunnyside railroad yards between Queens Boulevard and 48th Street. Massive properties could be built here, home to manufacturing, warehousing and offices. Many remain intact, like this building of many addresses, one of which is 32-20 Northern. (Another one further east is Standard Motor Parts, where I spent a few weeks in the graphic department in 1999.)

A look at Honeywell Street, which bridges Sunnyside Yards between Skillman avenue and 35th Street and Northern Boulevard and 33rd Street. All of 35th Street in Sunnyside was formerly called Honeywell Street, but this section survives.

Until 2000 or so, most bridges spanning the Yards were fearfully decrepit, and so bad that at least one or two was closed. The bridges kept their old incandescent lighting and other relics. They were torn down and replaced with rather boring new ones at that point.

A massive overhead collection of metal can be seen at elevated lines meeting at Queensboro Plaza, the Astoria Line seen here and the Flushing Line. Until 1942 they were joined by a spur of Manhattan’s 2nd Avenue El that went over the Queensboro Bridge.

See the “Bear” sign at this auto repair shop at Northern Boulevard near 31st Street? The symbol, or logo, is very old and was first used by the Bear Manufacturing Co., established in 1917, in the early 1920s. Though Bear went out of business in 2009, there are still a number of signs around, possibly from inertia as proprietors leave them in place. Bear is not to be confused with the more recent Great Bear, which is still in business.

Post-top lampposts like this were at one time found in the hundreds or thousands beneath elevated trains but have been mostly supplanted. There are a couple still in place, like this one on Northern Boulevard.

The Queensboro has been known as the 59th Street Bridge by Manhattanites since it was built in 1909, but another name was added, that of popular NYC mayor Ed Koch (1924-2013) two years before his death. Interestingly it was not named the “Edward I. Koch” Bridge, but just plain Ed Koch. I noted two Department of Transportation signs, one with Queensboro on it, the other not. Consistency isn’t a virtue at the DOT.

Dutch Kills Green Park was built about 10 years ago on the north side of Queens Plaza at the Bank of Manhattan Tower, once the tallest building in Queens when constrcuted in the Roaring Twenties, but now just a mid-sized building compared with the massive glass towers that sprung up beside it in the 21st Century’s Roaring Teens and Twenties.

In 1650, Dutchman Burger Jorissen constructed a grist mill that today would be on Northern Boulevard between 40th Road and 41st Avenue. The mill existed on the site for about 111 years, until 1861 when it was razed by the Long Island Rail Road. The Payntar family by that time owned the mill property (40th Avenue was called Payntar Avenue until the 1920s) and had placed millstones that had been shipped in by Jorissen around 1657 in front of their house. The mill was demolished in 1860 except for its sluice, a sliding gate or other device for controlling the flow of water, which survived for several decades. When Sunnyside Yards, Queens Plaza and the elevated were constructed, the millstones were fortunately preserved and embedded in the traffic plaza; after being removed for a time from 2009-2011 while Dutch Kills Green was constructed, they were replaced here, unfortunately open to the elements.

With its new glass guardians, Queens Plaza looks very little like it did when I surveyed it for FNY in 2007.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

8/22/21