By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

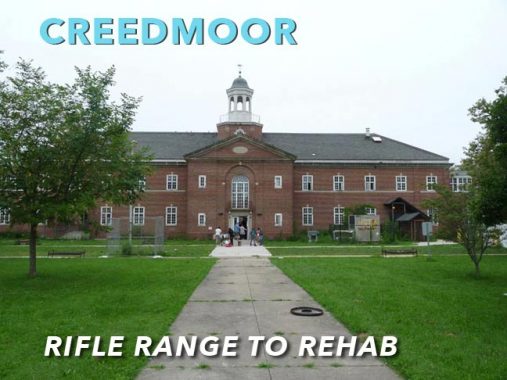

To the south of Alley Pond Park is another sizable parcel of land that is lightly developed amid the tract housing and garden apartment monotony of eastern Queens. The Creedmoor Psychiatric Center is a former farm and shooting range that became the largest mental health facility in the city, with a population of 7,000 patients at its height. With deinstitutionalization, rise of prescription drugs, and changes in public policy, the campus is mostly silent and balkanized among various organizations, with its edges given up to schools, parks, and residential developments.

The most recognizable feature of Creedmoor is Building 40, visible from great distances. Completed in 1959, it has room for 1,068 patients and is the second tallest structure in eastern Queens after the North Shore Towers. Its design is nearly identical to the Manhattan Psychiatric Center at Wards Island, also a tower of yellowish brick that dominates the skyline. This view is from the eastbound Grand Central Parkway which runs atop the glacial terminal moraine, where the forested hills give way to the gently sloping coastal plain.

I entered this campus on Winchester Boulevard near Building 60, the Stepping Stones Transitional Residence that is used by young adults with mental health conditions. To my surprise there was no security guard at the gate, so I continued to carefully walk the grounds without attracting attention. Next to this building is the Lifeline Center for Child Development, a school for children with diagnosed behavioral and emotional concerns.

Similar to a traditional college campus, behind Building 60 is a quad-like park with straight paths intersecting at a circle. Perhaps it had a fountain or monument long ago, but nothing decorative here at this time.

Building 18 is on the opposite side of the quad from Building 60. It is vacant and its appearance suggests that it was an assembly hall. Its designer, William E. Haugaard was the State Architect responsible for many public buildings during his service between 1928 and 1944, such as prisons, hospitals, armories, and office buildings.

Building 68 is the Faith Chapel that was used for religious services by the patients and staff. Its appearance has the stylistic elements of the chapel at Fort Totten and the library at Brooklyn College. The chapel has an organ and American Guild of Organists has a highly detailed page on this building.

The second tallest structure on campus is the power plant, which used coal when it was constructed. For this reason, a freight spur of the Long Island Railroad ran from Floral Park to the power plant. This Romanesque-inspired facility was designed by Lewis Pilcher, who preceded Haugaard as the State Architect. After Creedmoor switched its heating source from coal to oil, the freight spur was recaptured by nature. The detailed ARRT’s Archives has photos from 1952 of a rare railfan trip showing a steam engine pushing through the weeds on the Creedmoor spur.

The loading dock of Building 77 looks like a station platform but the rail spur ran behind this building. The side facing the street was used by trucks. One should note that like other self-contained government complexes across the city, Creedmoor has its own street grid. Unlike the forts and public colleges, the road names here are purely functional: Avenue A through G, and street numbers from one through six.

No honorees or plaques anywhere at Creedmoor, but I can mention a few famous patients who slept at this campus: rock musician Lou Reed, jazz pianist Bud Powell, composer Paul Abraham, and folksinger Woody Guthrie who died here in 1967.

At this point, readers are probably asking when I will get around to sharing the interiors of the abandoned buildings at Creedmoor. Sorry, nearby there was a police car and I did not want to risk arrest for trespassing. Besides, there are plenty of urban explorer sites whose authors have been inside to document the graffiti, bird droppings, and rusting medical equipment.

While the state decides the future of the abandoned buildings, nature takes its cue to conceal them in vegetation and give the birds a home. Likely, they will be demolished as their architectural and historical elements are not unique enough to merit preservation.

The sight of abandoned buildings brings horror films to mind and the real-life abuses that took place here in the past. In the 1940s, a dysentery outbreak resulted from unsanitary conditions at Creedmoor. In 1974 when the city was at its own low point, Creedmoor had its worst 20 months on record: three rapes, 22 assaults, 52 fires, 130 burglaries, six suicides, a shooting, a riot, and an attempted murder. In 1982, author Susan Sheehan documented a schizophrenic patient’s experiences at Creedmoor in her Pulitzer Prize-winning book Is There No Place for Me? Finally, in 1984, a patient died after being restrained in a straitjacket and beaten by a staff member. Fearing for their safety, staff members sometimes brought in weapons to defend themselves. Built with idealism as a farm colony, Creedmoor nearly matched Willowbrook in its notoriety for abuses during the mid-20th century.

Not everything that is old deserves to be demolished if it can be repurposed. Building 74 next to the chapel was given a new brick exterior and looks as good as new when it reopened in 2012 as temporary housing for discharge-ready patients.

On his stroll through Creedmoor, Kevin Walsh reminded me that there’s an art gallery here, Building 75, a former cafeteria that hosts The Living Museum. Founded in 1983 by art therapist Bolek Greczynski and psychologist Dr. Janos Marton, its collection is produced by the patients of Creedmoor. From its origin at Creedmoor, the concept of “living museums” has since spread to hospitals and asylums across the world.

(One of these days I’ll post photos of the artwork I found inside the museum from my visit in 2006. –ed.)

At this point, I’d like to do a historical survey of Creedmoor that explains its ability to avoid becoming engulfed by the borough-wide street grid. The story takes us back to 1872, when the state teamed up with the National Rifle Association to purchase the 70-acre Creed farm for a long-distance shooting range. In this 1877 illustration from Harper’s Weekly, we are looking north towards the hills of the terminal moraine. On the south side of the range was the Creedmoor station on the Central Branch that was built by Alexander T. Stewart. The line ran from Flushing to Floral Park. Its route is seen today in Kissena Corridor Park and Peck Avenue.

Although Stewart’s celebrated line was abandoned in 1879, the segment between Creedmoor and points east continued to operate for a few more decades, mostly as a freight spur. It was officially closed in 1966 with the tracks removed and its right-of-way told to homeowners who expanded their backyards. The NRA shooting range closed in 1907 as more people moved into the area and complained of noise. Its legacy can be seen on the map: Winchester Boulevard, Range Street, and Musket Street. A type of rifle cartridge, the 6.5mm Creedmoor also takes its name from this place. This isn’t the only former shooting range in eastern Queens. Have you read about Interstate Park, where pigeons were shot for sport?

Following the departure of the NRA, the state used Creedmoor as an asylum with a farm colony, ideal for its rural location. The first patients arrived from Brooklyn, which was becoming too dense and urbanized to accommodate a sizable campus with a farm. For the next four decades, the surrounding landscape was gradually laid out in a grid of streets as farms were sold to residential developers. Only the Adriance farm survived urbanization as it was included within the Creedmoor campus. Its produce and livestock were tended by the patients as the city’s last farm colony. In this undated aerial photo from the NYPL collection, we see the campus amid farmland during the Great Depression. On its eastern side is the rail spur that provided coal to the heating plant.

In this aerial shot from 1951 from the New York State Archives, the campus is enveloped by tract housing, with Cross Island Parkway running atop the plain. Highlighted are Winchester Boulevard, and the parallel state routes Union Turnpike (25C) and Hillside Avenue (25B). The Creedmoor rail stub is in orange, no longer terminating inside Creedmoor. Another Forgotten-NY favorite is shown with the green line, Long Island Motor Parkway. Building 40 had not yet been built, but the portion of the parkway running on its site was already removed. Its trace can be faintly seen in the woods and cornfields.

The land south of Hillside Avenue was the first portion of Creedmoor divested by the state. It was later sold to the Hollis-Bellaire-Queens Village-Bellerose Athletic Association, which has its private fields there, and to the Cross Island YMCA which has its community center on Hillside Avenue. On the east side of Cross Island Parkway the psychiatric center gave up its 47-acre farm to the Queens County Farm Museum. Nearly two decades later, the Frank Padavan campus of public schools opened on the portion of the campus between the farm and the remainder of the Creedmoor property.

In recent years, proposals for Creedmoor included a minor league Mets stadium, the controversial sale of a parcel to an Indian Orthodox Church, and senior housing. On its western edge, some of the abandoned buildings were demolished with 8.5 acres sold to the Country Pointe Circle residences. As its intentionally misspelled name suggests, it’s either an attempt to appear fancy or historic by using Ye Olde English spelling with useless silent letters.

I can’t imagine the entirety of Creedmoor becoming a gated community of private streets and pretty homes. More likely, there will always be a need for land to accommodate the growing school population, utilities such as parking and garages, parks, and services for the most vulnerable members of society.

Visit New York’s other former farm colony on Staten Island, today a forested park that hosts abandoned buildings. Nearby, Kevin visited the dilapidated Seaview Hospital in 2000. Another former campus for the people with disabilities, the Willowbrook State School is today the College of Staten Island. In uptown Manhattan, the former Bloomingdale Asylum is today’s Columbia University.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

8/14/21