As mentioned on a recent post, on a sparkling December Saturday (quite unlike the following one during which I’m writing this) I decided to walk Chambers Street then across the Brooklyn Bridge into Brooklyn Heights. Instead of doing epically long posts I’m in the mood to chop them up into palatable chunks, which saves me some time. I was actually hired for fulltime work with Marquis Who’s Who, which I’ve been doing since October: I have to write about people who have bought sections in the book, which includes some rewriting but a good deal of fresh research, so I do like to parcel some time on the weekend to just veg. Today, I’ll concentrate on what I saw on Chambers Street and one of its tributaries that I hadn’t paid much attention to at least formally.

My impression when first seeing it on the map when I was a kid was that Chambers Street must be named for judge’s chambers, as it runs near Foley Square, which has NYC’s largest concentration of criminal courts in the city (downtown Brooklyn is a close second). However, it’s named for an 18th Century Supreme Court justice, John Chambers. The street runs with two-way traffic from the Municipal Building west to Battery Park City, receiving a western extension when the latter opened in the 1980s. The IND 8th Avenue subway (A,C,E) IRT 7th Avenue subway (#1, 2, 3) and Nassau Street BMT (J, Z) all stop here. Despite being beneath the Municipal Building, the BMT Chambers station has long been the city’s most decrepit.

On sunny days in winter, dark shadows can play havoc with photography; it may be better to head out on cloudy days. In any case, Hudson Street begins at West Broadway and Chambers, heading north until it reaches West 14th at 9th avenue. The building here with the slanted, or chamfered, corner is #1 Hudson and I know very little about it, as it isn’t documented online because it is situated out of the many Landmarked Districts in the surrounding area. I do know the former office building is now strictly residential.

I do know about this 7-story building, the Cosmopolitan Hotel, on the NE corner of Chambers and West Broadway. Recently redubbed as a luxury hotel called The Frederick, the Cosmopolitan Hotel’s pedigree goes all the way back to 1845.

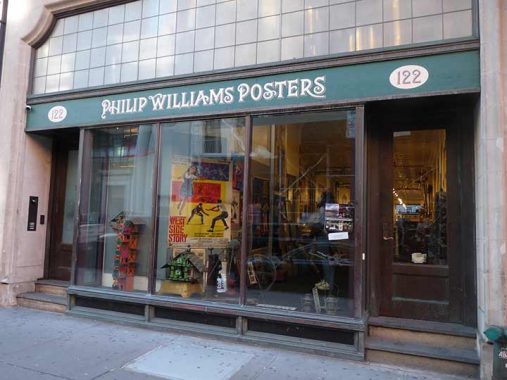

That year, a tobacco merchant named James Boorman built a boarding house at the corner. At the time, Chambers Street was a tree-lined route on which personnel working for City Hall and neighboring endeavors lived. The building then at #122 Chambers was said to have been the first house in NYC with a bathtub. As commercial businesses started to fill in the area, Boorman built his new boarding house so travelers doing business at these places had a way to spend the night. What became the Cosmopolitan was originally 4 floors with New Orleans-style ironwork at the second floor. It wasn’t originally called the Cosmopolitan but initially was known as the Frederick and then the Girard House.

In the 1860s it gained two floors and changed its name to the Cosmopolitan (the seventh floor was added in 1989). It remained a respectable place for decades but by the 1960s, it was single-room occupancy called the Bond, just above homeless-shelter status. Its fortunes went on the upswing again as Tribeca became a hip neighborhood, and recently, new ownership has renovated it into a luxury place called the Frederick once again. It’s shown above with 56 Leonard, the “Jenga Building,” looming over it on the left.

The late great Christopher Grey discussed the building in the NY Times in 2009, and added some vintage postcard views.

124 Chambers, formerly Ecco Italian, retains its 1930s restaurant sign, when it was the Lorenzo Cafe. You can make it out in this archival photo from 1940.

Likewise, #122 Chambers has kept the same glass blocks above the front entrance that it had in 1940.

District Council 37 is New York City’s largest public sector employee union, representing over 150,000 members and 50,000 retirees. The Ionic-columned DC 37 Health Center, #115 Chambers, is the former Irving Savings Bank, constructed in 1926.

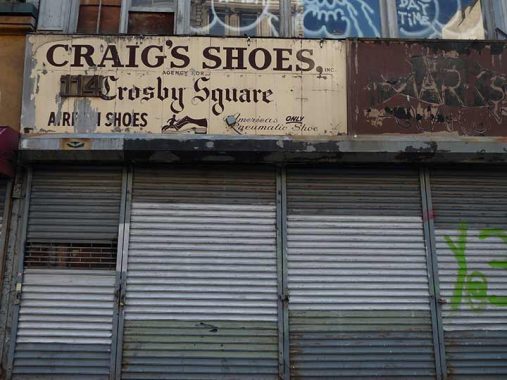

At #114 Chambers is this sidewalk sign of indeterminate vintage. According to Ephemeral New York, there has been a “shoe district” in Tribeca centered on Chambers and Duane Streets that has mostly disappeared these days. “Crosby Square” is a longtime shoe brand, in business since 1867. If anyone can identify the word at lower left, Comments are open. Craig’s Shoes was in business between 1949 and 2006.

The Patriot, at #110, makes a point of advertising its women bartenders. I have been in but once, following a Manhattan-Brooklyn Bridge tour, with a couple of out of town cousins. The bartender was indeed friendly and we had the usual buyback after four drafts. However, I was unfazed after five, which may reflect some H2O added to the brews.

The Cary Building, on the corner of Church and Chambers, is a cast-iron front structure completed in 1857 in the Italianate style, and originally housed a dry goods store, Cary, Howard and Sanger; IsaacCary had founded the store in 1827, which changed hands a number of times and survived until 1896. It was converted to luxury residences a number of years ago. The cast iron frontage was executed by Architectural Iron Works. The Church Street side is much plainer because until the 1920s, it never faced Church, which was widened during the decade. The building extends through to Reade Street a block north, where there is identical frontage.

The Jenga Building horns in again, as it tends to do.

The Italianate cast iron fronted building at #77 Chambers was built in 1848 also with the aid of the Architectural Iron Works. Next door at #75 is the last remaining piece of the former Irving House Hotel.

The easternmost block of Chambers Street between Broadway and Centre Street is awash in Beaux Arts architectural splendors. As Pop Gold Radio DJ Don Tandler (“The Record Handler”) says, “They don’t make ’em like this anymore and they don’t even try.” On the left is the Emigrant Savings Bank building, constructed in 1912. The bank itself was organized in 1850 by the Irish Emigrant Society and NYC Archbishop “Dagger” John Hughes to protect savings of newly arrived immigrants, who in that era were mostly Irish. From what I understand, the interiors are replete with embellishments such as stained glass skylights, teller cages and allegorical figures representing mining, manufacturing and agriculture.

In the center is of course the NYC Municipal Building designed by McKim, Mead and White and completed in 1914. When it was built through traffic on Chambers Street went right through the central arch; today it opens up to a pedestrian plaza that extends back to NYPD Headquarters. The vault was modeled on Rome’s Palazzo Farnese. It was built to house municipal office space made necessary by the creation of Greater New York in 1898, and holds over a million square feet of offices. Today offices of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services, New York City Department of Finance, New York Public Service Commission, Manhattan Borough President, New York City Public Advocate, New York City Comptroller are within.

The statue “Civic Fame” is made of copper with a gild coat and is 25 feet tall. It was sculpted by Alfred Weinman, using model Audrey Munson, and is the second tallest statue in New York County, with only the Statue of Liberty surpassing it. The building’s sculptures and ornamentation are so rich I could devote an entire FNY page to it.

My one and only time in the building was October 23, 2006 when I appeared on the Brian Lehrer show on WNYC, which was located here at the time. Forgotten New York the Book had its greatest sales that day and attained the top 500 in Amazon. Some time later, Lehrer had me on a TV show he was hosting, and thankfully, video of that appearance doesn’t seem to have survived, though you can ferret out the radio appearance by googling it I’ve never heard it: I dislike my appearance in photos and my voice on recordings. Lehrer is still hosting his show daily at 10 AM.

On the right is the New York County Courthouse designed by John Kellum and Leopold Eidlitz and built in 1881. Once again the interiors are sumptuous, though I won’t get to see them unless I somehow join the NYC Department of Education, which occupies the building. It was constructed under the auspices of famously corrupt politician William “Boss” Tweed, who obtained millions from its construction through kickbacks and embezzlement. The building is unofficially known as the Tweed Courthouse, but not officially for a grifter who died in prison.

In 2002, it was thought that the Museum of the City of New York would relocate to this building, but new Mayor Michael Bloomberg moved offices into the former courthouse instead.

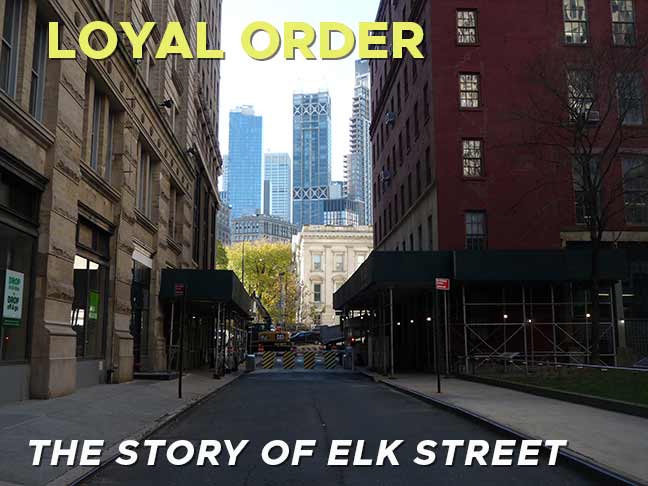

Elk Street runs for just two blocks, from Chambers north to Duane west of Centre, but I have always found its evolution to be of interest. It has had its present name for about 85 years, which is fairly young for a NYC street name.

First, there’s the curious nature of its street signs. That’s a lot of sign for just a short street. The reason for this is simple. Maroon colored signs mark historic districts, and this one marks the African Burial Ground Historic District. That’s a lengthy name that goes in the thin black band at the top of the sign. (I’ll discuss the burial ground presently.) As for the condensed font that creates so much room on the sign…

There’s no earthly reason to do that; these perfectly readable signs were switched out because of an ill-conceived policy instituted nearly universally in the 2010s that posited that upper and lowercase signs were more readable than all caps.

Who are you going to believe, federal regulations or your own eyes? Clearly, the second set of signs, now replaced, are eminently more readable, but not to suits in offices.

The Story of Elk Street

Elk Street’s story begins way uptown, with Lafayette Place, a one-block wide thoroughfare between Astor Place and Great Jones (East 3rd) Streets, that even today can boast some of NYC’s finest architecture. When the Williamsburg Bridge opened in 1903, additional traffic began flowing into Manhattan and traffic engineers (this was a couple of decades before Robert Moses began building his parkways and expressways) built two wide new streets; Kenmare, running east to west, and a southern extension of Lafayette Place that became Lafayette Street.

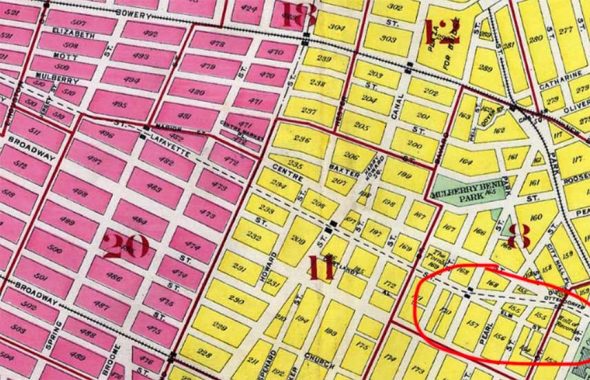

The new Lafayette Street had its own right of way south to Prince Street. At that point it took over the path of Marion Street (see this 1885 map) between Prince and Spring, and then Elm Street from Spring south to Foley Square. This left a short piece of Elm Street “orphaned” between Worth and Reade Street, the original southern limit of Elm.

This map shows then-new Lafayette Street and the remaining pice of Elm.

There are, of course, no elk on Manhattan island except perhaps in the Central Park Zoo. But there is the fraternal society the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, which evolved from a drinking club patronized by actors called the Jolly Corks which originated in the attic of an Elm Street boardinghouse in 1867, with the name change from Elm to Elk coming about in the late 1930s; it’s rumored that Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia was a member.

That’s not the end of the changes, though. Today, Elk Street runs in two noncontinuous sections from Chambers north to Duane. The section between Duane and Worth was eliminated decades ago, and today is occupied by the James Watson US Court of International Building. Thus, only one block of the “original” Elm Street remains, between Duane and Reade.

A “new” section of Elm appeared between Reade and Chambers, perhaps because the back door of the US Surrogates Courthouse, formerly Hall of Records, had to empty out onto a thoroughfare. This bit of Elk Street likely was “cut through” in 1907, when that sumptuous building was opened; the above map excerpt is from 1895.

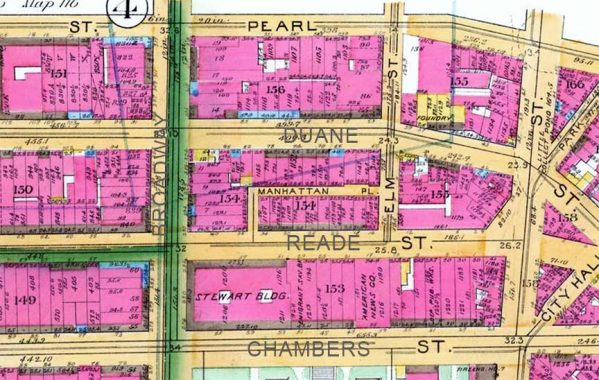

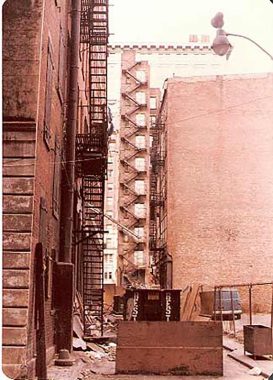

We see on the map a narrow alley west of Elk Street north of Reade Street labeled Manhattan Place. It was later known as Republican Alley and was L-shaped, turning south to Reade. As far as I can determine, these are the only two photographs in existence of it, snapped by Bob Mulero in the early 1980s. They alley was demapped in 1990 for new construction…that didn’t happen for reasons mentioned below. And the alley still exists, after a fashion, as I’ll explain.

The corner of Elk and Republican (what other website is going to reference that corner? I ask you) was lit by a Westinghouse cup mounted on a telephone pole, to which a park floodlight had been affixed, a weird hybrid. As you can see by this time the alley was debris filled and more or less doomed.

The “new” section of Elk Street between Chambers and Reade Streets is dominated by a parking lot, of all things, on its west side and the side entrance of the Surrogates’ Court. This is one of the most extravagant Beaux Arts buildings in NYC and one building I’d really like to enter one day to see the fantastic interiors. It was constructed from 1899-1907 (Horgan and Slattery and John R. Thomas) and was originally the Hall of Records. The building’s frontage on Chambers Street features several historical figures associated with NYC, some household names, some not: David Pietersen de Vries, Caleb Heathcote, DeWitt Clinton, Abram S. Hewitt, Philip Hone, Peter Stuyvesant, Cadwallader D. Colden and James Duane. The folks at Untapped Cities are able to get into places that I cannot, and thus, they have acquired interior photos that include its recently restored magnificent skylight.

Surrogates’ courts hear cases involving the affairs of decedents, including the probate of wills, and the administration of estates and trust proceedings.

The Elk Street side entrance has been used for outdoor shoots for a number of TV shows, including the longrunning Law and Order.

Police barriers prevent through traffic on Elk and Duane Streets to protect the Javits Federal Building a block north on Broadway between Duane and Worth.

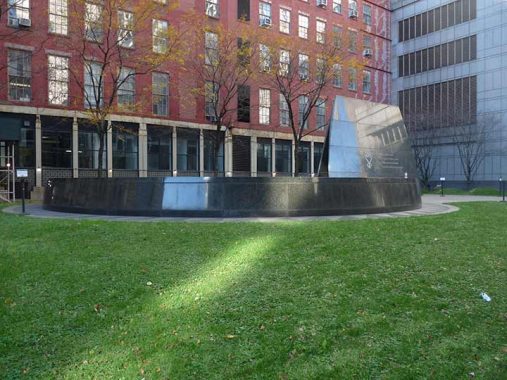

I had mentioned that Republican Alley had survived, after a fashion. Its old pathway is now a walkway on the south end of the African Burial Grounds Memorial.

African Burial Grounds Memorial

Manhattan recently gained its first new cemetery since the mid-1850s, although this one is hardly new…it’s just that its location was forgotten for centuries.

Workmen excavating a construction site on Duane Street east of Broadway in the fall of 1991 stumbled upon human remains interred in wooden boxes about 25 feet below street level. A search through property maps revealed that this area was a former burial ground for enslaved African Americans in the early 1700s.

The burial ground, when it originated, was just south of a body of water known as Little Collect Pond, a marshy area south of the much larger Collect Pond (a freshwater pond later made brackish by local industry; it was drained after 1816 by a canal that is now located in a sewer beneath Canal Street). A succession of dwellings and businesses rose on the site, and over time it was completely forgotten that it had ever been a cemetery.

When the interred remains were originally discovered, the federal government was building what was going to be the US General Services Commission Building, and had every intention to go ahead with its construction. After public pressure led by then- Mayor David Dinkins was brought to bear, however, the Feds reversed course and, in 1993, declared a small patch of land at the corner of Elk and Duane Streets a National Historic Landmark. The office building was modified to avoid the ground where the remains were discovered. More than 400 individual human remains were disinterred, along with artifacts also found there such as ceramics, animal bones and shells, and sent to Howard University in Washington, DC, for study. In October 2003, the remains were reinterred in the burial ground during a Rite of Ancestral Return ceremony. The site is now The African Burial Ground National Monument.

In 1940, these were the buildings that sat atop the African Burial Ground and were demolished in the late 1980s to make room for the cancelled General Services building.

Where Street View cannot go: the north end of Elk Street at Duane is considered too risky, given the presence of the Javits Federal Building, that Google Street View does not photograph it.

Speaking of Elks…

Local 878, Queeens Boulevard at Simonson Street in Elmhurst, Queens, was once the largest Elks Lodge on the East Coast with 60 rooms, bowling alleys, billiards, a ladies’ lounge, and a 50 foot bar, built in the teeth of Prohibition in 1924. The Elks don’t own the old place any more: it’s been sold to the New Life Fellowship, but the Elks remain as tenants. The Ballinger Company designed the granite, limestone and brick structure dominated by a now-verdigris-covered elk at the front entrance. For a couple of decades, Extreme Championship Wrestling (the old ECW, now folded into Vince McMahon’s WWE) bouts were held here featuring some of the legends of “sports entertainment” such as the Sandman and Mick Foley. The Elks Lodge is an official New York City Landmark.

Three decades ago, the lodge’s 6,600 members included some of the borough’s most prominent residents. The Elks raised funds for charity, held grand balls and otherwise reveled in their own brotherhood. “This was the place to be,” recalled Paul Reilly, 61, a retired police detective. “You’d have to fight to get near the bar.”

The struggle to hold on is becoming more difficult for Lodge No. 878, which retains its traditional, if not official, all-white membership. The need to compromise with reality has gotten to this point: the nation’s 2,250 lodges will vote next month on whether to allow female Elks. “Things wouldn’t be the same with women sitting at the bar,” said Bernie Dulke, 70, the lodge’s secretary and a professional church organist. “But I guess you got to roll with the times.”

The old fraternal organizations like the Elks, Masons and Shriners are becoming anachronistic. Its charitable and benevolent functions have largely been taken over by the government.

With its old-fashioned values, unapologetic patriotism and arcane rituals, Elkdom seems like a relic to younger generations. The lodge chief is called an Exalted Ruler, top-level officers are called Knights, and the induction ceremony is an elaborate ritual closed to outsiders. Initiates must be American citizens, have the endorsement of three members and “believe in the existence of God,” according to a promotional brochure. Women can only participate in Elk activities through the Ladies Auxiliary. Blacks were barred until 1973 and efforts to include them and other minorities since then, at least in Elmhurst, are open to question. [New York Times]

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

12/12/21

13 comments

The word in the lower left is “AIRFOAM”.

While there may not be any actual elk in Manhattan they’re within about 200 miles in central Pennsylvania,

Nice work Kev

There is a 1916 Bromley atlas plate that indicates the #1 Hudson edifice as the “Irving Building” and was the home of the Fidelity Trust Company. Newspaper searches indicate the company had been there as early as at least 1907.

Follwoing up, the Irving name for the building appears to have originated with the Irving National Bank which occupied the building beginning circa July 1903 after removing from a location on Greenwich Street. Fidelity Trust began operations May 22, 1907.

The Surrogate’s Court building bounded by Elk, Chambers, Reade and Centre also houses the NYC Municipal Archives, which has presented exhibits and public events in the past and is worthy of a visit (covid permitting). The structure is one of those (overly) ornate Beaux Arts edifices that were meant to speak solidity, justice and the rule of law back in an era when architecture shared a language in common with the populace. The building’s rotunda(which can be seen on google street view) rivals (IMHO) Grand Central, The NYPL main reading room and, I would guess, the old Penn Station in the category of vast and awesome public space.

The words are ‘airfilm shoes’ in the lower left of the sign. America’s only pneumatic shoe.

Very much enjoy this website, thanks!

Two comments. First, I stayed at the Cosmopolitan in 2016. It was probably one of the least expensive sleeps in the city, leaving aside SRO and other really poor quality locations. It was clean and quiet, with very small but usable rooms. All the other people coming to New York stayed in midtown and cabbed down to Tribeca. Being an old New Yorker, I chose this local hotel that was a walk or a subway ride to the venue. I had heard about the conversion to the Frederick, and note that the price has gone up dramatically. If it were still what it was, I’d have been interested in staying there again.

Second, the Elk St paragraph. I have been an Elk for 20 years. I knew about the origin in the Jolly Corks, but not about the located where they met. Also, not that the Little Flower was a member. So I have a new bit of trivia.

ALL the fraternal organizations are dying.American Legion,Odd Fellows,Moose,you name it.People are

joining gangs instead.

Ecco RIP, such a great restaurant-ate there 100 times easy.

Benevolent and Protective Order (BPOE).

https://www.crosbyarchives.com/new-project

Airfilm

There was also a very large swimming pool somewhere in the nether regions of the Elks building. Growing up in Elmhurst in the early 1970″s, I was always jealous of my friends who said they were “going swimming at the Elks” on a hot summer day.