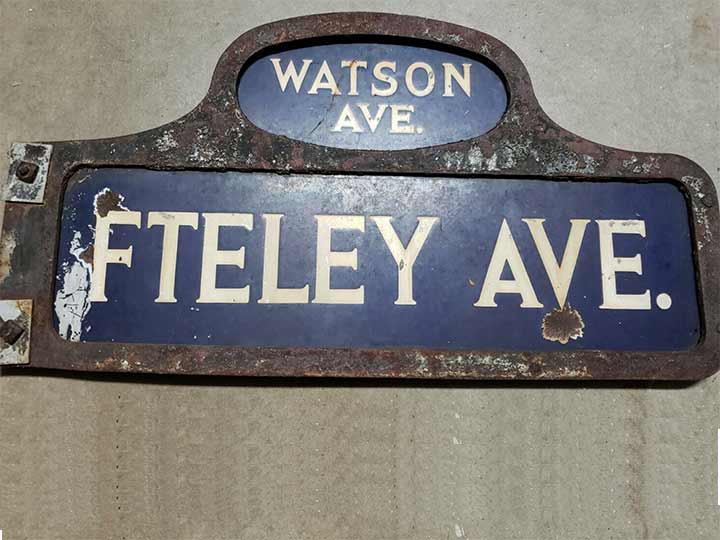

I was recently sent this image of a Fteley / Watson Avenues sign from the Soundview Bronx neighborhood. These navy and white signs were employed in Manhattan and the Bronx from the 1910s into the 1960s; Manhattan and the Bronx were the same county (New York County) until 1914, when the Bronx achieved countyhood. Coincidentally, navy and white are Bronx-dwelling New York Yankee colors as well.

When I first started poring over NYC street atlases in the 1970s, I was perplexed while fingering my dogeared Bronx Hagstrom because one of the streets in Soundview, just east of the Bronx River, was spelled Fteley. That had to be a misprint. No word begins with “FT”!

Which leads me to English orthography and spelling trends. Typically, English does not begin words with two consonants; the exception is with digraphs such as bl, br, ch, cr, dr, pr, pl, sl, st and more; these consonants’ sounds go together to produce one sound. Put simply, sometimes words will begin with two consonants that don’t jibe, such as cnidarian, bdellium, or pneumonia, but in cases like that the initial letter is usually silent. English has other quirks, such as a tendency not to end words with the letter “j,” which is usually rendered “dge” at ends of words except in loanwords like haj. I could go on with this, but you get the idea.

Another example of this sort of thing is (now, ex-) Mets pitcher Robert Gsellman, who says it Ga-ZELL-min. “Fteley” is pronounced as spelled, Fa-TELLY.

After awhile after looking at several maps, I ascertained this was no misprint and the name of the street was indeed spelled Fteley and later, I found out it’s pretty much pronounced as spelled, “fa-TEL-lee.” But what a strange name! I’d bet that no other place name in the world, or perhaps even word in any language, begins with “ft” without a vowel separating the two consonants.

t turns out the explanation for the name is somewhat unique, as well. There are groups of streets in Brooklyn named for the signers of the Declaration of Independence, NYC mayors in the NE Bronx, and even classical composers and astronauts in Staten Island. In Soundview, the streets are named for civil engineers! According to John McNamara in History in Asphalt, Alphonse Fteley (1837–1903) was chief designer of the upstate New Croton Dam, which helps supply NYC with its drinking water. Fteley was a French immigrant and is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery.

The story about Fteley signifying “Fort Ely” is “fake news” as there was never a fort in Soundview named Ely.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

12/26/21

8 comments

When the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey was looking for a new corporate name in the early 1970’s its first choice of Exon wouldn’t work because that was the name of the governor of Nebraka. Rather than start the lengthy naming process from the beginning someone suggested doubling the letter x to make Exxon. This turned out quite useful, as the process of ensuring the name had no vulgar or offensive meaning in any language – a complicated process in pre-Internet days – was simple because the only language in which the double-x construction occurs in Maltese.

Growing up in Connecticut I knew of some people with the unusual surnames of J’Anthony and M’Sadoques. The former was an early 1900’s attempt at Americanizing Gianntonio, while the latter (pronounced Massa-dokes) is an uncommon Portuguese name.

The surname “Foxx” exists in English as a proper noun – examples are Jamie Foxx (actor) and Jimmy Foxx (Hall of Fame baseball player in 1930s and 1940s).

I don’t know that the “fa-TELL-ee” pronunciation is the more intuitive one– it looks more like “FIT-uh-lee” to me, as in “Fiddle-dee-dee, Captain Butler…”.

But the street in Williamsburg, “Scholes St.,” has always fascinated me. Some people with that name pronounce it as if it were the plural of Scandinavian drinking toasts, and at least one as “shawls,” but at least historically, the name was pronounced by Brooklynites as if were “School-eez” Plus, the nearby Maujer Street, which looks French and thus might be more like “MO-zher,” is locally pronounced “MOY-jer,” I am informed.

Before Exxon changed its name, it was Esso. The (possibly appocrophyl) story that expains the name change is that “Esso” means “it won’t go” in some language (maybe Japenese?), not a great name for a gasoline! So the oil company wanted something that wasn’t too far off from the original Esso, but which would have no meaning in any language.

Standard Oil was broken up by the U.S. government in 1911. One of the companies was Standard Oil of New Jersey, Esso stood for S O, the initials of that company. There was also Standard Oil of New York which became Socony, then Socony-Vacuum after a merger. That name was changed to Socony Mobil, then Mobil. There are may other spinoffs from the original Standard Oil, but you’ll have to look them up.

there’s other areas of the bronx with a concentration of names with a commonality. soundview has a concentration of streets named after nineteenth century

writers, some completely forgotten, and the allerton area has a bunch of streets named after notable names in the nyc printing industry, for example.

I was flabbergasted to find out that Brooklyn had no blue

and white porcelain street signs

Actually, Brooklyn DID have the blue-and-white humpback street signs, but they were not installed throughout the borough. Flatbush Avenue had them, as did Seventh Avenue in Park Slope and a few other thoroughfares. But they were poorly maintained. When the original porcelain faded too much, the Department of Traffic would paint the signs black and repaint only the name of the main street, not the cross street. For the most part, the surviving Brooklyn humpbacks were replaced in 1957 by two-sided, embossed porcelain-coated steel signs. Those, in turn, were replaced in 1969-1970 by the current extruded 9″ high aluminum blades with an aluminum K bracket. Those signs employed the color scheme of white letters on black. Beginning in 1980 the DOT replaced those with the current white-on-green signs.