TIME for some more “gloaming roaming,” as this time I was stumbling around DUMBO on the day after Christmas 2021. It remains a favorite part of town despite the plethora of street fairs and flea markets that now seem to dominate it even in the coldest weather. Speaking of which, I briefly worked at a temp job in DUMBO in February and March 2015, which turned out to be the last consistently cold and snowy winter to date. And when it’s cold in DUMBO, it’s really cold as the wind off the water whips around those old cardboard factories, warehouses and coffee importing buildings and chills the skin as well as the soul. A few Mays ago I was in DUMBO on what was really the first hot day of the year and it was packed to the gills, as I learned with some dismay trying to get into the Shake Shack at Old Fulton and Water that I had no problems with when I was working that winter job.

After leaving DUMBO I made my way back to the subway complex at Barclays Center via Atlantic Avenue, on which I hadn’t been for a few years. I hope to cover some additional material from FNY’s previous comprehensive Atlantic Avenue page from 2007, from which I’ll borrow some material that’s not outdated here. That part of the walk was between 3 and 4 PM and already, darkness was beginning to settle in.

I began at the new Emily Roebling Plaza which was the final piece in the puzzle with Brooklyn Bridge Park, connecting its western and northern sections under the Brooklyn Bridge. There’s no doubt in my mind that the Bridge will be set off against a much different cityscape 150 years from now as it was when its construction began in 1870, when the tallest tower in downtown Manhattan was Trinity Church. What will Manhattan look like in 2172? Without a time machine, I’ll never know.

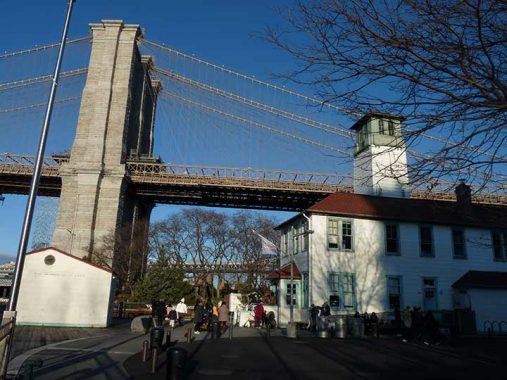

The first major bridge to span the East River was built between 1870 and 1883 and was designed by John Roebling, who died during construction after suffering a severe injury and contracting tetanus. His son Washington took over for him but contracted caisson disease after working in the compressed air under the East River; he directed construction from his home in Brooklyn Heights, with his wife Emily relaying his instructions to the on-site builders after getting up to speed in engineering. The Brooklyn Bridge remains NYC’s only major stone-clad bridge and only suspension bridge in the area with diagonal cables. These were thought to be necessary during construction but have been retained for their unique appearance.It formerly transported horsecars, trolleys and elevated trains, most or all of which have disappeared from the NYC scene.

I wonder why it took so long for NYC Parks to connect the two pieces of Brooklyn Bridge Park. I imagine it was because there may have been some complicated negotiations for what had previously been private property. Nevertheless, this spot beneath the Brooklyn Bridge has been a favored spot for outdoor photo shoots for wedding parties. It didn’t involve a lot of construction as it’s basically a large windswept plaza that involved the closure of New Dock Street. I prposely left the photos unaltered so you can get a good idea how dark it was in the shadows.

As always, you can get a larger view by clicking on any photo in a Gallery.

Emily Roebling (1843-1903), wife of Washington Roebling, assisted in the Bridge’s construction when her husband Washington (who had taken over the project from his father John, who had died of tetanus when his foot was crushed during construction) was himself struck down from caisson disease acquired when he was working beneath the East River bed and nitrogen entered his blood vessels. He then observed construction from the Roebling’s house with a spyglass and had Emily relay instructions to the construction workers. From her close association with her husband’s work as well as her own education, she knew engineering principles and with his help, she was able to explain his instructions to engineers. When bridge trustees wished to replace Washington Roebling a year before the bridge opened, her powers of persuasion were instrumental in keeping him on. She was on the first carriage to cross the Bridge when it formally opened in 1883.

The tugboat Jennifer Turecamo was built in 1974 by McDermott Shipyard Incorporated of Morgan City, Louisiana as the Marty Defelice for the Defelice Marine Towing Company of Lake Charles, Louisiana. When it was was acquired by the Turecamo Coastal and Harbor Towing Corporation of New York, New York she was renamed as the Jennifer Turecamo. presumably for a family member. In 1998 it was acquired by the Moran Towing Corporation of New Canaan, Connecticut, hence the distinctive M.

Skulking along the side of St. Ann’s Warehouse, a cultural venue and open air theatre adjacent to the plaza. Years ago, when DUMBO was still largely industrial, I was chased out by a security guard from what had been the Tobacco Warehouse originally built by the Lorillard tobacco producing family around 1860, that had its “guts” removed, leaving only the walls. I still furtively tiptoe around the place and am prepared to vamoose quickly just in case.

I jotted down what the sign says because there are times when I look at it and can’t read it! It says: “Purchase Department City of New York.” Apparently this agency is now part of the NYC Department of Finance. Apparently the sign is left over from when there was an office here.

One building remains from the Department of Purchase complex, #11 Water Street, constructed as a boiler house in 1936 (the sign appears as if it could also be from the 1930s). It has been tenanted the last few years by Luke’s Lobster, where the main menu item, lobster roll, costs $24-35. I have never been much interested in lobster and it seems like it would be an expensive snack if I were…

Mortals such as I are protected from the monied patrons of the River Cafe by a gate. The menu is price-free because if you have to ask you can’t afford it! It was founded by Michael “Buzzy” O’Keeffe in 1977. From its website:

The River Café has been celebrated with numerous accolades including: a Michelin Star, The Restaurant Hall of Fame Award, The “Ivy Award of Distinction” from Restaurant and Institutions Magazine, Distinguished Restaurants of North America Award (DiRoNA), The New York Parks Council Award, The Municipal Arts Society Award, The “Wine Spectator Award of Distinction” from Restaurants and Institutions Magazine, The Wine Spectator Award, selected by the French culinary guide, “Gault Millau,” as one of the five best restaurants in New York.

Glimpses of the fare and the interiors can be gotten from Yelp’s 2700+ photos. Note that in upscale restaurants, you pay for a lot of plate and not a lot of food.

#1-5 Old Fulton Street at the corner of Water is the home of that Shake Shack I was talking about, whose price points are more suitable for a copy editor and itinerant street photographer. The corner building was constructed as The Franklin House in 1835 and according to NYC Landmarks was “the most important dining saloon and hotel in the [Fulton Ferry] District during the 19th Century.” For years thr ground floor was occupied by Pete’s Downtown Restaurant.

The opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 caused Fulton Ferry, and the stretch of Fulton Street that led to it, to gradually decline. By 1939, the writers of the WPA Guide to New York City could say:

In the early part of the nineteenth century there was a cluster of houses, taverns stables, shanties, and stores at Fulton Ferry. The region, originally called “the Ferry;” later “Old Ferry” (when a new ferry was established at the foot of Main Street in 1796), blossomed into a pleasant residential neighborhood. The construction of the Brooklyn Bridge destroyed its beauty and the neighborhood became a slum. Fulton Street, in this section, is now a sort of Brooklyn Bowery, with flophouses, small shops, rancid restaurants, haunted by vagabonds and derelicts. Talleyrand once lived in a Fulton Street farmhouse opposite Hicks Street, and Tom Paine in a house at the corner of Sands and Fulton Streets.

For decades, the old ferry region at the beginning of Fulton Street was a tomb, dead and buried. The Brooklyn Bridge and the BQE shuttled traffic past it, and it was forgotten by most Brooklynites. For a time, it even lost its name, as the stretch was called Cadman Plaza West, even though this section doesn’t border the lengthy park built as urban renewal in the 1950s.

8 Old Fulton Street, formerly 8 Cadman Plaza West, and originally plain 8 Fulton Street. It’s the former HQ of the Brooklyn City Railroad Company; horsecars and then trolley cars began their runs at Fulton Ferry here, and the headquarters was conveniently located.

When I’m over here it’s hard for me to resist this shot of the Brooklyn Bridge and fireboat house constructed in 1924, the year the old Fulton Ferry, which connected this street with Manhattan’s Fulton Street, closed for good after 110 years in operation. Fireboat hoses were once hung to dry from the center tower. This also was the terminal point of the Fulton Street Elevated Railroad, which ran from here from the 1880s to the 1940s. An ice cream shoppe has occupied the ground floor for over a decade.

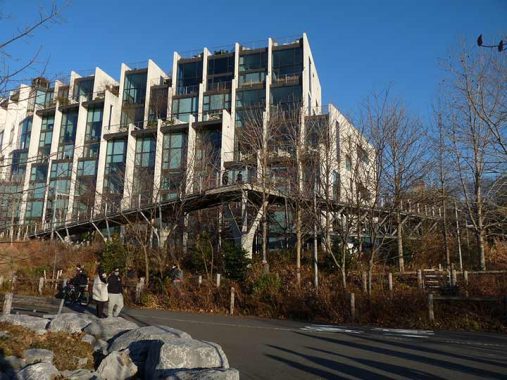

Brooklyn Bridge Park is the most recent major park to be constructed in the borough, opening in sections between Atlantic Avenue and Jay Street along the East River between 2010 and 2021, with Roebling Plaza topping it off. As with many recent NYC parks such as Governors Island, it’s mainly urban but pains were taken to truck in sod and grass to make it appear as natural as possible, even though this area has been completely “urbanified” since docks appeared along the East River in the 1800s; a railroad even connected them, remnants of which were still in evidence when I was exploring this area in the 1970s and 1980s. It features walking trains and a bicycle lane, which I would have preferred being kept separate from the pedestrian path.

The only access between Joralemon Street and Doughty Street allowing Brooklyn Heightsers passage to Brooklyn Bridge Park is the Squibb Bridge, originating in Squibb Park on the Columbia Heights cliff. Dr. E.R. Squibb (1819-1900) was a pharmacologist whose lab was located nearby. Squibb became a major commercial manufacturer; its slogan was ”the priceless ingredient in every product is the honor and integrity of its maker.” The company merged with competitor Bristol-Meyers in 1989.

Squibb constructed a large manufacturing plant at 25-30 Columbia Heights in the mid-1920s until most of the company’s plants were relocated to New Brunswick, NJ beginning in the 1960s. Subsequently the plant was purchased by the Jehovah’s Witnesses and became The Watchtower, recognizable by the large red neon sign overlooking the East River. The Witnesses owned a lot of property in Brooklyn Heights in the latter 20th Century including the Hotel Bossert on Montague Street.

The first Squibb Bridge was built in 2012 with a lot of “give” causing it to swing and sway like Sammy Kaye when crossed, and after a lot of complaints it was indeed found to be structurally deficient. A new bridge that was conventionally rigid was constructed on its original pylons and opened in 2020.

The Brooklyn Promenade, the uppermost of three decks along the cliff, was built as a compromise solution when Robert Moses wished to plow the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway through Brooklyn Heights. The BQE was routed along the waterfront on two levels, while the Promenade (technically called the Esplanade) was on the top, providing Brooklynites premier views of downtown Manhattan.

The BQE here was fundamentally flawed, construction-wise, and has deteriorated greatly. A plan to replace it completely and temporarily deck it over the Promenade has been shelved for now, however, as the Department of Transportation applied temporary palliatives to shore up the BQE before a new master plan can be devised, kicking the can down the road, as it were.

A square-rigged tall ship, Norway’s 107-year-old Statsraad Lehmkuhl, was docked in Brooklyn Bridge Park in late December, stopping over during a worldwide tour.

The tall ship, which is now a state-of-the-art floating ocean research laboratory, was built in 1914 by Joh. C. Tecklenborg as a training ship for the German merchant marine under the name Grossherzog Friedrich August, according to its website. It was taken as a prize after WWI by the U.K. and in 1921, it was bought by former cabinet minister Kristofer Lehmkuhl—hence the name. She was briefly captured by German forces in WWII, but it was donated to the Statsraad Lehmkuhl Foundation in 1978. Today, it is Norway’s largest and oldest square-rigged sailing ship and also the oldest amongst the large square-riggers in operation. {Time Out New York]

The west end of Atlantic Avenue at Furman Street as it crosses under the BQE. The avenue runs east to the Van Wyck Expressway and is about equally split between Brooklyn and Queens. The Long Island Rail Road ran trains from 1844 to 1859 to about this spot in an underground tunnel that still exists; the LIRR now runs from a terminal at Flatbush Avenue under and over Atlantic Avenue en route to Jamaica and points east.

An old metal post formerly used to carry trolley car wire now does duty as a sign holder at Atlantic Avenue and Hicks Street. Trolley rotes 15, which went along Flushing Avenue at the Navy Yard, and 28, which went to Erie Basin in Red Hook, were on this stretch of Atlantic. Another pole that served the 28 can se seen on Richards Street in Red Hook.

Expressway Laundromat at #142 Atlantic was likely founded after the BQE arrived in the 1950s. The sign is rendered in Helvetica Bold. On this walk I paid attention to sidewalk business signs, as I have been doing of late.

Meanwhile, the woodcut and gold leaf signage of the Sultan Restaurant and Cafe (that’s redundant, no?) is rendered in Goudy Text, a blackletter font that frequently comes up in Bibles or prayerbooks.

#19 Atlantic refers the passerby to the home of Homer and Langley Collyer, a brownstone row house on the corner that the two Collyer brothers had occupied for 38 years between 1909-1947. They had moved to the house with their parents, gynecologist Herman Collyer and his wife Susie; the doctor abandoned his family in 1919, passed away in 1923, and the two sons inherited their parents’ possessions and moved them into the 5th Avenue brownstone. Both brothers were Columbia University graduates, Homer earning a degree in admiralty law and Langley a degree in engineering, though he also apparently aspired to be a concert pianist.

After a series of attempts to burglarize the building by outsiders the brothers became increasingly reclusive, boarding up the windows, never throwing out any accumulated possessions and even setting elaborate booby traps to foil any intruder. Eventually they had collected numerous pianos, thousands of newspapers, and a model T Ford (living without gas or electricity, Langley had rigged up a generator from the car engine). Homer suffered a crippling stroke and lost his sight, forcing Langley to scour the neighborhood for scraps or cheap food, with water being obtained from Mt. Morris Park fountains. The brownstone became suffused in squalor with dozens of stray cats, rodents and other vermin. The two brothers were finally found dead in the apartment in 1947; Langley had fallen victim to one of his own booby traps while Homer died of malnutrition. It took weeks to find his body amid all the accumulated junk. The authorities followed the stench.

Items removed from the house included baby carriages, a doll carriage, rusted bicycles, old food, potato peelers, a collection of guns, glass chandeliers, bowling balls, camera equipment, the folding top of a horse-drawn carriage, a sawhorse, three dressmaking dummies, painted portraits, pinup girl photos, plaster busts, Mrs. Collyer’s hope chests, rusty bed springs, the kerosene stove, a child’s chair (the brothers were lifelong bachelors and childless), more than 25,000 books (including thousands about medicine and engineering and more than 2,500 on law), human organs pickled in jars, eight live cats, the chassis of the old Model T Langley had been tinkering with, tapestries, hundreds of yards of unused silks and fabric, clocks, fourteen pianos (both grand and upright), a clavichord, two organs, banjos, violins, bugles, accordions, a gramophone and records, and countless bundles of newspapers and magazines, some of them decades old. Near the spot where Homer died, police also found 34 bank account passbooks, with a total of $3,007.18. wikipedia

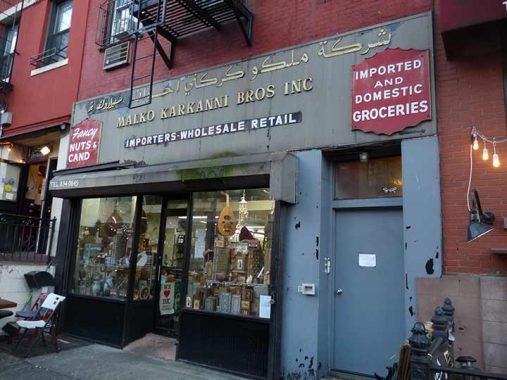

It’s probably not as cluttered inside #179.

Some of the shops on Atlantic Avenue have been selling Middle Eastern goods for 100 years, ever since large numbers of “Syrians” – many of whom came from what is today Lebanon, Iraq or Jordan – first started arriving in the United States. By the turn of the century, about 100 Arab families were clustered near the end of the avenue by the waterfront, a satellite of the main “Little Syria” on Washington Street in lower Manhattan. They enjoyed a rich cultural life that was in many ways like the one in the old country, with Arabic newspapers, coffee houses and festivals where they danced the old dances. In those days, some of the young men journeyed back home to fetch brides.

For many of the children and grandchildren of the immigrants living on or near Atlantic Avenue, its shops and restaurants were their only tangible link to the old country. Helen Uniss Khouri, for instance, was born in Brooklyn into a distinguished family from Abeye on the eve of World War I; she did not travel to Lebanon until the late 1940’s, and her sister Katherine Uniss Haddad never did get to go. As children, all of their images of the homeland were filtered through the memories of their elders or reflected in the transplanted life of the avenue. [Saudi Aramco World]

Given its old school signage Malko Kalkanni has been on Atlantic quite a few years.

Sahadi’s, 185-189, is the largest and most famous Middle Eastern food store on Atlantic Avenue, opening here in 1948. The business was instituted in 1895 by Abraham Sahadi on Washington Street in lower Manhattan. Unusually it occupies the ground floor of two separate buildings.

These buildings are in the eastern fringe of the Brooklyn Heights Historic District, the earliest so designated in 1965. All landmark district reports from the Landmarks Preservation Commission are online, and they’re simply scanned versions of the originals, thus the original typewritten 1965 report. While newer Landmarked districts get expansive, intensive reports on area histories with architectural details on every building in the district, the earliest such reports are not nearly so thorough. However, while the clickable LPC map indicates #185 was built in the 1840s and #187-189 anywhere from 1880-1895, exact records seem to be absent.

I’m familiar with the font used on the Damascus Bread and Bakery but I don’t know its name. It bears a resemblance to Arabic script and if often used in a Middle East context. For example, it was used on the cover of Santana’s Caravanserai LP in the 1970s.

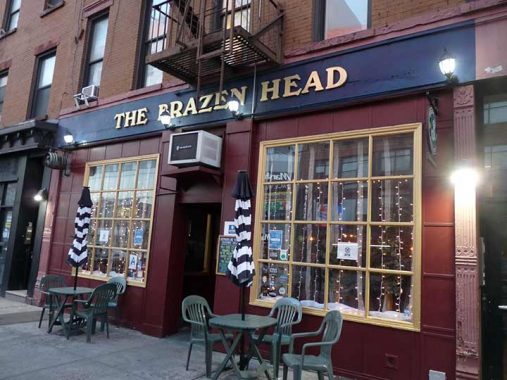

The Brazen Head has been the name of this Atlantic Avenue tavern at #228 since 2000. “Brazen head” refers to one of the world’s first robots, a “talking head” made of brass or other metallic alloys that would answer questions, apparently a myth originating in the medieval period. The bar, though, likely references The Brazen Head pub in Dublin, Ireland, established in 1198 and over 800 years old (so they say).

The Brooklyn House of Detention at Atlantic Avenue and Boerum Place was constructed in 1957 (as was your webmaster), replacing Miller’s Furniture Store. It has been reopened, closed, reopened and closed again multiple times; here’s a rare look inside. In 2022, though, the city seems serious about keeping it closed for good and actually demolishing it only to build another detention center twice as tall, with over 1400 beds, as part of the overall push to close the Rikers Island detention complex and replace it with neighborhood facilities.

The Boerum family arrived from Holland in the 1600s and produced prominent landholders and politicians in the colonial era. At Atlantic Avenue, Boerum switches from a narrow lane to an 8-lane behemoth also called Brooklyn Bridge Boulevard. This was accomplished around the time Cadman Plaza was built and Adams Street widened in the 1950s.

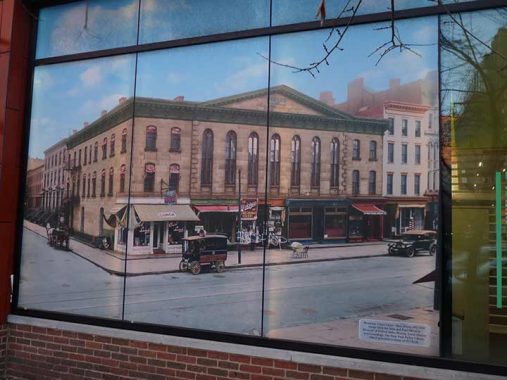

I’m not a patron of TD Bank but always look in the window when passing one, because the bank purchases historic photos or postcard views of the bank branch’s local area and places them in prominent spots, here depicting Atlantic Avenue and Court Street in the 1930s.

Though the detention center is closed until a bigger one can be constructed, the streets surrounding it are frequented by bail bonds businesses.

It looks like a synagogue but Talmud Torah Beth Jacob Joseph, a school at #368, moved out long ago and the 1917 space is now Deity, which calls itself an “all-inclusive, full-service Brooklyn wedding and event space.” I pointed the camera past the gate, but couldn’t get much. From the looks of things on Yelp it appears to be a standard issue catering hall, albeit a less glitzy one than normal, which I’d favor.

Patmos is a Greek island in the Aegean Sea, where, by Christian tradition, St. John experienced the strange visions that led him to compose the Book of Revelation (to Catholics, the Book of the Apocalypse). On Atlantic Avenue, it’s the name of the owner of this clothing store who vends her designs here, Marcia Patmos.

It looks older than it is, but the Belorussian Autocephalic Orthodox Church, at 401 Atlantic and Bond Street has been here “only” since 1902. St. Peter’s Episcopal Church erected a building here in 1850, and subsequently sold it to the Second United Presbyterian Church in 1863, who constructed this Gothic church in 1902. It has been spiffed up in recent years.

A couple of doors down is House of the Lord Church, #415 Atlantic. Pastor Herbert Daughtry has been involved in a myriad of causes over the years. This was originally the Swedish Pilgrims’ Evangelical Church, built in 1903, so the two churches were built about the same time.

When I was a kid my parents and I would go on lengthy trips of exploration on local buses, and one of the routes was the B-63 which ran down 5th and Atlantic Avenues to the waterfront. On the return trip I remember being amused by the factory building at #423 Atlantic near Nevins that was emblazoned “Ex Lax” over its front entrance, since even as a kid I knew that was the name of the “chocolate laxative” which was then advertised heavily on TV.

It was indeed an Ex-Lax factory, but it closed sometime in the 1960s. It was an early residential conversion in 1979, when I was still attending St. Francis College a couple of blocks away. A few years ago I went on an Open House New York tour through one of the ultramodern residences that have been carved out of the old poop loosening factory, which once kept a “staff” of monkeys on hand for product testing. The monkeys’ old quarters, in which they were kept in cages, has been incorporated into one of the apartments.

There was a time, a few years ago, when the Hollow Nickel at #494 Atlantic was the go-to venue for my merry band before we switched it to Faile near the Garden because it was near Penn Station, but who knows, we may switch back as more of us work from home or retire. Still a haul for me from Little Neck, though.

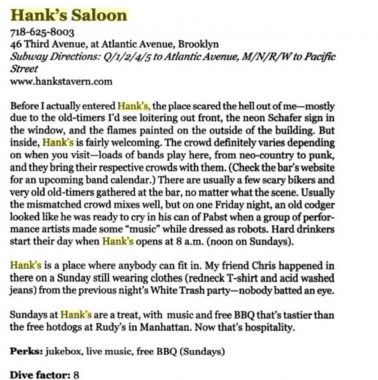

Hank’s Saloon, 3rd Avenue and Atlantic, used to be one of Brooklyn’s only dive country and western bars. Well, maybe the only one. Its original location is currently biding its time as a billboard for Marjam, the construction company. The original Hank’s moved to Adams and Fulton Streets in 2017, but that site, too, has closed. We await Hank’s next reincarnation, if any.

Since I never troubled Hank’s (regretfully) I’ll let Wendy Mitchell describe it, from the first edition of New York City’s Best Dive Bars (Ig Publishing, 2003):

The 34-story, 512-foot tall tower, One Hanson, which can be seen from western Queens, southern Brooklyn, and eastern Manhattan as well as the Bronx (from the Whitestone Bridge) was built as the offices of Williamsburg Bank from 1927-1928 by architects Halsey, McCormack and Helmer. The firm’s Robert Helmer wrote at the time that he was seeking to build a “cathedral dedicated to the furtherance of thrift and prosperity.” It was constructed in a style architectural experts call Byzantine Romanesque, with Art Deco touches, and has one of the largest 4-faced clocks in the USA. For most of its existence it was home to offices of the Williamsburgh Savings Bank, but also a large collection of dentists and oral surgeons (I have had 3 done in the building) for which I’ve nicknamed it The House of Pain.

The vaulted marble banking hall on the ground floor with 63-foot vaulted ceilings, 40-foot windows and elaborate mosaics is a must-see experience for every NYer. A couple of good images of the banking hall can be seen at Skylight NYC One Hanson, which developed the building’s apartments — it was largely converted to condominiums in the early 2000s.

It no longer is the height champion of Brooklyn, but it still retains the title of King of All Brooklyn Buildings.

I am not a creature of darkness, so with fading sunlight it was time to hustle back to headquarters. To do this I boarded the IRT for Penn Station at the Atlantic Avenue station, once the terminal for the original Brooklyn IRT when it was completed in 1908. It still retains the Beaux Arts elements that stations designed by Heins and Lafarge boasted. Since 1908 the station has been joined by two BMT lines as well as the LIRR, making it one of NYC’s largest transit hubs. Till recently it was a complicated mess, but the MTA has done its best to make sense of the layout.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

3/13/22

8 comments

The final resting place of the Collyer Bros. was on upper 5th Avenue in Manhattan. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Collyer_brothers

Atlantic Avenue, as well as Pacific and Dean Streets, around 3rd and 4th Avenues, housed numerous Irish during the famine years. My husband’s ancestor, a Civil War veteran and local stonecutter, lived in 547 Atlantic Avenue during the 1870s, a building that is still standing today despite how close it is to the Barclay’s area.

Thanks for this in-depth look at DUMBO, Brooklyn Bridge and surrounding neighborhoods. I too find some fascination with signage and fonts. Growing up in NYC with its myriad of show posters, subway tile signs, shop signs, etc inspired a career in graphic design. Retired now after 50 years. The font used for the Damascus Bread and Bakery sign is called “Caliph”.

The site of the now-vanished bar you call Hank’s I recall had an earlier incarnation as a sleazy looking hangout with a different name but I can’t call up that name, I think it began with A. Does anybody else remember it? I was in there once and found it to actually be very friendly. I had been down to Baltimore on my Ducati motorcycle in 1968, a long and tiring trip, to meet a lovely blonde for a date to see the latest release, Yellow Submarine, and then go to a motel. I sold a pint of my blood to raise the eight bucks for the motel. And then a long ride back to Brooklyn, it began to rain, I was soaked. And right there on Atlantic Avenue my chain slipped off and now I was stuck. Happened right on that corner, I went into that bar for shelter and to use the phone. Called my father who came by with his car to pick me up and put my motorcycle in the open trunk and drove me back to my basement apartment in Marine Park. Sat at that bar warming myself up waiting for Pop and the bartender and patrons in this dark and dingy little dive were very friendly.

I was able to find the name of that place before it was Hank’s in an article in the Brooklyn Eagle. It was Doray Tavern, said to be the favored hangout for the sure-footed Mohawk ironworkers who had a little community nearby, the guys who built the Verrazzano Bridge and other landmarks. You can google anything, I think the internet is just wonderful for research after all those years I spent doing library research leafing through catalog cards. https://brooklyneagle.com/articles/2019/05/31/the-beloved-hanks-saloon-is-closing-for-the-second-time-in-a-year/

My father’s father circa 1915-1920 owned a grocery store at 311 Atlantic Ave., where they also lived. I’ve found an article online from the Brooklyn Times Union in 1919 detailing how an alleged “War Profiteer” was arrested for selling sugar to my grandfather at $0.33/lb.

It kills me what they did to”Dumbo”

Does anyone remember the greasy spoon diner under the Brooklyn

Bridge that was for the longshoreman so it was only breakfast and

lunch?Saw it last in 1971.

Just below the pedestrian walkway in front of either Bridge tower is a

emergency trap door that goes down to a door to the interior of the

tower.I think you can take spiral stairs up to the top of the tower from

them.Probably also to the Saddle Room,where the huge sadddle castings

for the big cables are located.In his book The Great Bridge David Mccukough

lo seems to be pretty vague about this construction detail of the bridge.How

we loved to play on the bridge when we were kids.Like a giant Monkey Bars

in the playground

Love the Statue of Liberty shot!