It was a pleasant day in May and I had completed the Astoria Village leg of my planned excursion that included AV, the west end of Astoria Park, and then following Ditmars Boulevard east as far as the Airline Diner and then back to the N train. Last September a walk down Ditmars almost led me to a fight with security at The Pomeroy restaurant as he inexplicably didn’t like people snapping pictures of the restaurant exterior. A nose to nose argument ensued, and the threat of violence was implicated. An email to management was fired off, and an apology and the offer of a meal was proffered, but I have skipped. This walk was less eventful, but I kept the camera sheathed when passing by the Pomeroy.

I am not sure if Queensites fully appreciate that they can get two magnificent bridge views for the price of one (free) in the western end of Astoria Park, with both the Queens to Randalls Island leg of the Triboro Bridge and the older Hell Gate Bridge on full view.

Though a Harlem and East Rivers span from northern Manhattan to Queens had been talked about since the Queensborough (Ed Koch) Bridge had opened in 1909, it took enormous political will and engineering expertise to connect the Bronx, Queens, Manhattan and Randalls Island, and though ground for the bridge was broken in 1929, substantial work didn’t commence until 1934, with the complete bridge opening two years later. The complete story of the Triborough Bridge can be found in Sharon Reier’s excellent book, The Bridges of New York (Dover, 1977).

The main span is 1380 feet (421m); it is the longest of the Triborough’s three spans, and the total length including approaches is 2780 feet (847m). Unlike the other two spans, it contains just one narrow sidewalk, on the north side. The towers are 315 feet (96m) in height. The architect, Othmar Ammann of Switzerland, built most of the City’s great bridges of the 20th Century: The George Washington; Triborough; Bronx-Whitestone; Throgs Neck; and Verrazano-Narrows.

In 2011, the bridge’s 75th anniversary, I took a well-attended Forgotten NY tour across two of the three spans.

In Astoria Park, I spotted the newest variety of lampposts used to light park paths, known officially in the Department of Transportation as the Flushing Meadows Pole as mentioned on Page 177 in the DOT Street Design Manual. The lamp fixture, though, seems to be a variation on the one seen in the handbook.

Tucked away in Astoria Park is its World War I monument, on the park walkway north of the Triborough Bridge and facing Shore Boulevard and the East River. 101 residents of Astoria and Long Island City perished during the war, which took place in Europe between 1914 and 1918. The memorial was commissioned in 1926 by a group called the Long Island City Committee, designed by architecture firm Ruehl and Warren, and the artwork, which seems to have suffered some weathering, was by sculptor Gaetano Cecere, whose other work can be found in the U.S. Capitol, Smithsonian Institute and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Biblical quotation is from John 15:13. The famed Astoria Pool, built a decade after the memorial, is just behind it.

There’s a number of “hidden” NYC infrastructure items hidden along Shore Boulevard, which is why I was here. As the green bike lane was deemed not sufficient, motor traffic except for ice cream trucks and the like was recently banned from Shore Boulevard as it skirts the east side of the East River and the west side of Astoria Park.

On June 15, 1904, the General Slocum, an excursion vessel on the way to Long Island for a church picnic outing, burst into flames in the East River. Over 1200 lost their lives.

Slocum Captain William Van Schaick drove the vessel toward North Brother Island, one of two small islands in the East River between Port Morris, Bronx, and Riker’s Island.

Van Schaick’s decision to beach the Slocum on North Brother was a dubious one; there were closer piers at Port Morris, the southeastern tip of the Bronx. Since there were numerous wooden piers and oil tanks there, however, some historians say Van Schaick took the only course of action available to him. More outrageous was the fact that the Slocum was hardly prepared for any mishap as corrupt inspectors had declared the Slocum seaworthy despite:

–The ship’s six lifeboats were not only tied down but painted to the deck

–Life belts were nailed to the overhead in rusty wiring and were 13 years old; they had deteriorated such that the cork had turned to powder, dragging down anyone who wore them to the bottom; some were filled with cast iron

–Fire hoses were rotten and frayed and burst apart when water was run through them

–Some of ship’s crew panicked

Steamboat company officials were tried but not convicted, even though proof was obtained that the owners had bribed the inspectors. Only Van Schaick served any prison time, 3.5 years at Sing Sing. He was pardoned by President Taft in 1912.

The Parks Department has affixed a sign at the approximate spot at which the Slocum caught fire in the East River.

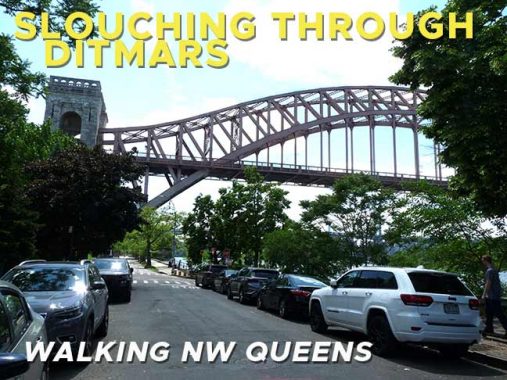

The Hell Gate Bridge was the final piece in the puzzle of running railroad trains into Midtown Manhattan. The tubes connecting Long Island with Penn Station opened in 1910, and Hell Gate Bridge, connecting Long Island with the mainland, opened in 1917 as the lengthiest steel arch bridge in the world until surpassed by the Bayonne Bridge in 1931. “Hellgat” means ‘beautiful strait” in Dutch, but lived up to its English transliteration as an extraordinarily dangerous stretch of water due to conflicting currents of the East River and Long Island Sound, as well as a great deal of rocks that made it treacherous for shipping until the rocks were dynamited into rubble in the late 19th Century. The construction was overseen by Gustav Lindenthal, who worked on the Williamsburg and Queensboro bridges as well. In the mid-1990s it was painted a deep maroon, which the sun has faded to light magenta.

Sharon Reier in The Bridges of New York:

The 1,017-foot long arch, of course, is only the keystone is a system of water and land crossings that in itself was the largest of its type in the world. The whole length of the structure, including the arch and approaches from the abutment on Long Island to the abutment in the Bronx is 17,000 feet, or considerably more than three miles…

….few people, even passing as close to it as the Triborough Bridge, realize the colossal size of the various parts. No existing large span bridge had ever been designed with such huge parts. Some of the steel members were more than twice as heavy and bulky as any parts ever hoisted in previous bridge construction… The heaviest bottom chord section weighed 185 tons. They were made of a recently developed material — carbon steel — which gave greater strength for its weight. The bridge, it was said, used more steel than the Manhattan and Queensboro Bridges combined.

There are a number of memorials and memorial plaques found on Shore Boulevard, facing the river, where few can see them. This one marks the course of the New York connecting Railroad, which runs from the Fresh Pond Yards in Glendale Queens north through Woodside and Astoria, crossing the river via the Hell Gate Bridge to yards in the Bronx. Passenger Amtrak service also uses the Hell Gate Bridge.

Way back in 2004 I walked the NY Connecting Railroad Queens trackage in an outing with the The New York Connecting Railroad Society in a tour led by the late great RR/Newtown Creek photographer Bernard Ente.

This is the beginning of Ditmars Boulevard, at the East River and the north end of Astoria Park. The name Ditmars, or Ditmas, appears more than once in the NYC street directory. The Bronx has a Ditmars Street in City Island, there’s a Ditmas Avenue in Kensington, namesake Ditmas Park and Brownsville, Brooklyn; and here in Astoria, Ditmars Boulevard, named in honor of Abram Ditmars, first mayor of Long Island City, NY who was elected in 1870 (the city became a mere neighborhood when Queens became a part of Greater New York). His ancestors were German immigrants who settled in the Dutch Kills area in the 1600s. Ditmars Avenue was laid out in the late 1800s and during the 1910s, during Queens’ big changeover to a consistent street numbering system, many busy roads were renamed Boulevard, and Ditmars was one of them.

Ditmars Avenue was originally laid out as far as Cabinet Street (49th Street) at the vanished Bowery Bay Road (as seen on this 1909 atlas), and was gradually extended, in fits and starts, and now skirts LaGuardia Airport on its way to join Astoria Boulevard at about 111th Street.

Found here at Shore Boulevard and 21st Drive is a short masted version of the old-style mastarm used to hold fire alarm indicator lamps. By 2014 this lamp was no longer being serviced, as the small “top hat” on top of the main luminaire, installed several years ago, now functions as the indicator. The city hasn’t removed the old lamps, but no longer services them or replaces the bulbs. Finding the orange covers will be more and more difficult in the coming years, as they just fall off and are discarded, and the masts will vanish as the poles they are on are replaced.

Gloria D’Amico is honored at Shore Boulevard and 21st Drive. The Astorian (1927-2010) served as Queens County Clerk for 19 years and was a leader in local Democratic Party affairs. She teamed with Ralph DeMarco (1908-1977), who has a northern strip of Astoria Park between the Hell Gate Bridge and 20th Avenue along Shore Boulevard named for him.

in this photo we are looking toward Randalls Island and the truss bridge that takes Amtrak and freight railroads across a narrow stream called the Bronx Kill that separates the island from the mainland. In 2015, a pedestrian and bicycle path was built beneath it, and I used it to walk from Port Morris through Randalls Island to the Upper East Side in 2016.

I have always wanted an apartment with a park view, like these on 19th Street and Ditmars, facing Astoria Park. (When I lived at #654 73rd Street in Bay Ridge from 1982-1988, I could see McKinley Park across the Gowanus Expressway if I raised my bathroom window).

I continued down Ditmars, but I am not going to list everything that interested me–since I have already covered it on this FNY page from July 2009. Today, I was mainly out for exercise…

A concrete ramp with a pair of gateposts can be found at Ditmars Boulevard and 26th Street. St. John’s Prep High School can be seen in the background. This is apparently what remains of River Crest Sanitarium, established here in 1896. It had closed by 1961, replaced by Mater Christi High School, now St. John’s Prep. The above two postcards show it in 1920 and 1940.

St. John’s Prep is a Catholic high school located on Crescent Street between Ditmars Boulevard and 21st Avenue. It was named for St. John the Baptist, a central figure in the Gospels, a preacher who foretold of the coming of Christ and in the Gospel of St. Mark was beheaded at the behest of Salome (rendered in the gospel as Herodias), a daughter of King Herod.

The school had its origins in 1870 as a prep school for St. John’s University, but today there is only a marginal affiliation between the two schools. Located in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, the original prep school was all-boys and closed in 1972. However, later on in the 1970s Mater Christi High School (constructed on Crescent Street in 1961) merged its boys’ and girls’ divisions and took over the name St. John’s Prep in 1981.

I almost never make a Gallery this large, but I was entranced by the colorful plaques mounted on the side of one of the school buildings. I had to shoot through the chain link fence to get them. There are the usual ecclesiastic symbols, including a crowned cross, the chi-rho (which is taken from the first two letters of “Christ” in classical Greek) with alpha and omega (Christ referred to himself as the Alpha and Omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet in Revelations, known to Catholics as The Apocalypse). There are symbols of the arts, math and science departments, the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, the dove representing the Holy Ghost and tongues of flame symbolizing Pentecost, and much more. The plaques were likely produced by St. John’s Prep students.

Steinway Reformed Church, Ditmars Blvd. and 41st Street, was built in 1891 as the Union Protestant Church but likely switched monikers after piano man Henry Steinway donated a pipe organ. It’s likely Steinway also built the church as a place of worship for the workers in his factory — he already had built workers’ housing two blocks away on 20th Avenue between 41st and 43rd Streets (seen in Part 1). To this day, the Steinway name is still appended to the church.

For a grand sweep of Astoria, including the “Steinway Village” mentioned above, check this FNY series.

The New Orsogna Club is from a tradition originating with immigrants from the small town of Orsogna, Italy who arrived in the USA in the first decade of the 20th Century. The original Orsogna Mutual Aid Society can be found on 18th Street in Astoria Village as well as this one, at 45-09 Ditmars Boulevard. Its fascinating story can be found here.

I ended my eastern progress at the Arline Diner/Jackson Hole, Astoria Boulevard and 70th Street, a block south of Ditmars.

Hard to believe it but I have not eaten here, Astoria Boulevard North and 70th Street at the classic Airline Diner, now a branch of the Jackson Hole burger chain, since September 2006, the same week the ForgottenBook came out, while being interviewed by ForgottenFan Jen Kitses for the Brooklyn Rail weekly. It occurs to me that I gave the Airline burger short shrift on my FNY Finer Diners page (most of the diners on it are gone now–I wrote it in 2001!). I take it back since the 2006 burger was first rate, in my opinion. The Airline has kept just about all of its old decor, including 1960s-style jukeboxes on every table, the ones with pushbutton controls and printed labels showing A and B-sides. Adam Kuban of Serious Eats (formerly A Hamburger Today) gave the Airline middling marks, but you’re here for the ambience as much as the meat.

The Airline is a Mountain View and has held down this locale on Astoria Blvd. since 1952. As you probably know, the diner along with (now closed because of fire) Goodfellas/Clinton Diner, is in scenes of the Scorsese mob epic Goodfellas. East of here, Astoria boasts the Buccaneer Diner and the vanished Deerhead Diner.

Wait a minute. We’re on 70th Street? We were just on 49th! In north Astoria, the streets skip over twenty blocks because of a change in the street grid. Astoria’s streets are skewed SW to NE, while in the rest of Queens, they run more north to south. If you look at the map, the Sunnyside Yards form a barrier between the two grids, but here, they meet with Hazen Street serving as the divider. West of it you’re in the 40s, east of it, you’re in the 70s. South of here, Broadway serves as the changeover point between the grids.

I never noticed this model locomotive adjacent to the diner. I wonder how long it has been there.

I decided to walk 23rd Avenue back toward the N train. Just the exterior basics at Joe’s Garage Bar and Grill at 23rd Avenue and 45th Street, which opened in 2017 at the former Astoria Building Supply. Unfortunately it seems closed for now and I hope it’s not a Covid casualty.

Just a short distance away on 23rd Avenue is this faded painted sign for The Alps Provision Co. , a meat wholesaler.

Astoria Silk Works, Steinway Street at 23rd Avenue. Swiss immigrants the Mattman Brothers constructed a silk works comprising several acres to manufacture cloth in 1888. Jacob Ruppert, the beer baron and Yankees owner, was once the company’s chairman. The company purchased several acres upstate near West Point in the 1920s, and the Astoria silk works closed down in the 1950s, leaving just this brick building and a smokestack. Today, recording studio Astoria Sound Works is in the building.

I passed beneath the Hell Gate Bridge on Shore Boulevard and after circling back I am doing it again, here at 23rd Avenue and 35th Street. Of course i would notice the working Westinghouse AK-1o lamp, complete with LED bulb.

The Queens branch of the Muslim American Society is located at the Dar-Al-Dawah Mosque in a former Christian church at 23rd Avenue between 33rd and 34th Streets. The building looked similar in 1940, when it was a Christian church of some type.

I am fascinated with giant masonry arches, which ton me look otherworldly. FNY has mentioned Astoria’s Hell Gate RR arches on numerous occasions.

Before getting on the train, I noted this “Brownie” New Gumball sodium lamp, which are now being repalced by LED models.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

7/24/22