By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

On the map, the Bed-Stuy neighborhood of Brooklyn appears nearly unchanged since the mid-19th century, with few superblocks, and not one grid-defiant street. But on these blocks there are many architectural standouts that speak of its history.

DeKalb Avenue is one of Brooklyn’s long roads, running for 4.2 miles from Albee Square in downtown Brooklyn to Linden Hill Cemetery three blocks inside Queens. Its namesake is Baron Johann de Kalb, a German-born military commander who served in the French and American armies. He was killed in 1780 at the Battle of Camden in South Carolina.

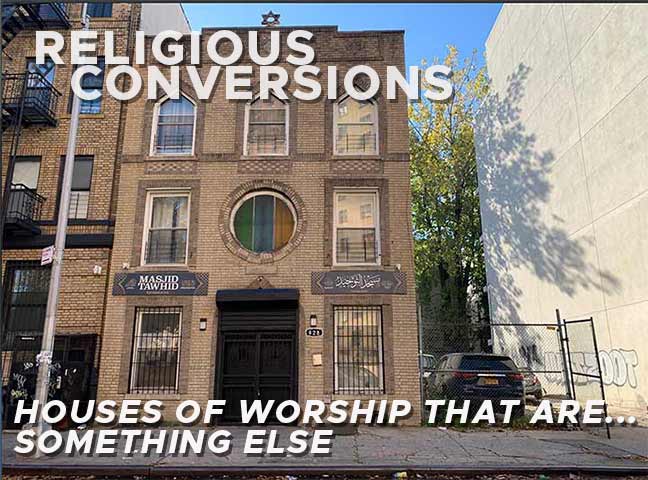

A common sight in inner-city neighborhoods are former synagogues that became churches after their Jews moved on. At 928 DeKalb Avenue (between Marcus Garvey Blvd. and Lewis Avenue) is something different: Masjid Tawhid, which has a Star of David atop its building and a round window above the entrance. In Arabic its name translates to Oneness, in reference to God. Most of the worshippers here are West African immigrants and African Americans.

Seeking to learn more about its Jewish history, author Ellen Levitt was surprised to hear that the prayers were in Arabic. On her last visit inside 928 DeKalb, the building hosted the Church of God in Christ, a historically African-American denomination rooted in the Pentecostal tradition.

I could not find information on when this building became a church, as city online records reach back only to 1968, showing a succession of churches here. A tax survey photo from 1940 shows an elaborate entrance that has since been simplified. The Hebrew lettering provided its name: Eitz Chaim Anshei Lubin, an Orthodox synagogue.

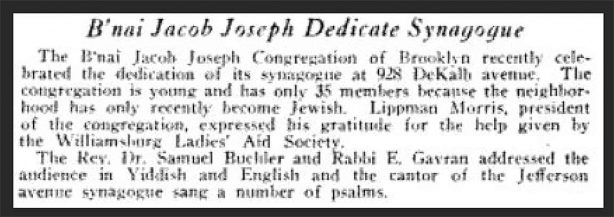

Going back further, American Jewish Chronicle notes that it was dedicated in 1916 with 35 founding members under the name B’nai Jacob Joseph d’Brooklyn. During the Prohibition, many religious individuals made money by selling sacramental wine to people outside of their congregation. In 1917, one such member, Abraham Shirro was arrested for selling brandy without a license on Rosh Hashanah. In a 1959 report, this building was still a synagogue, among a dozen in Bed-Stuy that would be gone within a decade. So far, it is the only synagogue-turned-church-turned-mosque that I’ve found in this city.

Looking west on DeKalb Avenue one sees a mix of architectural styles: an uninspiring NYCHA tower, walk-ups with cornices, and post-millennial condos with seemingly useless “Juliet balconies.”

On the east end of this block is FDNY Engine 217, a firehouse dating to the 19th century. If this building could talk it would speak about its history of battling blazes in wooden houses, brownstones, and NYCHA Eleanor Roosevelt Houses. This set of nine low-income high-rises does not break up the street grid. Among its famous former residents are the rapper/actor Yasiin Bey (formerly Mos Def) and rocket scientist Dr. Aprille Ericsson.

A couple of blocks to the north of this firehouse is the former campus of St. John’s University, where the architecture hints at the college’s presence in Bed-Stuy from 1868 to 1954. That year it relocated to its Queens campus, which I documented in detail in 2016.

At the corner of Lewis Avenue and Hart Street, the Bedford Stuyvesant New Beginnings Charter School has the Collegiate Gothic style of a CBJ Snyder public school, but a closer look at the building reveals its religious past. Completed in 1927, it was originally the Moore Memorial Building, named for the Very Rev. John W. Moore, the president of the college from 1906 to 1925. It hosted St. John’s Prep High School until 1972, when it relocated to Astoria.

On the main entrance, one can see the emblem of St. John’s University with its Latin name on the left side. The Gothic niches seem to be designed for statues that never arrived [or removed after the school was no longer church-affiliated – ed.]

The former parochial school building next door is now a set of apartments but the cornerstone “A.D. 1932” hints at its past as do the words above the entrance.

Across the street, the former administration building of the college was partially demolished as it underwent a residential conversion. Its design maintains a historical appearance. Without the crucifixes, statues, and Latin inscriptions, would future residents know that this used to be a Catholic college campus?

Looking south from Willoughby Street, one sees the inside of the building whose classrooms and offices will soon become someone’s bedroom.

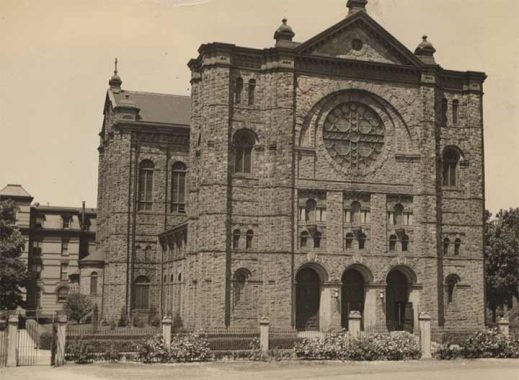

The main building on this campus was the massive church of St. John the Baptist, completed in 1894. It was built to stand for centuries at a time when Bed-Stuy experienced an influx of Catholic immigrants. Its architect Patrick Keeley was a prolific church designer, with examples along the East Coast. At the height of its popularity, it hosted 12 masses each day! Its designers reflected the diversity of Catholic immigrants at that time: Keeley was born in Ireland, muralist Leon Dabo was from France, and stained glass designer Otto Heinigke was the son of German immigrants.

With the decline of Bed-Stuy in the 1950s, followed by three decades of rising crime and disinvestment, the stained glass windows were replaced with cinder blocks; the piazza in the front that served as the college’s sports field was parceled out to developers, and the cavernous sanctuary could no longer be used.

Looking east from the main entrance to this church, the former piazza is a tight set of backyards that provide a suburban lifestyle deep inside this urban neighborhood.

Looking at the church from Hart Street, it is odd to see it facing a set of uninspiring single-family townhouses. Their design is reminiscent of Charlotte Street in the Bronx, both were built in the 1980s, when there was little expectation that inner-city neighborhoods would regain their populations. So instead of apartments, developers built low-density homes.

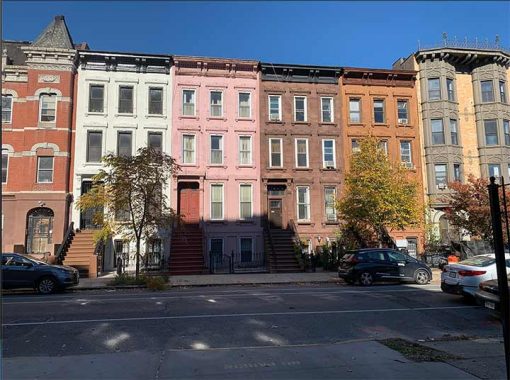

On the north side of the church is a more familiar Brooklyn streetscape, where each of these 19th century architectural survivors has a distinct color and design feature. Neither these buildings, nor the church, the former parochial school, or mosque, are landmarked. That’s why their unchanged appearance is worthy of a Forgotten-NY essay.

On my visit to the church, there was scaffolding and men at work, giving me hope that a church designed to last an eternity will continue to serve its faithful in Bed-Stuy.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

11/5/22

8 comments

I lived at 699 Willoughby Avenue from 1948 to 1954, between Sumner (now Marcus Garvey Blvd) and Throup. here was a synagogue, located at 730 Willoughby Avenue, Young Israel of Williamsburg. 730 Willoughby Avenue is now home to Beth Shalom Ethiopian Hebrew Congregation,

On Wikipedia, there’s a list of present and former Young Israel synagogues. I’m one of its editors.

It’s evident from Google Street View that the church –> mosque conversion is a recent one. The church sign is up in the November 2020 view, to the replaced by the mosque sign in July 2021. Of course it’s possible that the church ceased functioning some time prior to the sign removal.

St. John The Baptist looks like Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal in Ridgewood, Queens.

https://en.everybodywiki.com/File:OL_Miraculous_Medal_RCC_Bleecker_St_60th_Pl_jeh.jpg

St. Vincent DePaul Church on North 6th Street in Williamsburg morphed into apartments.

https://photos.zillowstatic.com/fp/d1012db3984573e0f9616bf9b721914a-se_extra_large_1500_800.webp

There are many, many former synagogues in the Bronx that are now churches or used for other purposes.

same for old synagogues on LES, now repurposed.

12 masses each day?! A Catholic minyan-factory!