Continued from On the Eighth Day

On this early summer day in June 2022, I traveled down 8th Street in Park Slope (with a detour to 9th) and then up 7th Avenue and then to downtown Brooklyn, with the latter changing rapidly, almost by the day, with new “supertall” residential towers. Only two neighborhoods are changing more rapidly: Hunters Point, Queens and Greenpoint…

Upon reaching the north end of 7th Avenue at Flatbush Avenue, which serves as the divider between Park Slope and Prospect Heights, I noticed this superior row of brick dwellings with stores on the ground floor. The central building, #305 Flatbush, is labeled “Prospect View” on the cornice along with the date of construction, 1889, on the pediment. These are actually the back ends of buildings that front on Prospect Place, around the corner, and were built by developer F. Keith Irving.

Flatbush Avenue at 6th Avenue. As I have said few neighborhoods in NYC are changing more rapidly than downtown Brooklyn. The towers seen in the background here did not exist, for the most part, five years ago. Some, but not all, of the new buildings are part of the Pacific Park development spearheaded by developer Bruce Ratner in the early 2000s formerly known as Atlantic Yards. Several high rise buildings have been constructed, with more expected over a platform covering the Long Island Rail Road trainyard along Atlantic Avenue. The project was fiercely opposed while it was on the drawing board by groups such as Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn. On this FNY page, I listed the structures, some historic, that would be razed so the project could go forward. At length, homeowners and renters in the “line of fire” received substantial payouts and their buildings came down.

Here we go again, as developers want to tear down several blocks around Penn Station for glass office towers, including a 150-year-old Catholic church, St. John the Baptist, seen here on FNY’s 30th Street page.

I have always been fascinated by the “triangle buildings” found in the 3-sided plots formed by Flatbush Avenue as it cuts through the overall east-west grid. In the above photo we see one at the triangle at Flatbush and 6th Avenues and Bergen Street.

The Providence Apartments can be found at the obtuse angle formed by Flatbush and 6th Avenues.

New meets old at #208 Flatbush Avenue as I passed an ancient iron pole that once supported streetcar wire. Across the street, new Pacific Park buildings constructed in the late 2010s are seen. Until 1951, the #41 trolley line plied the avenue; today’s B41 bus matches its route, south to Avenue U with a branch east along Veterans Avenue to Bergen Beach.

The linchpin of Pacific Park is Barclays Center (named for the British bank that agreed to a 20-year naming rights agreement for $200M, opened in 1920 and home to the Brooklyn Nets and temporarily, the New York Islanders. It was developed by SHoP Architects after its initial architect, Frank Gehry, bowed out of the project. Its “preweathered” red steel bands are supposed to evoke Brooklyn’s brownstones; but to me, they look rusty. Barclays is backgrounded by One Hanson, the Williamsburg Bank Tower, which was the tallest building in Brooklyn for nearly 8 decades after it opened in 1928; it has now been surpassed several times.

One of Flatbush Avenue’s “triangles” can be found at Flatbush, 5th Avenue and Dean Street. For nearly a century, from 1912-2012, the wedge-shaped building in the plot has housed a sporting goods store. By the 1960s, when I began riding by in a bus, the store was called Triangle Sports, quite reasonably enough.

Though the plot sold for over $4M in 2012, the building itself has stood empty on the top floors since Triangle Sports moved out. This is, of course, the west end of the vast Pacific Park complex (formerly Atlantic Yards), which was spearheaded by the opening of Barclays Center in 2012. In 2022, a new retail shop was opening on the ground floor.

Until 1940, the 5th Avenue El turned here from Flatbush Avenue; the line originated on the Manhattan end of the Brooklyn Bridge, near City Hall, and its southern terminal was at 3rd Avenue and 65th Street.

When I was a kid, I was in the Cub Scouts. We got my uniform, belts, handbooks etc. from Triangle Sports — but not this one. There was a convenient branch at 5th Avenue and 83rd Street, a block from my house. That particular outlet closed in the 1970s or 1980s.

Brooklyn’s Long Island Rail Road terminal, Atlantic Terminal, opened in January 2010 at the west end of the new Atlantic Terminal shopping center featuring a Brooklyn branch of Target. Having all the charm of George Orwell’s Ministry of Love, it replaced the original terminal building. When the railroad line from Brooklyn to Jamaica was electrified in 1905, the terminal building you see above was constructed. It was no great beauty like its cousin in mid-Manhattan, but it was built with contrasting brickwork, terra cotta highlights, and boasted a cathedral-esque two-story high waiting room. Art Hunecke, whose online LIRR collection Arrts Arrchives is one of the great treasures of the internet, has collected over a dozen photos of the 1907 Flatbush Avenue terminal, making the site its chief legacy.

The Flatbush Avenue terminal died a slow, agonizing death over several years between 1972 and 1988. The waiting room, interior shops and lobby had been closed by the early 1980s, and when you entered the building, you were hustled down to the basement, closed off by a metal partition, where the LIRR ticket office and LIRR tracks, as well as the Atlantic Avenue IRT station, were located. The building itself was pulled down in 1988, leaving a few fleeting bricks on Hanson Place, as well as a gargantuan hole in the ground for the next 15 years or so, before the Atlantic Terminal shops, which included a new LIRR ground lever ticket office, were built from 2000-2004. The corner property was left unfinished until seemingly endless construction on the new Flatbush Avenue terminal began in 2007.

In 1908 Brooklyn, specifically Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues, was considered a remote redoubt indeed as far as the IRT Subway was concerned. It was that year that the original subway, which had expanded uptown into the Bronx via elevated between 1904 and 1908, made its first Brooklyn foray, opening stations between Bowling Green and Atlantic Avenue in 1908 — and it’d be 12 years again until the IRT pushed east and south to New Lots and Flatbush, though the BRT and its successor BMT set about building new lines and converting steam railroads in Brooklyn in the interim years.

In some stations considered worthy of special emphasis, original subway contractor Heins & LaFarge, who were responsible for the original IRT’s Beaux Arts and rococo touches, built freestanding entrance buildings, in railroad parlance called “headhouses.” Some of these, at Bowling Green and 72nd Street, are still standing, as is this one in the triangle at Times Plaza.

In its original scenario, Brooklyn’s 5th Avenue El ran down Flatbush Avenue, but this building stood alongside it. I first encountered it in the 1960s on bus rides with a parent on the B63 bus, which ran down 5th Avenue and Atlantic, winding up on Furman at the waterfront. By then an extra building hosting a hot dog stand had wrapped itself around the building, as seen on this FNY page, but I’ve recently come across older photos that prove it was surrounded with such excrescences as early as the 1920s. The el came down in 1940.

After the wraparound stand was eliminated, though, the station continued to slide into decrepitude. The Beaux Arts Long Island Rail Road station across the street, built in 1907, also deteriorated until by the 1990s the building was demolished entirely and access to the LIRR was via the subway entrances.

Things began to perk up when developer Bruce Ratner’s Atlantic Terminal shopping center, featuring Brooklyn’s first Target, opened in the late 1990s; a new LIRR terminal building followed. Off to the right of the photo, you can see the Underberg kitchen supplies building at Flatbush and Atlantic; after a protracted land-use battle, it toppled by 2010 and was replaced with the rusty-appearing Barclays Center in 2012. The Pacific Park housing project, which no longer has Ratner as its developer, is set to rise over the trainyards in the next decade.

As for the headhouse itself, it was renovated to what we have today, a glorified skylight. The MTA eliminated subway entrances in the building as part of its rebuilding process, rather than subject commuters to the pedal-to-the-metal traffic on the street surrounding streets.

I’ve been thinking about it. Nobody wants Brooklyn to descend into stagnancy, which it seemed to do from the postwar years almost to the 21st Century. The Dodgers moved away and the only new development in downtown Brooklyn was the Fulton Mall and a new mall at Albee Square that opened in the 1970s, itself replaced by the City Point project consisting of three tall residential towers in 2015. There’s an underground food court, whose vendors (which include a Brooklyn version of Katz’s Deli) seemed to rich for my blood when I visited a couple of years ago.

The behemoth at the center is the prosaically-named Brooklyn Tower, a 93-story, 1,073-foot residential tower constructed adjacent to the classic Dime Savings Bank at the west end of DeKalb Avenue.

Though this part of Brooklyn is changing rapidly a zoom shot up Ashland Place from Flatbush Avenue shows parts of the Williamsburg Bak Tower, Brooklyn Academy of Music, and further north, the King of All Buildings. At left, there is a wedge-shaped Apple Store branch that I find architecturally interesting. Having purchased a new machine in 2021 I’m not in the market but next time I’m around here, I may enter and browse around. My IPod from 2000 still works!

Flatbush Avenue didn’t originally continue north of Fulton Street. When the Manhattan Bridge was built in the 19-aughts, Flatbush Avenue Extension was constructed at a time when Dobbin was still the best way to get from here to there, and the architects were foresighted because the FAE gives motorists a convenient way to get from Manhattan to downtown Brooklyn. It’s unusual that the Manhattan Bridge does not connect to any expressway or parkway: Robert Moses’ grand dream was to build a Lower Manhattan Expressway to connect the Manhattan Bridge to the Holland Tunnel. His power had diminished somewhat by the 1960s, and community outrage stopped him in this goal.

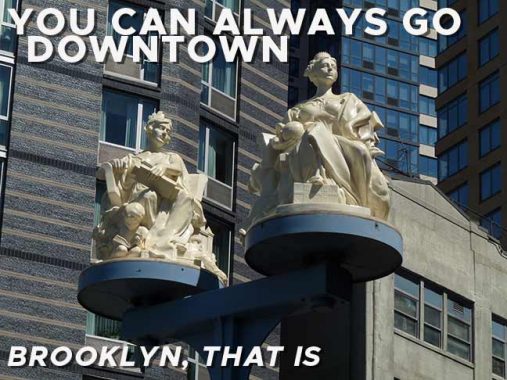

Moses did manage to tear down a pair of statues sculpted by Daniel Chester French called Miss Brooklyn and Miss Manhattan that could be found on the Brooklyn side until Moses had them removed; but in the mid-2010s, revolving replicas built by artist Brian Tolle were constructed of resin and took their place on a pedestal on the FAE median in 2017. Moses, wherever he is, may also be rotating.

Like it or not this is standard issue for modern residential upper middle class housing, at FAE and Tillary Street. However… the hole in the middle is Duffield Street, where you will find a pocket of charming late 19th Century row houses that I was utterly amazed to find on a bike ride many years ago. It’s in a pocket of downtown Brooklyn that is, of course, not designated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

One of Brooklyn’s lest-known and perhaps least-visited WWI memorials is at Bernard Weinberg Triangle, Tillary Street and Flatbush Avenue Extension. This was originally the corner of Tillary and Bridge; as mentioned earlier, Flatbush Avenue would be “extended” when the Manhattan Bridge opened in 1909. The 12-foot tall stele is engraved with the names of over 100 soldiers from the neighborhood who perished in the “Great War.” Six 20-inch tall artillery cases stand to the right of the monument, which is in a windswept and deserted plaza on a cold January day. (The internet is silent on the identity of Bernard Weinberg, so help me out if you can.)

Tillary Street was named for Dr. James Tillary, a colonial-era area physician. In the 1950s it had several extra lanes added when the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway was constructed nearby.

The Cathedral Basilica of St. James, Jay Street between the appropriately-named Chapel Street and Cathedral Place, was built in Neo-Georgian style in 1903, replacing the first cathedral built in 1822. Between 1896 and 1972 it was “demoted” to Pro-Cathedral, as there were grand plans for a bigger brooklyn cathedral, Immaculate Conception Cathedral, but it never worked out and this relatively modest building has been the seat of the Bishop of the Brooklyn Diocese ever since.

Plaques by the front entrance give a short history of the building, and note Pope John Paul II’s visit in October 1979. The “PX” above the door are actually the Greek letters “chi” and “rho”. “Chi” and “rho” are the first two letters in the Greek word Christos or “Christ”.

Beside JPII on the plaque we see his papal coat of arms. Beginning in the medieval era, most popes have had one.

Papal coats of arms feature a gold and silver key. Matthew 16: 18-19: “You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

The Cathedral is about to be dwarfed by a “supertall” residential building that will join so many that have been built during the last five years…

…but one, The Amberly, has already been constructed, at Jay and Concord Streets.

I wrapped up the walk at the York Street IND F train station on Jay Street, which is built well below a ventilation building. For a couple of months when I worked in DUMBO in 2015, I used this station to get there. It’s one of the more difficult stations to enter, as there is just one point of exit/entry and is accessed by a staircase and a steep ramp. As DUMBO becomes a residential area (it was nearly completely manufacturing and warehousing when the station was built in the 1930s) neighbors have pressed for another entry point; but there seem to be no good options for it.

I continue to be fascinated by DUMBO’s transformation. The building on the right, 115 York, was built in 2020 and apartments on the upper floors command exceptional views…if you have the $$$ to pay for them. For me, there’s always MegaMillions.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

12/25/22