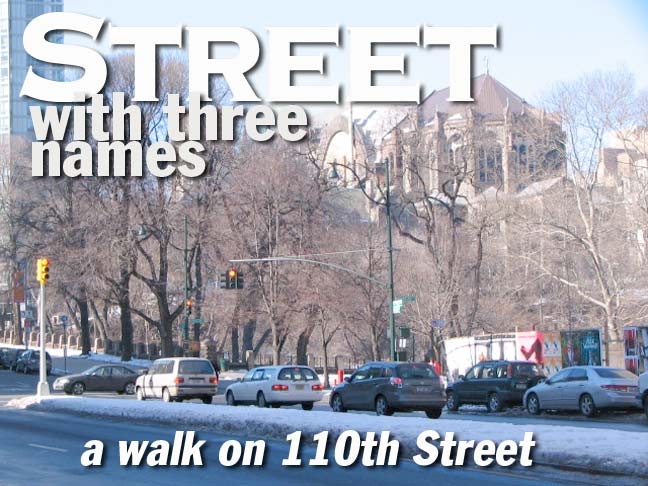

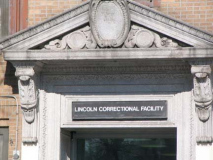

Something a little unusual today: an FNY page composed in 2010 that somehow was left off the two site reconstructions done in 2011 and 2019. Some of this info may be a bit outdated. I was reminded of it because of a news item on May 28, 2023 that the Lincoln Correctional Facility was going to be reopened to house migrants. I have a version saved from my old Adobe GoLive era. Please note, the photos were scanned smaller than I typically do today.

I have done pages on a Little Neck road with three names, and a Brooklyn street with no official name (it was called by a couple of different names before the Department of Transportation settled on Poly Place). Dual-named streets have become more common over the last two decades, as community organizers and politicians have agitated that local luminaries be honored on local street signs; and in the days post- 9/11/01, many names appeared on utility poles as addendums to the main street name, remembering a local who perished that day. I wish the DOT would provide some contest to these names, as in future years, no one will remember the persons listed on the signs.

I’ll even go as far as to say that street names, or at least popular usage of them, can and should be in flux. Vast swaths of NYC contain streets that are named for the last property owner before they sold to the city in the 19th Century and had streets built on them; the names are no longer relevant now. The main reason more names aren’t changed is that it would cost great expense to list them on addresses, directories, etc. In future years, no one will remember the persons listed on the signs.

Today I’ll show you a Manhattan street that has been known for decades by 3 separate names, depending on what part of the street you happen to be on; a fourth was added in 2000! It’s 110th, east and west of 5th Avenue, the street that forms the northern end of Central Park and is the unofficial boundary between the Upper West and East Sides and Morningside Heights and Harlem. Depending on where you are, it’s 110th Street, Tito Puente Way, Central Park North, or Cathedral Parkway.

Beginning at the northeast corner of Central Park, at 5th Avenue and 110th, the cross street is a modest one-lane side street (that nevertheless supports a bus route) running east to just past 1st Avenue. This section is subtitled Tito Puente Way, for the famed salsa percussionist, composer, arranger, and bandleader (1923-2000). He was born in Harlem and lived on East 110th as a youth.

Dominating the traffic circle at 5th and 110th is Robert Graham’s 1997 Duke Ellington Memorial, dedicated to the jazz pianist and bandleader, Edward Kennedy Ellington (1899-1974), one of the most monumental musicians of the 20th Century. It is the first memorial dedicated to an African-American in NYC history.

On July 1, 1997, Robert Graham’s Duke Ellington Memorial was unveiled at the northeast corner of Central Park. Politicians, dignitaries, and Harlem neighborhood residents celebrated the culmination of an effort begun in 1979. Pianist Bobby Short conceived the project, headed fundraising efforts, and coordinated the selection of Robert Graham, a major sculptor of public art, to design the memorial. The result is a bronze tableau 25 feet high, with an eight-foot sculpture of Ellington standing next to a grand piano. Supporting Ellington and the piano are three 10-foot columns, each topped with three nude caryatid female figures representing the muses. The monument itself is inside Duke Ellington Circle. The Circle consists of two semicircular plazas that are stepped to form an amphitheater. Central Park NYC

Before the Ellington and Puente memorials arrived, the traffic circle at 5th and 110th had been called James J. Frawley Circle since 1926, after a Tammany Hall district leader and state senator. Frawley’s construction company built the Manhattan and Queensboro Bridges.

Frawley Circle features a couple of unusual streetlamps with a wrought-iron leaf design. These are the only instances you’ll find them on the east side of Central Park, but they formerly dominated Central Park West from about West 79th south to Columbus Circle. They were all replaced with retro-Twinlamps, positioned parallel to the street, after heavy winds during a 1990s Thanksgiving Parade blew a balloon into one of them, toppling it and severely injuring a paradegoer.

Central Park is entered at Ellington/Frawley Circle via Pioneers’ Gate. As related in FNY’s Secrets of Central Park page, there are 19 gates to the park that were named by the builders in the 1850s, Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. The vista is of Central Park’s 2nd-largest lake, Harlem Meer.

The Meer, an eleven-acre mini-lake, was named after the Dutch word for “small sea.” Like the larger rowboat lake in mid-park, it is an artificial creation, designed and built by Olmsted and vaux to replace a tidal salt marsh and creek that covered the area. Once fed by Montayne’s Rivulet [named for a colonial-era settler, Johannes de Montagne], the same stream used to create the Pool and the Loch, today most of the Meer’s water is piped in from the [Jacqueline Onassis] Reservoir. Its average depth is four feet, but in some spots it reaches close to eight feet. Raymond Carroll, Barnes & Noble Complete Illustrated Map and Guidebook to Central Park

35-story Arthur A. Schomburg Plaza, NE corner 5th Avenue and 110th Street, is an apartment complex constructed in 1975 and visible from most of northern Central Park. Two of the few octagon-shaped buildings in NYC. The complex was recently removed from the Mitchell-Lama middle class housing program.

A prison, overlooking Central Park? 31-33 Central Park North is indeed the Lincoln Correctional Facility, complete with barred windows and ultra-tight security. The building was constructed in 1914 as a branch of the Young Women’s Hebrew Association (YWHA).

The chalet-style building on the north end of Harlem Meer, just south of Central Park North, was built and christened the Charles A. Dana Discovery Center in 1993; it is a park information center, as well as a nature conservatory. It replaced a similar-looking boathouse that had been reduced to a burnt wreck. Fishing is permitted and encouraged form the deck, provided you throw them back in. 50,000 fish live in Harlem Meer: bass, catfish, carp and many others. The Lila Wallace Reader’s Digest Plaza adjoins the building; the Digest was conceived by Lila and DeWitt Wallace in Hell’s Kitchen in 1922. After nearly 90 years of monthly publication, the Digest, deeply in debt, will now publish 10 issues per year.

Two competing residential visions at Lenox Avenue/Malcolm X Boulevard, a gleaming glass tower with balconies overlooking the park, and the Park View Hotel, an erstwhile SRO on the northeast corner that today caters to tourists: The Park View Hotel, at 55 West 110th Street, was once a landing pad for West African immigrants, providing an enduring, if bitter, first impression of New York. Five years ago, there was a term for it: ”Doing the 110.”

The Park View Hotel, at 55 West 110th Street, was once a landing pad for West African immigrants, providing an enduring, if bitter, first impression of New York. Five years ago, there was a term for it: ”Doing the 110.”

While they lived there, these recent arrivals worked as taxi drivers, street vendors and students, trying to climb the rungs of New York’s economic ladder to escape the grimy gray single-room-occupancy hotel, which they shared with a handful of native New Yorkers, many of them welfare recipients.

Fast forward five years: A group of young Swedish tourists linger in the hotel lobby, which is painted in vibrant blues, oranges and yellows and has large leatherette ottomans dispersed around low-lying tables. They plan a day of trips downtown, as clerks at the front desk, wearing matching orange suits, chirpily greet arriving guests from France or England.

The Park View, like much of this block on the northern edge of Central Park, has undergone an enormous transition in recent years. Now a refurbished youth hostel, the hotel, owned by Tenrit Studios, charges visitors $26 to $110 a night for either a shared or private room. New York Times, June 25, 2000

Since the early 2000s, Central Park South has sported a genus of lampposts found nowhere else in NYC; they were placed under the aid of the organization known as the Cityscape Institute, a group devoted to beautifying New York’s sidewalks and street furniture. This design harks back to mid-20th Century designs, with pendant luminaires that seem to be an update of the classic Westinghouse AK-10 “cuplight.”

To me, they resemble DEVO’s famed plastic flowerpot lids (Jerry Casale models one below right). You remember them from “Whip It.” photo: San Diego Shooter

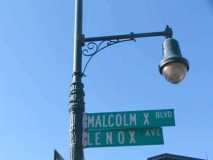

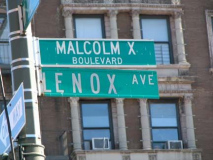

Malcolm X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue) has had three names in its history, since the avenue was originally 6th Avenue before it was renamed for James Lenox, a founder of the New York Public Library, in 1887; 100 years later, it was again renamed, this time for civil rights leader Malcolm X. I may be the only person who has remarked that all three of the avenue’s names have had an “x” in them. In the 1990s, when Lenox/Malcolm X was tricked out with a new set of retro-Corvington longarmed lampposts, it also received a set of “mini-me” Corvingtons that light its relatively wide sidewalks. The “mini-me’s” are also mounted on some regulation-size posts.

Central Park gives rise to not one but two major northern Manhattan routes here, as St. Nicholas Avenue, named for Holland’s patron saint and the progenitor of Santa Claus, the secular symbol of Christmas, strikes off to the northwest; it will zig and zag in a general northwest route all the way to Fort George Hill. The avenue was named in 1866 and follows the path of several older roads of the colonial era, including Harlem Lane and Kingsbridge Road.

A stone and brick apartment building on Central Park North between Lenox/Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell Blvd. was named the Semiramis, after a legendary Queen of Assyria. Semiramis was the wife of Biblical Nimrod of Assyria/ Sumeria, and was astoundingly beautiful. She always wore around her neck a silver charm in the shape of a very arrow-like dove, given to her by her first husband, and men were driven to madness by the sight of her beauty. She was discovered by shepherds after being raised by the doves, and the King’s advisor, Menos, passing through for inspections, noticed her charms and took her and married her. In some versions, they have twins, Hyapate and Hydaspe.

In winter, from Warrior’s Gate at Central Park North and Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard (formerly 7th Avenue) a stone building can be seen atop an escarpment. This part of the park is known as the Cliff and is one of the natural aspects that the Park’s creators, Olmsted and Vaux, allowed to remain while building the park in the 1850s.

From the ForgottenBook:

A chain of major batteries was installed in upper Manhattan during the early days of the War of 1812: Fort Clinton, Fort Fish, a battery at McGown’s Pass, Nutter’s Battery, and Blockhouse Number One were in what would later become Central Park. When it was built, this Blockhouse had a sunken roof with a large cannon that could be fired in any direction. The five fortifications in what would become Central Park had over 2000 militiamen garrisoned.

None of the batteries, fortunately, ever saw combat. The Treaty of Ghent ending the war was signed on Christmas Eve 1814, and the forts were abandoned almost overnight. (Andrew Jackson defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans on January 1815 before word of the treaty had reached the two opposing forces.)

For many years, the Blockhouse was in ruins, and a plaque commemorating its history was stolen. In the 1990s, the Blockhouse was stabilized and its flagpole repainted.

A pair of stolid apartment buildings are the sentinels at Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard and Central Park North.

I believe Cityscape is responsible for the unique Central Park North street signs (which remind me of the Philadelphia street sign design). The Department of Transportation, not to be upstaged, has its own NYC-style sign on the post as well.

At Frederick Douglass Circle, where Central Park West meets Central Park North, a central plaza was under construction that [now features] a statue of Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), the Civil-War era abolitionist, editor, author and orator. 8th Avenue takes his name from here north to the Harlem River. Incredibly, this plaza has been under construction since 2004! Towers On The Park, a condo complex finished in 1988, dominates the NW end of the circle.

According to the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, the plaza [features] a complex colored paving pattern that alludes to traditional African American quilt designs. Harlem-based artist Algernon Miller designed the paving. Additional features, including wrought-iron symbolic and decorative elements, a water wall, and inscribed historical details and quotations representing the life of Frederick Douglass and the slaves’ passage to freedom. A central bronze sculpture, depicting a standing Frederick Douglass, has been crafted by Hungarian-born artist Gabriel Koren. wikipedia

“No man can put a chain about the ankle of his fellow man without at last finding the other end fastened about his own neck.”– Douglass, from an Address at a Civil Rights meeting, 1883

Beginning at Frederick Douglass Circle, Central Park North becomes Cathedral Parkway, although the Department of Transportation offically recognizes it as West 110th Street.

The name recognizes the giant Cathedral of St. John The Divine, which I’ll touch on presently. The city widened West 110th in 1891-1892 to provide a grand boulevard between Central Park and the cathedral at Amsterdam Avenue. So, the cathedral and the parkway have been hand in glove since construction of the Cathedral first started. Subway mosaics on the 1904 Broadway IRT demonstrate this.

The Mountcliff Arch is the northernmost of Central Park’s great arches and bridges that were listed on FNY’s Central Park Arches pages. Built in 1890, it’s among the youngest of these arches.

Morningside Drive and Morningside Park are named because morning light first hits the eastern side of a rocky hill that forms the ridge along which Morningside Park runs between West 110th and West 123rd.

Though Andrew Haswell Green first proposed a park here in the 1860s, citing the difficulties involved in leveling or minimizing the steep hill to cut streets through. A number of plans and proposals were presented but it wasn’t till 1887 that the plan by Olmsted and Vaux, the Central Park architects, was put in play.

Fourteen years after their original proposal was rejected, landscape architects Olmsted and Vaux were hired in 1887 to continue improvements to Morningside Park. They enhanced the park’s natural elements by planting vegetation tolerant of the dry, rocky environment. Two paths– one broad, one meandering — traversed the lower portion of the park. Retained as a consultant, Vaux saw the work to completion in 1895, the year he drowned in Gravesend Bay. Parks Superintendent Samuel Parsons Jr. wrote of Vaux’s work, “. . .perhaps Morningside Park was the most consummate piece of art that he had ever created.” NYC Parks

The massive Cathedral of St. John The Divine, which has been under construction since 1891, is hardly Forgotten, but any survey of West 110th/Cathedral Parkway is incomplete without mentioning it. It was begun on the former site of the Leake and Watts Orphan Asylum, whose 1843 building still remains on campus. Episcopal Bishop Henry Codman Potter commissioned architects Heins and LaFarge (who would subsequently design the NYC Subway system’s earliest stations). By 1911, with the church still under construction, Ralph Adams Cram took over as architect, but by 1942 only the great nave and west front had been completed.

America’s entry into World War II halted construction, and the Cathedral did not have much more work done until 1979, when work resumed under Bishop Paul Moore, Jr., and stonemason James Banbridge. A devastating fire in December 2001 meant a setback, but the damage has now been repaired. When finished it will be the world’s largest cathedral (amazingly, the Roman Catholic St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome is not officially a cathedral!) The massive cathedral is large enough, and old enough, to contain works by both Rafael Guastavino and Keith Haring; it contains the Rose Window, the largest stained-glass window in the world.

To some, Greg Wyatt’s Peace Fountain, in a plaza just south of the Cathedral’s flying buttresses on Amsterdam and West 110th, is mysteriously devotional, but to your webmaster, its crab claws, gamboling giraffes and severed Satanic heads are just plain bizarre.

The fountain depicts the Archangel Michael triumphant bestride the defeated Devil. Giraffes, in Wyatt’s iconography representing peace, gambol on stylized moon and sun figures, while a giant crab rests on a DNA double-helix-shaped pedestal. Surrounding the fountain, you will find bronze animal sculptures constructed by New York City schoolchildren. The Fountain was unveiled in 1985.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

3/20/10, revised 5/28/23

1 comment

The subway station platform walls at W 110th Street, both the IND at Central Park West/Frederick Douglass Blvd., and the IRT at Broadway, have large mosaic panels featuring “Cathedral Parkway.” That street moniker goes all the way west to Riverside Drive, creating a continuous “parkway” between Central Park and Riverside Park. Interestingly at its far west end, Cathedral Parkway jogs sharply to the northwest and intersects Riverside Drive at West 111th Street.