By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

In July 2023, Kevin rediscovered a lost street in downtown Manhattan named Cheseborough Court, which ran for a block between Bridge and Pearl Streets, near Battery Park. But a short hop to its north there was another ephemeral street piercing the city’s most important historic block, Whitney Street.

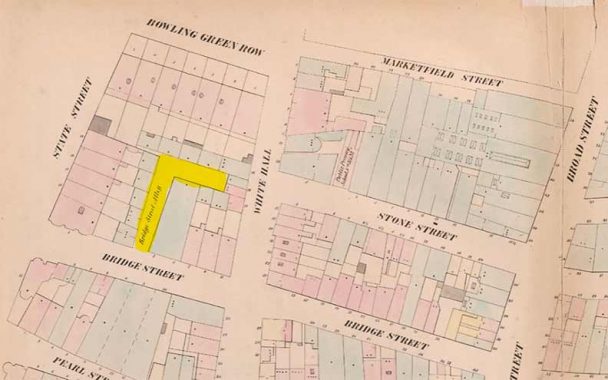

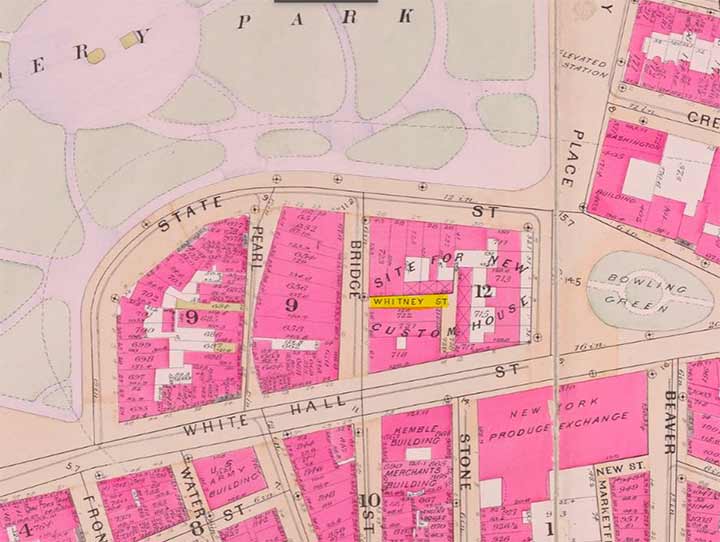

In the 1893 Robinson & Pidgeon excerpt shown above, we see it among the rowhouses marked as “site for new Custom House.” The buildings were condemned and in 1901 construction began on the beaux arts structure, wiping out this dead-end street.

|

|

|

The earliest appearance of this street on a map was in the 1852 William Perris atlas where it is named Bridge Street Alley. It has no addresses on it, serving as a driveway to stables behind the rowhouses. Between 1852 and 1893, most maps did not label this little street. There are many famous Whitneys in American history so the namesake here is unclear. Perhaps dry-goods merchant Asa Whitney or cotton-gin inventor Eli Whitney. Their earliest ancestor in America was Puritan settler John Whitney who arrived in the Plymouth colony in 1635.

On the site of Whitney Street is a truck loading bay for the Customs House, so in a way, vehicles can drive on Whitney Street without knowing it. The block on which the Customs House stands has a long history. I did not wish to photograph this driveway from up close for security reasons.

I could not find any photos of this obscure street, but an aerial photo from 1896 shows the rowhouses that stood around it. The tracks seen here connected to the Sixth and Ninth Avenue elevated lines. With the expansion of the subway system, they were removed by 1940.

Another photo from that time period shows the condemned rowhouses at the corner of State and Bridge Streets, near our forgotten dead-end.

In 1790 it hosted Government House, which would have been the presidential mansion but that year Congress moved the federal capital to Philadelphia and then to Washington, D.C. It then served as the governor’s mansion before the state capital was relocated to Albany in 1797. The building was demolished in 1815 and replaced with a set of rowhouses. This view shows Government House in 1795 from Battery Park. The entrance stairs faced Bowling Green and the site of Whitney Street was behind this building.

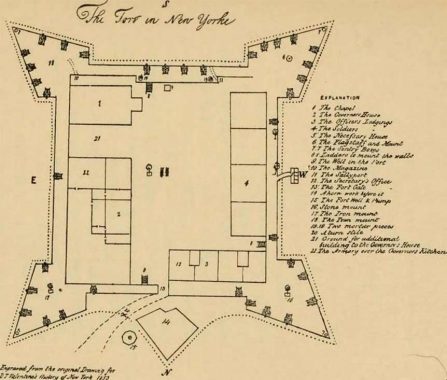

Before Government House, this block was the citadel of New York, a military and political center established by the Dutch as Fort Amsterdam. Diagrams, maps, and models of the fort allow us to reconstruct this early seat of power. After the English arrived in 1664 it was renamed Fort James and then as Fort George in honor of the ruling kings.

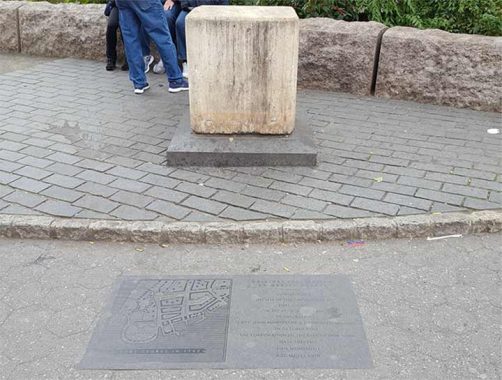

A marble block installed in 1818 is among the early examples of city leaders recognizing a building that should have been preserved. It was installed 28 years after the demolition of Fort George. Long before the Landmarks law came to be, there were historians and prominent citizens who recognized the value of Fort Amsterdam to the city’s identity, but business interests prevailed as they do throughout the city’s history.

Quebec has its old city walls, Moscow has its Kremlin, and Jerusalem has the Tower of David. But New York’s old citadel today is merely a block on the map.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

8/9/23

7 comments

“The Fort in New Yorke”?Is that an “e” at the end York,or is that just a little flourish

at the end?

what a find! thanks for the post.

to Chris…New-Yorke (with and without the hyphen) was one of MANY completely valid historical renderings of the name

The hyphen is still in use as the name of the New-York Historical Society, but they chose not to use the “e.”

I’m guessing that since there were no drones in 1896, that aerial hot was from a hot-air balloon? Amazing they could keep it stationary and get an exposure sufficiently clear to print.

In 1896 there was a taller building a block to the east of Whitney Street, which made that view possible.

The 1896 photograph of the block was most likely taken from the Produce Exchange building across Whitehall Street rather than from a balloon.

A staffer at the Manhattan Borough President’s Topographical Bureau solved the mystery here. Whitney Street’s namesake is property owner Stephen Whitney.

In 1818 he petitioned the city to “improve” his property on this block.