In contrast to the Upper West Side, which has a continuous waterfront park on the Hudson River stretching from 59th to 125th Streets, the shoreline of the Upper East Side has an industrial past that prevented a similar park on the East River. As the industries gave way to hospitals and apartments, a few parcels, such as the space between E. 76th and E. 78th Streets, were designated as parks.

Title image: Manhattan Sideways

On the southbound FDR Drive is an old building hemmed in by its neighbors, bearing the inscriptions “East Side House Settlement” and “1891-1903.” Located in the middle of the block between 75th and 76th Streets on the Upper East Side, it does not have an entrance onto the highway and the present-day East Side House Settlement is located further uptown in the Bronx. This hidden building was a catalyst for public facilities in this neighborhood, leading to the founding of the nearby library, school, and John Jay Park.

As we’ve documented the city’s superlatives over the years, the FDR Drive sidewalk on this block is perhaps the narrowest in the city that is open to the public. As noted in my essay on the unrealized park that was Jones Wood, this waterfront road was designated by Mayor LaGuardia in 1935 as Marie Curie Avenue, but the name was quickly forgotten when this road opened in 1940 as East River Drive. It was renamed for President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945 shortly after his death. Thirty years later, the island facing this road was also renamed in his honor.

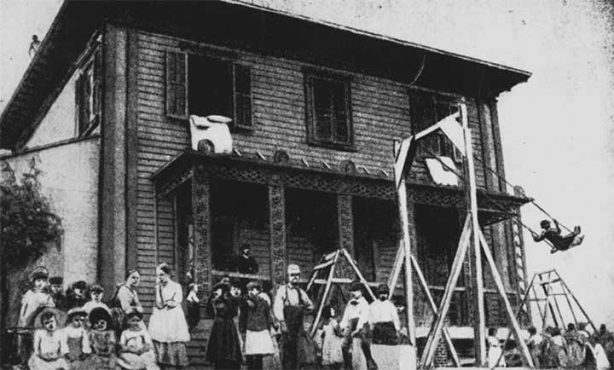

When the East Side House Settlement opened in 1893, it occupied an old clapboard house on a bluff overlooking the East River. At the time, the shoreline here was industrial, with a power plant, coal docks, and cigar factory as its neighbors. The workers in these establishments were mainly immigrants from Germany, Czechia (Czech Republic), and Hungary, whose churches still stand on nearby blocks. The nonprofit was part of the larger settlement house movement that provided services to New York’s poor and immigrant families.

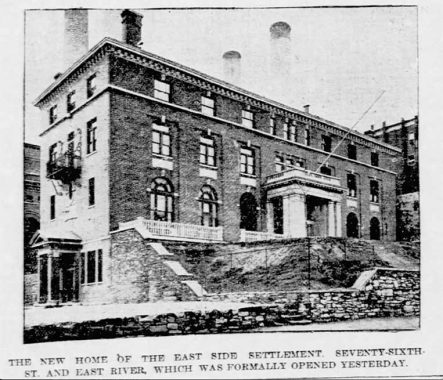

As its clientele grew, the settlement house’s philanthropists funded a bigger structure that was completed in 1911, which explains the inscriptions on its wall. The New York Tribune reported on its grand opening, and its photo shows an entrance on present-day FDR Drive below the iron balcony. The main entrance faced E. 76th Street. Ephemeral New York offers more details on this building. A year later, the city constructed Cherokee Place and John Jay Park on the block north of the settlement house. The landmarked Cherokee Apartments were documented on Kevin’s visit to this block in 2011.

The Forgotten-NY element here is the eastern tip of E. 76th Street. As the neighborhood became more affluent and less industrial, East Side Settlement House decided in 1963 to move uptown to serve the residents of Mott Haven. The building was then purchased by The Town School, an expensive private school with its own proud history in the neighborhood. In the 1970s, this school expanded and the old settlement house was connected to an expansion wing facing E. 76th Street.

On this dead end, the street is covered in paving blocks reminiscent of a driveway, but this is a public street. We’ve documented Belgian blocks, red brick, and yellow brick streets in this city, and this block offers the only example of octagonal square pavers.

Further inland on this street is another private school, Lycée Français de New York which offers a bilingual education focusing on French culture. Its present building on this block opened in 2003. The names on the walls represent the leading thinkers of French and American societies.

As Kevin noted last year, Cherokee Place runs for one block, but it used to have two. The section between 76th and 77th Streets was demapped in 1942 and annexed to John Jay Park. The landscape architecture firm Thomas Balsley Associates laid out the bricks here to accommodate the Douglas Abdell sculptures (see below).

Initially placed on a Park Avenue median in 1977, it was later moved here by the city. Eaphae-Aekyad #2 represents a letter sculpture from an imagined language. “Although Abdell’s sculptures appear physically minimal, the reality is that they are full of figurative and complex ideas. Figurative art is a representation, and in this case, the Aekyad sculptures represent Abdell’s attitude towards languages and his studies of geometry,” designer Legare Sinkler wrote in her critique of his works.

If non-objective sculpture doesn’t interest Kevin, behind Kryeti-Aekyad #2 is a unique lamppost that he would appreciate. The shaft is a standard NYC Parks design but the beacon is unique to John Jay Park. Kevin knows the taxonomy of every lamppost species in the city. The pedestrianizing of this block of Cherokee Place predates the sculpture by two decades, as seen on this map from 1955.

I haven’t seen this combo before. It’s a Flushing Meadow fixture plopped on a Type B park lamp. –Ed.

The city’s aerial survey from 1924 shows John Jay Park and its neighbors. It had the Gothic Revival field house and separate playing fields for boys and girls. The park’s swimming pool was completed in 1940 as a federal works project in tandem with FDR Drive. The park hasn’t changed much since then, although there was a proposal in 1966 by Paul Rudolph to install a slew of concrete ramps in the park. It looked nice on paper but this is no place for Brutalism.

In a neighborhood of astronomically expensive apartments, some of which have private indoor and rooftop pools, commoners can use this free pool in the park. Tucked away on a dead-end by the river, it is never crowded and was a favorite of the late Parks Commissioner Henry J. Stern. Swimming here feels like having a membership in an urban country club, but all you need are a bathing suit and towel.

Across the now-pedestrianized Cherokee Place from the park there was another bathhouse, designed in 1905 by the firm Stoughton & Stoughton in the beaux arts style. At the time, many of the city’s tenements did not have showers, so these public baths were built as a public health policy.

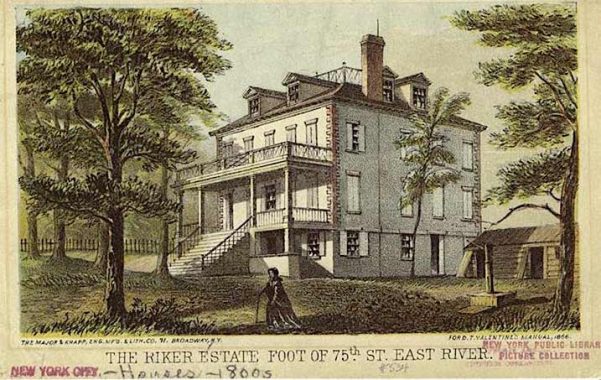

The completion of John Jay Park’s pool across the street made this bathhouse redundant. In its place, The Pavilion, a massive apartment building with its own zip code was built in 1962. Curiously, its name honors the Riker family’s colonial estate on this site.

The mural behind the lobby’s concierge desk depicts the old mansion, which was demolished in 1899. Its appearance resembles Gracie Mansion, 15 blocks to the north. The Rikers had relatives in Queens, whose house was documented by Kevin in 2006, and an island in the East River that later became the site of the city’s jail.

The park’s namesake was a Founding Father who served in the Continental Congress, then as a diplomat, first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and as this state’s second governor. His name appears on a high school in Park Slope, Fort Jay on Governors Island, John Jay Hall at Columbia University, and John Jay College of Criminal Justice. His estate in Rye and his homestead in Katonah became state parks.

East 78th Street has a footbridge connecting to the East River Esplanade, a walkway on the water’s edge running between the East River Greenway and Carl Schurz Park. The smokestack seen here is the former IRT Powerhouse that served the elevated trains on Second and Third Avenues. After their removal, it became a Con Ed power plant. The Museum of the City of New York has a photo collection of the plant under construction in 1912. It also appeared in a painting by Jara Henry Valenta in 1934.

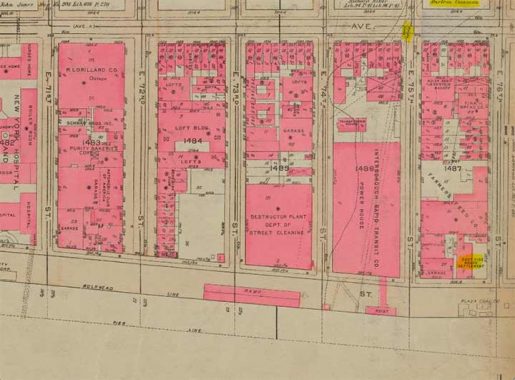

The site of the power plant has a place on old property maps as the southernmost point of the border drawn in 1658 separating New Amsterdam and New Harlem. The line ran diagonally across the island to the Harlem Cove on the Hudson River at W. 129th Street. After England annexed New Netherlands, the two towns were united as New York, representing the entirety of Manhattan island. Here, the line appears on a G. W. Bromley property survey from 1930.

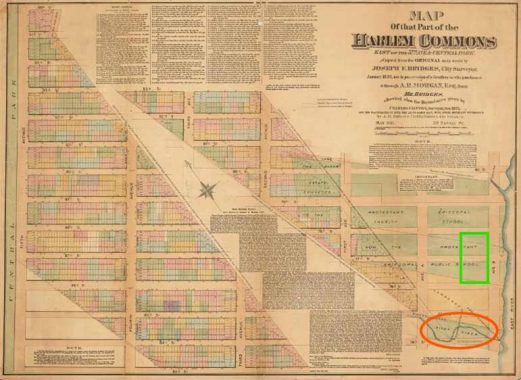

Why was the southern tip of Harlem placed here? Because at E. 74th Street, near the mouth of the long-forgotten Saw Kill was its eponymous saw mill. This map from 1836 shows the border as it relates to property owners. I circled the site of the power plant and marked the site of John Jay Park.

Looking inland on E. 74th Street, where Saw Kill flowed into the East River, a recently-built tower of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center expands the medical district on the waterfront that begins at E. 60th Street, with the power plant here as the neighborhood’s last industrial structure. Prior to its completion in 2020, the site of this 25-story barcode-striped tower had a trash incinerator plant. During the Dutch period, African slaves worked at this location, cutting down trees and transporting the lumber downtown for shipbuilding. Their camp is marked by the letter F on this map from 1639. The Brooklyn-based Saw Kill Lumber Company adopted its name in honor of this history, which it offers on its website.

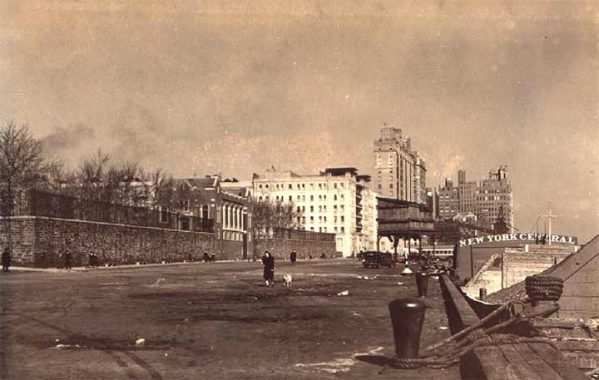

Between 1933 and 1940 city photographers Percy Loomis Sperr and George J. Balgue documented the transformation of the shoreline next to the park from coal barge docks to a boulevard and walkway. Considering how FDR Drive is hidden below Carl Schurz Park, Rockefeller University, and the United Nations, perhaps it’s a matter of time before John Jay Park is expanded with a deck above this highway.

On my return home from John Jay Park, I couldn’t resist taking one photo of the landmarked Cherokee Apartments, a hidden detail of its Guastavino tiles and sculptural ironwork under each balcony. Although they are not as decorated, across E. 78th Street is another set of landmarked apartments, City and Suburban Homes, completed in 1913 as a low-income development.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop. As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

7/26/25

4 comments

Let’s see … extremely narrow sidewalk, speeding cars a few feet away, separated only by a flimsy guardrail.

Nothing could possibly go wrong with that, right?

Good.Because KW rarely goes above 59th st.

A guy built a shelter on that narrow divider on the FDR drive once.

How he got to and from it without getting run over is unimaginable.

Plus he must have been deaf because the noise would be horrendous.

And thats where he died too.I dont know how long his body stayed

there before anyone noticed.

Very interesting article Sergey. I lived around the corner on 75th Street for years and everything you wrote about fascinating. I do have a slight correction however. While the East Side Settlement House might have been a catalyst for John Jay Park, there was an earlier, more important catalyst for it (and Rainey Park, directly across the river in Astoria). In 1867, the city bought land on both sides of the East River for the bridge piers of a bridge that was to go from the Upper East Side to Astoria. The city had a hard time pulling financing together (the Financial Panic of the 1870s) for the project so work on the bridge did not start, under the guidance of Dr. Thomas Rainey, till 1881 with the sinking of a caisson in what is now Ravenswood’s Rainey Park. Then the money ran out. The city on the land for years until it was obvious no bridge would be built there. That land became John Jay Park in Manhattan and Rainey Park in Ravenswood / Astoria. I do not know, but maybe the Settlement House was built on city land.

Old maps and surveys, such as the 1930 Bromley survey open a wonderful window into the past. Look at the names and uses of the buildings that are shown. You mention that the site of the recently new MSK tower had been a “trash incinerator plant”. The 1930 Bromley has the site identified as “Deconstruction Plant Dept of Street Cleaning”. What was “deconstruction”? When did the “Dept of Street Cleaning” morph into the Department of Sanitation? The block north of the IRT (now ConEd) power plant has a large group of buildings and open yard identified as the “Farmers Feed Company”. In 1930 the only remaining working farm in Manhattan was on the northeast corner of Broadway and 213th Street, but it didn’t have working animals that required feed. Most likely, it provided feed for the rapidly shrinking horse population that was being replaced by motorized trucks. It is also likely that, with the declining need for its product and the onset of the Great Depression, that it didn’t survive too much after they were documented in the survey. A few posts about tje lost industries and public service buildings that can be found as “ghosts” on old maps might be interesting.