I enjoy a stroll around Fort Totten, located in eastern Queens at the north end of Bell Boulevard where the Cross Island Parkway turns west. From 2017-2021 I often bicycled the bicycle path alongside the CIP and into the fort. These days, I need to settle for a bus ride. I am attending PT for a problematic back and still fear lifting my leg high to get on a bicycle and quickly moving my legs, though I can handle the stationary bike at PT easily enough. Maybe sometime soon I can resume bicycling without fear of spasming my back, we’ll see.

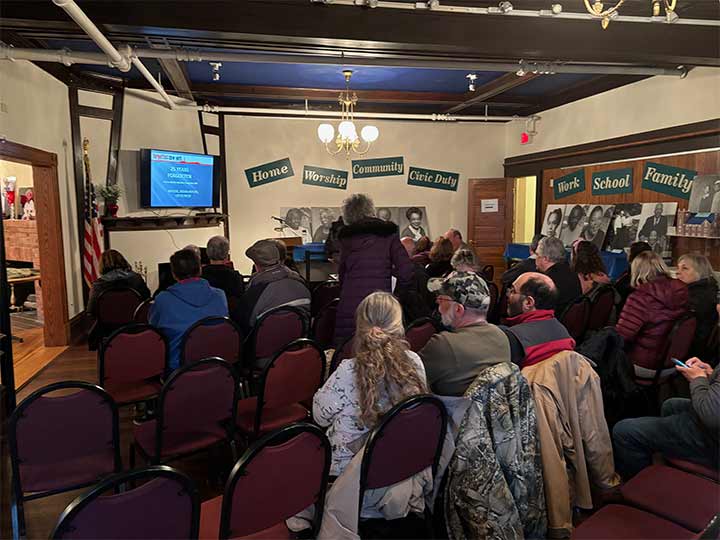

Pictured is one of the “sold-out” (they were free) in person talks I gave during Forgotten NY’s 25th anniversary in 2024, in which I gave Powerpoint shows around town. I still do them on zoom, but can appear on request provided you have sound and video systems. Let me know at kevinjudewalsh@gmail.com. Incidentally, the empty seats in the photo were soon filled after the photo was taken. It was held at the Fort Totten Officer’s Club, also the home of the Bayside Historical Society, in April 2024.

Though the MTA labels the Shea Stadium station on the #7 Flushing Line as being at Willets Point, the actual “point” is miles away, on a little spit of land jutting into Little Neck Bay just east of the Throg(g)s Neck Bridge. (The station name refers to Willets Point Boulevard, whose Flushing section runs under the stop.) Since 1870, Fort Totten has guarded the harbor at Willets Point, along with its older sibling, Fort Schuyler in Throgs Neck, Bronx.

The government first contemplated adding fortifications at Willets in 1856, from a belief that there were greater fortifications necessary to protect NYC from an enemy fleet in the Atlantic Ocean. The proposal was discussed in detail in an article by Brigadier General Joseph Totten in a Flushing Journal article that year. The completed fort was renamed (from Camp Morgan) for the general in 1896.

On May 16, 1857 land comprising 100 acres was acquired from the Willet family by the government, and six years later, additional acreage was purchased from Henry Day. Additional adjoining marsh and swampland was filled in that completed the territory that would comprise the future fort, which brought the total acreage to 163 acres. Named Camp Morgan, it was used to train Civil War recruits.

Fort Totten’s military operations ended in 1967. After that, it became a mostly unarmed residence for military families. The Coast Guard took over 10 acres of the base from the Army in 1976. Since the late 1960s a number of organizations — mostly non-profit or government agencies — have leased space within unused fort buildings. The NYC Fire Department uses part of it as a training facility. Aside from that, much of Fort Totten has been always-welcome parkland for over a decade.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop. As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

9/4/25

7 comments

Just a minor comment, Kevin. The MTA stopped using “Shea Stadium” once CitiField opened in 2009 . At that time they officially called the subway station “Mets-Willets Point”. They also used the new name for the LIRR station. A couple of “Shea Stadium” signs on the southbound platform did stay in place for a couple of years until they were finally removed.

The reason the station is not called “Citi Field” is that, unlike Barclays, Citi was unwilling to pony up the mazuma to buy the name of he station. One wonders if Etihad, the naming sponsor of the NYCFC stadium being built next door, will be willing to pay for the privilege once that facility is completed.

CitiCorp is paying $20 million a year for the remainder of a 20 year agreement (it expires within a few years and can extended for another 20). You would think they could put up a little bit more for naming rights on the subway station.

General Totten was a well-regraded engineer. He invented what were named “Totten Shutters”, which solved a major problem for fortress gunners. The openings through which a fort’s cannon were fired allowed enemy fire to come into the fort and endanger the gunners. Totten invented shutters that would cover the openings, but swing open immediately prior to a projectile exiting the gun and closing immediately afterwards. The design was simple, but effective, and saved countless lives.

“Saved countless lives”?

Please give some examples. I’ve never heard of this. By their very nature, forts and embrasures protected gunners enough. The shutters would help, but did they really save “countless lives”? What battles and sieges were they used in?

If the enemy could have such pinpoint accuracy as to lob shells into the narrow openings for the guns, then they could easily hit the shutters too, putting them out of commission and thus putting the fortress gun out of commission, unless they have mechanics who can easily remove or repair the damaged shutters. Or, potentially suicidally, they would try to fire out through the closed, damaged shutter. These shutters sound like a terrible idea.

The Totten Shutters were a physical part of a fortress, protecting the gun embrasures and the crews working behind them. Following are two links that will explain how they worked. In the years following the Civil War, masonry forts rapidly became ineffective due to the improved guns and projectiles from naval vessels. In fact, Fort Totten, in Bayside, was never completed, as there would have been no value in doing so.

The first link is from the NPS regarding the history of Totten Shutters and the restoration of them at Fort Jefferson – Dry Tortugas in Florida.

https://npshistory.com/publications/drto/brochures/totten-shutters-2014.pdf

The second link is a video at Fort Delaware State Park, in Delaware, which explains how open embrasures were a long-time problem for gun crews and how the Totten Shutters worked to protect them.

https://www.facebook.com/FortDelaware/videos/totten-shutters/5557788217643403/