Most people who have commuted into New York City from New Jersey or Long Island, or perhaps taken the train from other parts of the country like Washington, Boston, or Chicago in the past 35 years, have thought of Penn Station as the basement under the Felt Forum on 33rd Street. A large basement, with shops, newsstands and ticket booths, but still a basement.

Between 1910 and 1964, though, a great monument to travel existed on this site. The largest building ever erected for rail travel, Pennsylvania Station, commissioned by Pennsylvania Railroad President Alexander Cassatt and built by architectural firm McKim, Mead and White, stood between 31st and 33rd Streets and 7th and 8th Avenues — over eight acres. It was truly a temple of transportation.

With the 277-foot long waiting room designed to resemble the Roman Baths of Caracalla and the Basilica of Constantine, the grand edifice used 500,000 cubic feet of granite; was supported on 650 steel columns; required the digging of tunnels over 6600 feet long under the Hudson River; required the demolition of over 500 buildings and the removal of over 3,000,000 cubic yards of soil and bedrock. It had a 150-foot ceiling.

Pennsylvania Station in about 1925.

This is the concourse of Pennsylvania Station soon after it opened in 1910. You could stand on the concourse and watch the trains enter and leave the station, as sunlight streamed through the skylights.

Later, when the overhead catenary wires were installed, replacing third rail in the station, the floor was extended and the view to the tracks was obscured.

Everything has now been torn down except for a few of the brass bannisters on the staircases. Note the ornate track indicators, two for each track at either side of the staircases.

The vagaries of transportation took their toll on the station over the years after WWII, and both the Pennsylvania Railroad and its grand station began their decline. Concessions to the modern age like neon signs and illuminated advertising, as well as deferred maintenance which left a thin layer of dirt over what were once magnificent pink marble columns, left Penn Station, which was only a half century old in 1960, looking a lot older than its actual age. People were moving to the suburbs and deserting the cities. The automobile and the jet airplane had superseded the railroad as the preferred method of travel in the United States. To compound the trouble, Penn Station had never developed the symbiotic relationship with its neighborhood on the West Side the way that Grand Central Terminal had over on the east side.

And so it was decided as early as 1955, when the “Pennsy” sold its air rights above the Station, that Penn Station must eventually be torn down. Though the building was meant to last for centuries, it lasted 53 years.

You know what, though. If you poke around long enough in the basement of the Felt Forum, which is what the ‘new’ Penn Station became, you can find a hint or two of the old magnificent Penn still there. And you can even find a couple hints in broad daylight too.

Penn’s eagles

This is one of 22 nearly three-ton eagles that appeared on Penn Station’s exterior.

Lorraine B. Diehl, in her comprehensive history of Penn Station, The Late Great Pennsylvania Station:, writes:

...the first of the six stone eagles that guarded the entrance was coaxed from its aerie and lowered to the ground. The captive bird was surrounded by a group of officials wearing hard hats. They clustered about their trophy and smiled for photographers. Once the servants of the sun, symbols of immortality, the stone birds that had perched atop the station now squatted on a city street, penned in by sawhorses as their station came down around them.

In all there were twenty-two eagles crowning the station, each weighing fifty-seven hundred pounds, each given its form by the noted sculptor Adolph A. Weinman…

Two of the stone eagles were rescued and placed outside the new entrance.

This Penn Station eagle has found its way to the courtyard of a building on 3rd Avenue near St. Marks Place.

2012: the building has since been demolished, but I hear that the eagle will be going ion the new building’s roof.

The Philadelphia eagles. 4 of the Penn Station eagles have made their way to each end of the Market Street bridge over the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, PA. photos: Rochelle Rabin

Two more, meanwhile, flank the entrance to the main building at the US Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, Long Island. WAYFARER MAP LOCATION

Here’s a definitive look at where the various eagles wound up.

Some of the staircases (like Track 17, here) still have the original brass banisters and “X” shaped molding. See above picture of Penn Station in 1910 for these staircases in their original incarnation.

A small area of the original Penn Station can be found when you walk toward the front of the downtown IRT local platform. This ledge, containing original brass bannisters and tiled arches (with the addition of modern lighting) is at the top of the staircase leading down to the token booth. Through soaped up windows can be glimpsed more arches in an area used for storage.

When Penn Station was originally constructed in 1910, the automobile was in its infancy and you were just as likely to arrive in a carriage as you were in a car.

Penn Station had two carriageways, the north for the Long Island Railroad passengers and the south for the Pennsy.

What you see here is the brick floor of one of the carriageways. It is in what is now used as a service entrance. Above, in the ceiling, can be seen a small piece of the pedestrian walkway that arched over it.

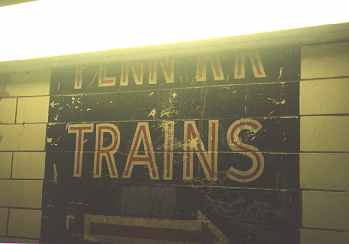

A hand lettered sign can still be seen above the arch leading to the subway platform on the downtown IRT platform.

In its glory days the floor of Penn Station was laid with thousands of glass bricks like the ones at left, which were still in a baggage area near Track 1 (by 2012, long replaced).

The Kansas City, MO Eagle Scout Memorial employs Penn Station’s exterior clock sculptures. Here’s the story on how they wound up there.

Possibly the most intriguing find is the discovery of part of an original track indicator in the baggage area near Track 1.

Lorraine Diehl:

With acute attention to detail, the train indicators, placed at the boarding gates, had been specially designed to conform to the ornate fencing that enclosed the platform area. Each indicator stood sixteen feet high and was of cast-iron painted black. The aluminum sign cards, which displayed the name of the train as well as its stops, were painted bright red, the only touch of color in this room of black and grey.

This track indicator has been compromised since its heyday. It only has one face (others had four). The track number appeared in the semicircular area on top. The two numbers on the bottom were used in the departure time.

The Pennsylvania Railroad merged with New York Central to become Penn Central in 1968; the whole shabang went bankrupt in 1970. Probably the only extant remnant of the Pennsylvania Railroad — besides the name Pennsylvania Station, of course — is this painted sign that can be seen in the passenger concourse behind the Long Island Rail Road station. It escaped renovation along with the rest of the LIRR station in 1992.

Sources:

Lorraine B. Diehl, The Late, Great Pennsylvania Station, Four Walls Eight Windows 1996

Ron Ziel, Steel Rails To The Sunrise, Hawthorn 1965

11/5/1999; revised 2008, 2012

5 comments

When I first learned of the original Penn Station, not only was I saddened to know of its demise, but to find a familial connection made it even more touching. My father was a construction worker in the 50s to the early 1970s, when he died at the early age of 43. In the 1960s, when I was in my first decade of life, my dad was one of the construction workers at the new Felt Forum/ Penn Station building. He came home with many stories of its progress, including the loss of a man, fallen from the ceiling of the forum during his working on the project. I marveled at the enormity of the undertaking, never knowing what had been before.

He was already gone when I learned of the original station. I never had the opportunity to discuss the value of historic places with him. I wonder what he would have thought: Would he have believed in their worth, or been happy to see things torn down to bring in the new? It saddens me to see such glory demolished, and when I realize my father’s part in its undertaking, it makes me more adamant in the protection of the history we still posses.

great story , I ask the same questions

I have often wondered at the dissimilar architecture when walking from the 1,2,3 Subway into Penn Station. I always wondered where these brass fixtures and railings originally led? Thank you for explaining it at last. Perhaps the old post office building can now give us some sense of the grandeur the original Penn station had if they ever go ahead with the conversion and restoration. We can still dream and hope.

Hello,

I thought you or someone you know might be interested to know that I currently have listed on ebay a scarce 1910 New York Pennsylvania Station 36-page book created by the Pensylvania RR to showcase the opening of the Station. Tons of photos including one of the “Women’s Waiting Room”. It’s listed here:

http://www.ebay.com/itm/262910444319?ssPageName=STRK:MESELX:IT&_trksid=p3984.m1555.l2649

Please let me know if you have questions or need more information.

Sincerely,

Gayle Tinnerman

(619)501-5878 (San Diego)

Where did the clock go?