The Steinway Family, the master piano builders, transit magnates, and resort developers, and the Kreischers, the brick makers who left their mark on far-flung New York City neighborhoods, put a personal stamp on the neighborhoods in which they resided, and these stamps are visible even today.

Henry Steinweg, a German piano manufacturer, emigrated to New York City from Seesen, Germany, in 1853. His sons Henry Jr. and Theodore set about making pianos renowned the world over as the finest pianos ever made.

Henry Jr.’s and Theodore’s younger brother, William, continued the family tradition (advertising their instruments as “the standard piano of the world”) and moved the operations of Steinway Pianos to Astoria, Queens.

Between 1870 and 1873, Steinway purchased 400 acres of land in northern Astoria and not only built the spacious Steinway Piano Factory, which still dominates the area, but a small town with a library, a church, a kindergarten, housing for factory workers, and eventually a public trolley line.

William Steinway’s mansion, on 41st Street, still stands on a high hill that has never been leveled, unlike the surrounding area. 41st still looks like a country lane.

The mansion was built as a country home by optician Dr. Benjamin Pike in 1856, and was occupied by Pike’s widow for 10 years after his death in 1864. In 1874 William Steinway was running the piano maufacturing, having newly established it with his father and brothers in Astoria a few years earlier.

The Steinway family owned the mansion for the next fifty years, until selling to Turkish immigrant Jack Halberian, who divided it into boarding rooms for renters. Jack’s son, Michael, inherited the house and partially restored it to former magnificence. Michael passed away in early 2011, and his heirs did not feel confident they could maintain the 27-room mansion, and subsequently put it on the market. Here’s hoping any future owner will be able to maintain it.

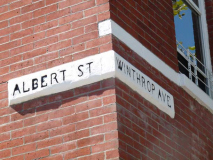

Between 1877 and 1879, Steinway constructed a group of handsome row houses on Winthrop Avenue (today’s 20th Avenue) and on Albert and Theodore (41st and 42nd) Streets. Even the street names bore witness to the Steinway family, since Albert and Theodore were sons of Henry Steinway. These homes were rented by the Steinways to their workers.

Had the Steinway family made their name on pianos alone, their reputation would be everlasting. But William Steinway was a person who can rightly be called a Renaissance man. He was also a transit magnate in the early days of trolley car operations. In 1894, as President of the Steinway Railway Company, he electrified his Long Island City railway that terminated at Northern Boulevard and Woodside Avenue, in a station that still stands. The line was soon extended to Corona.

In the mid-1890s, Steinway began a trolley expansion that would bring his lines into midtown Manhattan. Unfortunately, Steinway passed away before the tunnels could be completed. Later, IRT pioneer August Belmont completed the tunnels, which even today are called the Steinway Tunnels. Excavated detritus from the tunnel was formed into a 100′ x 200′ island in the middle of the East River, first called Belmont Island, but later renamed U Thant Island.

William Steinway also developed a resort area in North Beach (just east of Astoria), which, in 1939, became the North Beach Airport (soon to be renamed LaGuardia Airport).

But Steinway wasn’t the only New Yorker who built a company town…

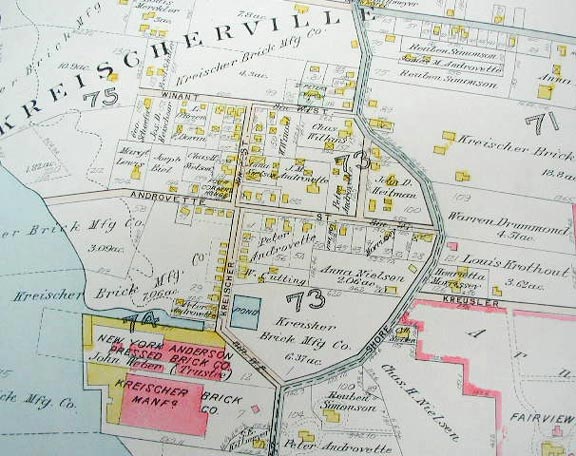

This map from the Belcher Hyde property atlas shows a small section of Charleston, Staten Island that was settled by Balthazar Kreischer, who built brick works beginning in 1854. This part of southwestern Staten Island is rich with clay pits. Unmined clay deposits can still be seen along Arthur Kill Road.

The Kreischer Mansion dominates Arthur Kill Road in Charleston, Staten Island.

In 1854, at about the same time that Henry Steinway Sr. was starting his piano empire, Balthazar Kreischer was building his brick factory in Charleston, Staten Island (Richmond County was then an independent city). Because of the clayey ground in the area (Clay Pond Park State Preserve is nearby), Kreischer’s was one of several brickmaking firms active in the period.

Balthazar’s son Charles constructed a grand mansion on Arthur Kill Road (much as Henry Steinway’s son William constructed a grand mansion of his own in Astoria) in 1885. The difference here is that Charles Kreischer’s brother Edward also constructed an identical mansion just to the south of Charles’. That mansion was torn down some decades ago.

It is rumored that Beatle George Harrison was at one time interested in buying the Kreischer mansion, but changed his mind when security concerns became a problem for the Quiet Beatle.

The Steinway and Kreischer families, of course, have Steinway Street and Kreischer Street named for them. Forgotten Fan Ellen Perroth, a Kreischerville resident, tells me that one of Balthasar’ Kreischer’s daughters married one of Steinway’s sons, so there is more of a connection between these two families than I had previously thought.

Also in a fashion very similar to William Steinway, Kreischer and Sons built housing leased by his brickworkers. These houses on Kreischer Street are quite old, dating back to 1865.

The products of the Kreischer brick works are ubiquitous in this area…sidewalks on Kreischer Street are made of them in addition to area buildings and fenceposts.

Probably nowhere in the city was as affected by the Kreischer brickworks as was Ridgewood, Queens. There, row upon row of Mathews Model Flats were faced with the handsome yellow brick fired in the Kreischer kilns. Astoria can also boast of several buildings built with Kreischer bricks.

Stockholm Street in Ridgewood was paved with Kreischer brick. The stones were restored several years ago on this landmarked block.

Nicholas Killmeyer originally owned this general store at Arthur Kill Road and Winant Place; it dates to approximately 1865.

Former post office at Kreischer and Androvette Streets, seen in 1903 and 2003. Kreischerville was a self-contained small town, with a post office, general store, church, school and even a cemetery.

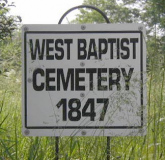

The small Baptist cemetery at Arthur Kill Road and Storer Avenue, just north of Kreischerville, predates the town by a few years. Even today, Charlestown is a place where everyone knows your name, and names on old Staten Island gravestones often turn up on street signs as well.

Nicholas Killmeyer, who had built the general store shown above, also built a roadhouse at Arthur Kill and Sharrotts Roads in the mid-1800s. Now known as Killmeyer’s Old Bavaria Inn, it boasts its original bar and dozens of brands of German bier. Oompah bands play on Sunday afternoons and rock bands play the beer garden in the back on summer evenings. Killmeyer’s was renovated in 1995. The gorgeous, intricate woodworked bar is reason enough to visit Killmeyer’s.

The Free Magyar (Hungarian) Reformed Church on Winant Place in Charleston was built by Charles Kreischer in 1883. It was originally known as St. Peter’s German Evangelical Lutheran Church. A piece of paper with an apparent handwritten signature of Balthazar Kreischer himself was recently uncovered in the church!

The church driveway fenceposts are Kreischer brick, what else….

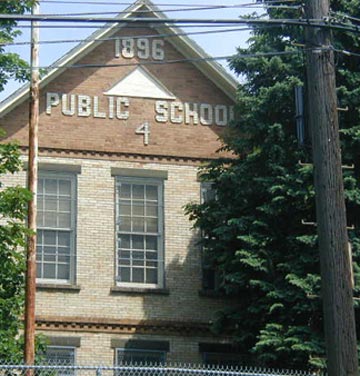

PS 4, on Arthur Kill Road across from the cemetery, is probably the edifice with the highest concentration of Kreischer brick in the area. It is still used by special ed students.

Clay Pit Pond Park

Clay Pit Ponds State Park Preserve is a 260 acre natural area near the southwest shore of Staten Island north and east of Kreischerville. Once the site of a clay-mining operation, the Park Preserve today contains a mixture of unique habitats such as wetlands, fields, sandy barrens, spring-fed streams and woodlands. As a terminal point for some northern & southern plant species, the area is rich with a variety of plant and animal life. A sampling of plants and animals found in the Park Preserve include pitch pine, lizard’s tail, raccoon, screech owl, box turtle and fence lizards, whose tails break off when they are disturbed.

Sandy Ground

If you know anything about Staten Island history, a walk along Bloomingdale Road and Crabtree Avenue can break your heart.

Oyster harvesting was a major business on Staten Island during the 1800’s and was mainly conducted on the Island’s south shore. The area of Prince’s Bay was the main hub and was within walking distance from Sandy Ground. It is here that men went out to rake oysters up from the ocean floor to be sent to Manhattan and other locations for sale. Sandy Ground, a small section of Charleston located along the two roads named above, was named for its inhospitable soil. In the mid-1800s it became a mecca for free blacks from Maryland who had heard of the outstanding oystering. Sandy Ground became one of the first communities for free blacks in the country.

Joseph Mitchell, in his collection of stories written for the New Yorker called Up In The Old Hotel (Vintage, 1992), has an article called “Mr. Hunter’s Grave” in which the caretaker of nearby St. Lukes’ Cemetery tells him about Sandy Ground:

“It’s a relic of the old Staten Island oyster-planting business. It was founded back before the Civil War by some free Negroes (sic) who came up here from the Eastern Shore of Maryland to work on the Staten Island oyster beds, and it used to be a flourishing community, a garden spot. Most of the people who live here now are decendants of the original free-Negro families, and most of them are related to each other by blood or marriage. Quite a few live in houses that were built by their grandfathers or great-grandfathers. On the outskirts of Sandy Ground, there’s a dirt lane running off Bloomingdale Road that’s called Crabtree Avenue, and down near the end of this lane is an old cemetery. It covers an acre and a half, maybe two acres, and it’s owned by the African Methodist Church in Sandy Ground, and the Sandy Ground families have been burying in it for a hundred years … they haven’t cleaned it off for years and years, and it’s choked with weeds and scrub. Most of the gravestones are hidden. It’s surrounded by woods and old fields, and you can’t always tell where the cemetery ends and the woods and fields begin…”

Very little of Sandy Ground’s physical past remains as tract housing continues its inexorable march through southern Staten Island. The Rossville AME Zion Church is a replacement for the original. A couple of original frame houses remain as well as what was the blacksmith. More can be learned at…

Sandy Ground Historical Society

1538 Woodrow Road

Rossville

(718) 317-5796

Thanks to Forgotten Fan Sharon Seitz for assistance with this page

3/2/2000; rev 2012

1 comment

Thanks for post this amazing. I’m a long time reader but ive never commented

till now.

Thanks again for the awesome post.