If there’s anything Greenwich Village is not, it’s Forgotten. Guidebooks spend dozens of pages pointing out the Village’s trendy spots and tourist attractions. But there’s a Village of centuries-old houses, hidden alleys and landmarks the guidebooks won’t show you. For example, Washington Square used to be a potters’ field and before that, a place of execution: the hanging tree is still there, at MacDougal and Waverly, just inside the park! Let’s take a brief look at the Village, Forgotten-style. We’ll begin with a triangle on a sidewalk.

This is the oldest house in Greenwich Village, at the corner of 77 Bedford Street and Commerce Street. Known as the Isaacs-Hendricks House, it was built in 1799 (before most of the Village streets had been laid out), although large sections of it including the brick facing were added in 1836, and the third floor is practically new, since it was added in 1928.

The Isaacs-Hendricks House is a former farmhouse owned by Harmon Hendricks, a copper merchant who supplied Robert Fulton with materials for copper boilers that powered the historic Clermont steamboat run in 1807.

Next door, in a house so narrow it rates only half an address, is 75-1/2 Bedford Street, a house only 9-1/2 feet wide. Shaquille O’Neal might have a hard time laying down on the floor. There used to be stables inside the block adjacent to the Isaacs-Hendricks House, and the narrow building was constructed in 1873 on what used to be the carriageway entrance. Famed poet Edna St. Vincent Millay lived in the building briefly in 1923-24. (Novelist William Burroughs lived at 69 Bedford, a few doors down, in the 1950s)

Directly across from 75-1/2 Bedford is this building at 70. It doesn’t look like much but it’s of note for having been here since 1807, at least the bottom two floors have. It was built by sailmaker John Roone in that year; Roone was also a court crier, the guy who yelled ‘oyez, oyez, oyez’ (in English, “listen”) that you may remember from some old movies.

Embedded in the sidewalk at the venerable Village Cigars shop at 7th Ave. South and Christopher Street, trod upon by hundreds of thousands of feet yet barely noticed, is a marker that reads:

“Property of the Hess Estate

which has never been dedicated for public purposes”

So what’s this all about?

There used to be a five-story residential building on Christopher Street called the Voorhis. It was condemned in the 1910s to make way for the IRT subway, which also extended 7th Avenue south from Greenwich Avenue. However, the Voorhis’ owner, David Hess, refused to surrender this small plot to the city to become part of 7th Avenue South’s new sidewalk. The Hesses created this mosaic to let everyone know of their small (VERY small) victory against the city.

Village Cigars moved to its present corner site in 1922, and bought the 500-square inchproperty from the Hesses for $1,000. The mosaic has stayed put.

At this diner at Bedford and Morton (which has an incredibly large menu if you’re ever in the area) they’ve kept the old grocery store sign complete with Pepsi Cola bottlecaps and ‘cold cuts’ sign.

2003: The restaurant, and its sign, have disappeared. Your webmaster ate there and it’s no wonder.

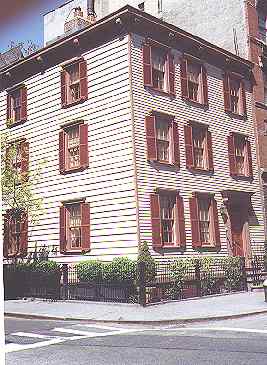

Some folks think this frame house on the corner of Grove and Bedford Streets is the oldest in the Village (as opposed to the Isaacs Hendricks House). It’s pretty old alright, but there are a fair number that are older.

Window sash maker Thomas Hyde built it in 1822 and typically of houses built at the time, it had only two stories when built with the third going up in the 1870s.

The three story building at the corner of Bleecker and Christopher is one of the oldest houses in Greenwich Village. It was built between 1802 and 1806 by William Patterson. For most of its life the ground floor served as a grocery; it is currently a Godfathers Pizzeria. Berenice Abbott shot a picture of it in 1935.

Next door at 102 Bedford Street, an 1830 townhouse was renovated beyond remembering in 1925 by Clifford Daily with help from financier Otto Kahn. Daily, an amateur architect, considered the surrounding buildings mundane and wanted to liven things up. But Kahn took over the building and offered Daily $5000 to clear out. Daily reluctantly agreed, but vowed to someday return. The story goes that he plunged two bottles of champagne in wet cement in the basement and said he would break them out when he returned to Twin Peaks. The bottles are still waiting.

“Great fun for the kids” says White and Willensky’s AIA Guide.

Christopher Street is the oldest east-west street in the Village, and was trafficked (as Skinner Road) as early as the late 1700s. Naval hero Peter Warren owned huge tracts of property in the area in the 1700s, but property was dived into lots in the early 1800s.

18 and 20 Christopher Street, above, date to 1827 and have kept their dormer windows (seen at the top through the foliage)

The Newgate State Prison (remembered in the IRT Christopher Street station mosaic, above) was opened at the foot of Christopher in 1797 and as unlikely as it sounds now, the prison spurred development on the street and residences and businesses began to be built on it. Some of them still stand.

13, 15 and 17 Christopher (above), as well as 23 and 25 (below) date from the same year, 1827, and were built by Samuel Whittemore, a textile manufacturer and state assemblyman. They are wood frame houses with brick fronts (added in subsequent decades).

Leaving the West Village, there are a couple of other homes scattered around the Village that have stories to tell…

In this four-story building at 85 West 3rd Street, Edgar Allan Poe lived and worked in 1845 and 1846. Some of his more famous works such as “The facts in the Case of M. Valdemar” (which was made into a movie starring, who else, Vincent Price) were written here.

Poe had three NYC residences: 85 Amity Street (renamed West 3rd soon after Poe left the house), a farm in what is today West 84th Street, and the Poe Cottage in Fordham, Bronx.

New York University Law School would like to tear this building down to make room for a new facility. Check this website for the latest on the fate of this historic building.

2003: New York University has demolished this building and has erected a giant monstrosity in its place.

Did I see a raven in the backyard?

For 70 years this building hosted the popular Italian restaurant, Bertolotti’s. There was also a club called The Gold Bug, a title Poe aficionados would know about.

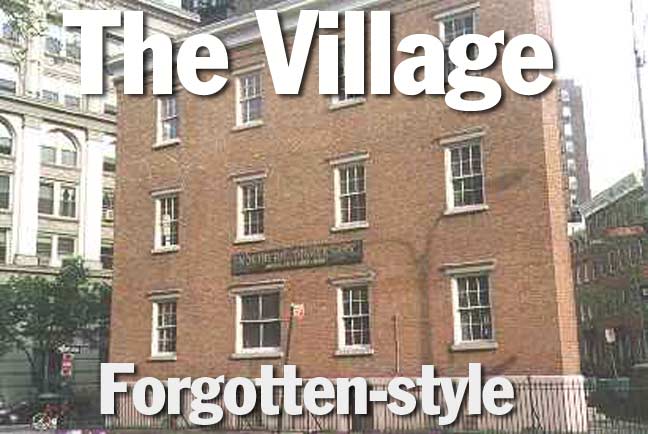

Because of a geographical quirk (Waverly Place splits in two) , the triangular Northern Dispensary has two walls facing Waverly Place and the other wall facing Grove and Christopher Streets. From 1831 to the late 1980s, free medical treatment was available here. The sign for dental service no longer applies. The Greenwich Savings Bank was founded in this building in the 1830s.

Sullivan Street has a few early 19th century relics…

83-85 Sullivan dates to 1819. As is usually the case the third floor was added at a later date.

57 Sullivan goes back to 1817.

On West 11th Street west of Sixth, Henry Brevoort built seven houses numbering 14 through 26. in 1844. Most (except No. 20) have been altered to some degree, but #18 has been changed beyond recognition.

That’s because the original No. 18 is no longer there; it was destroyed by terrorists in March 1970.

To be brief, the Weathermen were a domestic terrorist group dedicated, among other things, to the fall of the US government. Five members of the organization had set up a bomb factory in the basement of No. 18 to destroy the Columbia University Library. But on March 6, 1970, some of their dynamite cache accidentally exploded. Three terrorists were killed; two, Cathlyn Wilkerson and Kathy Boudin, escaped and avoided capture for more than a decade. Actor Dustin Hoffman and his family resided at 16 West 11th at the time and suffered extensive damage to his apartment.

The site itself remained vacant for eight years. No. 18 was reconstructed in 1978 by architect Hugh Hardy, featuring a facade that swings 45 degrees from the street line, as a subtle reminder of the blast long ago.

In a homey touch, the current owners keep a Paddington Bear in the window and change its outfit to match whatever the current weather happens to be.

This is the hangin’ tree of Washington Square Park.

The park has had many uses…in the late 1700s and early 1800s alone it was a potters’ field for cholera epidemic victims, a military parade ground, and a place of execution.

This elm, in the northwest corner of the park, was used for executions until 1819. It is one of the oldest trees on Manhattan Island; some botanists believe it has been there for 250 to 300 years.

In the late 1800s excavations in the vaults under WSP revealed corpses still bearing traces of their funeral shrouds.

One last trace of the hangman has vanished from the tree in recent years. In 1992 the Parks Department cut off the arm where the actual hangings took place.

SOURCES:

Greenwich Village and How It Got That Way, Terry Miller, 1990 Crown.

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

Seeing New York, Hope Cooke, 1995 Temple University Press.

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

Greenwich Village, Culture and Counterculture, Rick Beard and Leslie Cohen Berlowitz, eds., 1993 Museum of the City of New York.

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

“The House On West 11th Street”, Mel Gussow, New York Times, March 5, 2000

6/5/2000

1 comment

[…] credits Greenwich Village and How It Got That Way (Terry Miller, 1990 Crown) for the information GREENWICH VILLAGE, Manhattan | | Forgotten New York […]

Comments are closed.