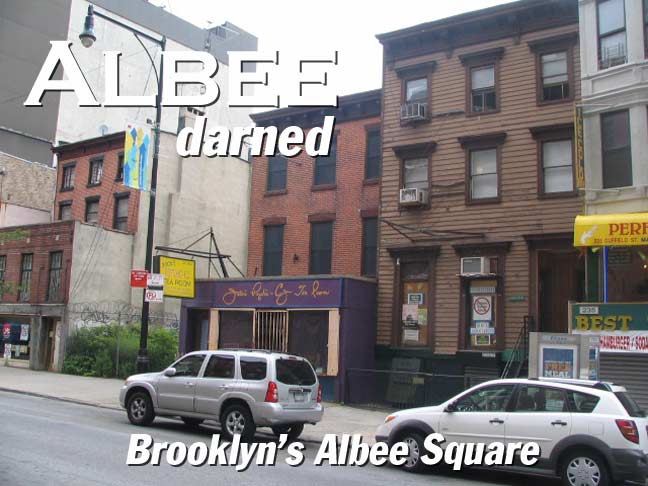

On what turned out to be a cool, cloudy 4th of July, 2007 your webmaster invaded one of those Brooklyn neighborhoods that seems to have been caught between two more highly-publicized ones: that nebulous region between Brooklyn Heights and Fort Greene, anchored by the Fulton Mall and known on maps merely as “Downtown Brooklyn.” Roughly speaking, it runs between Jay Street on the west, Flatbush Avenue Extension on the east, Fulton south and Nassau Street north. We’ll call it Albee Square, which seems to be as good a name as any.

It’s been prime hunting grounds for developers and urban planners over the years, with wide swaths of it carved out for public housing (1930s-1940s), the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and Cadman Plaza (1950s), and MetroTech (1980s), and as the area seems once again to be on the cusp of major development, let’s take a look at what we’ve got in the mid-to-late 2000s…

WAYFARING: ALBEE SQUARE (open in separate window)

Albee’s Anchor

As we’ll see, many of Brooklyn’s lengthiest roads converge in Albee Square. DeKalb Avenue begins a meandering journey to Ridgewood here, and at 9 DeKalb you will find the magnificently domed Dime Savings Bank, which, I believe, has been converted to Washington Mutual, although I couldn’t confirm that due to the constant renovations and scaffolding that envelop many NY buildings. (Ironically, the beautifully-designed buildings I prefer are, in most cases, quite old, which means they demand constant TLC). The Dime Savings Bank as an institution was founded in Brooklyn in 1859.

The Dime is an Ionic-columned neo-Classical palace built between 1906 and 1908 by architects Mowbray and Uffinger. The interior is one of Brooklyn’s most magnificent indoor spaces: the central dome is defined indoors by a ring of twelve marble Corinthian columns crowned, at the top, by gilded representations of the obverse and reverse of the “Mercury” Dime. Since “Mercury” dimes were issued between 1916 and 1945 these must have been added sometime after the bank was opened in 1908.

“Mercury” dimes don’t depict the Roman messenger god; the representation of Miss Liberty wearing a winged cap merely resembles him, hence the nickname. The reverse is a design of a Roman symbol of authority, a bundle of birch rods tied together with an ax, known as the fasces. Unfortunately Italy’s Benito Mussolini‘s authoritarian national party, the Fascists, co-opted the symbol as early as 1919.

A gilded eternity. Though covered in gold paint here, “Mercury” dimes were actually 90% silver.

The Father of Albee Square

The Father of Albee Square

Benjamin Franklin Keith (1867-1914) and Edward Franklin Albeebecame partners in the late 1880s to promote “polite” vaudeville. They lavishly remodeled several theaters on the east coast and began producing a brand of “high class” vaudeville. Crude remarks and risqué costumes were censored from performances (then why go? –your webmaster) and they even attempted to prohibit rude behavior by audiences. Keith was the financial head of the circuit, while Albee was the general manager and owner of several theaters. In 1906, Keith and Albee established the United Booking Office. Every act that sought employment at any of the member theaters had to work through this central office, which in turn charged a five percent commission per act. Thus Keith and Albee expanded their power base. In the 1920s the Keith/Albee circuit merged with a western chain of vaudeville theaters to form the Keith-Albee-Orpheum Circuit. In 1928, $4,500,000 worth of stock was sold to Joseph P. Kennedy’s Radio Corporation of America (RCA) establishing the Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO). After this merger, motion pictures became the primary form of entertainment, while vaudeville survived only as an accompaniment to the feature film. [University of Iowa].

Edward Franklin Albee III (1928- ), the adopted son of Edward Franklin Albee’s son Reed Albee, is the playwright of the Tony-Award-winning Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf , The Sandbox and many others, and is still going strong today.

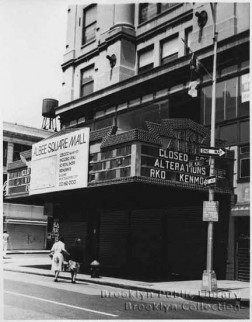

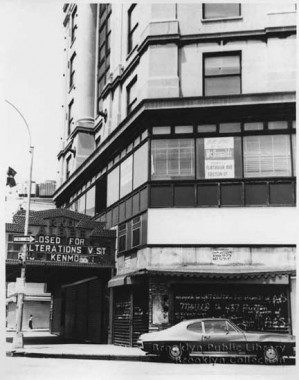

RKO Albee in the late 1970s. They weren’t kidding about the alterations. Brooklyn Public Library, via cinematreasures

The Beaux-Arts Albee Theatre, designed by Thomas Lamb, opened in 1925. The Albee was always considered one of the most important and beautiful theatres in Brooklyn. In its first years, it played two-a-day vaudeville exclusively, but finally had to give into the competition by adding a feature movie and shifting to continuous performances. Vaudeville was finally dropped in 1934-35 when it became economically unfeasible due to the Depression. As the RKO Albee, it was exclusive first-run for all of Brooklyn, getting the movies direct from their Broadway premiere engagements. However, due to the product “split” between three other downtown Brooklyn palaces– the Fox, Metropolitan, and Paramount– the Albee played mainly 20th Century-Fox and RKO releases. This meant, as it did with the other three theatres, that the double-feature programs usually had to be “held-over” for at least one extra week, which was not rewarding except in the cases of the biggest hit movies. Because of its size, the Albee suffered when the New York area switched to the “Premiere Showcase” type of saturation release and the theatre lost its exclusive status. Due to a simultaneous decline in downtown Brooklyn’s shopping district, the Albee’s demolition seemed inevitable as the community tried to save itself with new construction projects. cinematreasures

Gallery at Fulton Mall, site of Albee Square Theatre, July 4, 2007. Your webmaster never got inside the Albee, though along with the former Kenmore in Flatbush, I always admired its black marquee and white letters; that set it apart for me. I’m a relative Johnny-come-lately to the architrectural treasures of downtown Brooklyn, especially the interiors, having visited only rarely the magnificent insides of the Dime and Williamsburg Savings Banks, or the Paramount Theatre, whose organ still accompanies Long Island University sports. I have been inside what was then known as the Albee Square Mall only once, in 1979, to buy a 45 (remember those?) The record? The Vapors‘ “Turning Japanese.”

In the late 1970s Fulton Street underwent a major transformation as it was narrowed to just two traffic lanes, some extremely ugly signage and shelters were constructed, and the whole shebang became known as Fulton Mall. The whole thing was completely incongruous to Fulton Street’s classic architecture, which included, and still does, gems like the old Gage and Tollner restaurant (in 2007, the landmarked space was looking for a tenant) and Abraham and Straus Department Store, since become part of Macyworld. As part of the renewal, the old RKO Albee, seen on its last legs in the pix above, was razed and the Gallery built in its place.

At this point it seems as if the Gallery, too, is soon to go as yet another developer, buoyed by a public subsidy, seems set to build a massive 50-60 story residential/commercial tower here.

Esthetics aside, Fulton Mall has been wildly popular with middle class Brooklynites, who trek into the area from Fort Greene, Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn Heights, and Cobble Hill for its bargains. That doesn’t sit well with Brooklyn’s present-day mega-developers, who are searching for a way to make the area more upscale.

At some point in the past few decades, Gold Street, which used to run all the way south to DeKalb, was renamed Albee Square West south of Flatbush Avenue Extension, following the London, UK practice of calling streets “squares.” The block between DeKalb and Willoughby Street is mostly filled with plain office buildings and parking lots, but there are a couple of older residential buildings left, likely remnants of Gold Street’s earlier status.

At Willoughby Street and Albee Square West is the massive 25-story 4 MetroTech Center, completed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in 1993 on the Southeast corner of the MetroTech complex. It’s primarily occupied by JP Morgan Chase, whose logo crowns the building.

Duffield Street is one of two streets in Brooklyn to end in -ffield. The other one is Sheffield Avenue in East New York. It was named for Revolution-era Brooklyn Village surgeon John Duffield; a long-vanished parallel street, Barbarin Street, was also named for a doctor.

At Duffield and Fulton, we see a couple examples of design from the 1970s (left, a Fulton Mall stanchion) and 19-oh’s (a closed entrance to the Hoyt Street station of the IRT subway likely dates to 1908 and uses ironwork long-abandoned on most routes, though the style continues on IRT el stations in Manhattan and the Bronx).

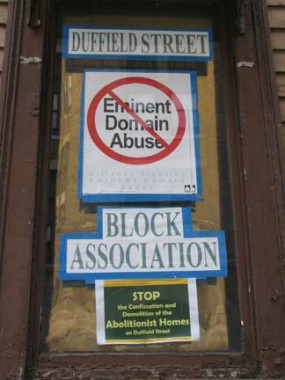

A group of buildings at 225, 231, 235, 223, 227 and 233 Duffield are believed to date to the Civil War era and are further believed by their owners to be former homes of abolitionists, if not stops on the Underground Railroad, as was the nearby 1846 First Free Congregational Church, later the African Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal Church on Bridge Street south of Johnson Street in MetroTech Center.

The city has plans to seize the houses via eminent domain, demolish most of the houses on this stretch of Duffield and replace them mostly with parking spaces, and further develop 500 new hotel rooms, 1,000 units of mixed income housing, more than 500,000 square feet of retail space and at least 125,000 square feet of new office space in the area.

The city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) appears to be washing its hands of involvement with three endangered Duffield Street houses which are linked to the Underground Railroad and the anti-slavery movement in mid-19th century Brooklyn.

In a May 28th letter to Peg Breen, the president of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, LPC Commissioner Robert Tierney said, “Given the dramatic changes that will occur to the streetscape of Duffield Street, I believe the commemoration of the important role Brooklyn has played in the history of abolitionism will be better served by the program of memorialization referenced by EDC (the city’s Economic Development Corporation) and the City Council than by preserving the three buildings.” [Brooklyn Graphic]

We’ve seen the LPC’s reluctance to get involved with altered yet historic buildings before.

The city hired consulting firm AKRF, which has conveniently failed to find any reason to preserve the houses.

A new city report has again cast doubt on claims by residents of Duffield Street that their Downtown Brooklyn houses were part of the Underground Railroad.

A city-hired consulting firm revealed this week that there is no conclusive evidence that seven houses on Duffield and Gold streets were part of the fabled fugitive slave network.

“It [the Duffield houses] … does not have a significant association with a national figure of the Underground Railroad and his/her Underground Railroad activity,” the report concluded.

The report by AKRF, a consulting firm that researches historic claims, also refuted residents’ contention that the buildings were connected to known abolitionists.

“Of course they’re going to say that,” said Joy Chatel, the owner of 227 Duffield St. “They’re trying to whitewash the truth — that my house was part of the Underground Railroad, and that it was owned by known abolitionists.” [Brooklyn Paper]

There is a firm called AKRF which has 25 years experience in squelching opposition to big development projects. They recently undertook their longest venture in historical analysis: Two and a half years devoted to trying to deny the claims that Duffield Street in Downtown Brooklyn was part of the Underground Railroad of the Civil War era. They failed spectacularly. Abolitionists who walked the streets of Downtown Brooklyn would be proud. [Underground Railroad Safe Houses]

The stretch of Duffield between Fulton and Willoughby contains a number of buildings from various eras and constructed with differing architectural styles.

Most of their residents believe they’re worth saving.

Willoughby Street, which becomes Willoughby Avenue east of Fort Greene Park and runs all the way to Ridgewood a la DeKalb Avenue, was named for colonial-era businessman Samuel Willoughby, who married into the Duffield family.

At 101 Willoughby (aka 7 MetroTech Center) at Bridge Street is the 1931 Art Deco NY Telephone Company building, constructed by Ralph Walker, who worked chiefly in Art Deco (he also designed the Western Union Building at 60 Hudson Street in Tribeca).

As Belltel Lofts, it is now a premier residential building, as the attempted upscaling of Albee Square continues.

As we see on the opposite corner of Willoughby and Bridge, though, Albee Square’s traditional character is yielding only slowly. Broadway Bakery was doing very good business on the early afternoon of July 4th.

“Oh denial,” shouted Cobain from a passing car radio.

St. Joseph High School is a small (300 students) Catholic girls’ high school at 80 Willoughby. It’s unusual to see an icon of a saint on the side of an office/residential building; St. Joseph’s occupies the bottom two floors of 80 Willoughby.

Bridge Street was named for a grand project that never materialized. A bridge was going to be built in the early 1800s from its northern limit in DUMBO to Manhattan’s Corlears Hook. The plans never materialized. Later of course the Brooklyn (1883) and Manhattan (1909) Bridges were built.

Perhaps we’ll have a Moynihan Station Street, Atlantic Yards Street and Second Avenue Subway Street to honor other projects that might or might not be scuttled down the line.

“Bridge Cleaners”? I thought the Department of Transportation did that. Actually this was the dry cleaner’s former location, Bridge Street between Willoughby and Fulton. This design gets the Brooklyn Bridge’s diagonal cables pretty much right.

I found its new location in an unusual manner…

…just followed the yellow steps up the street to Bridge Cleaners’ new home.

Brooklyn Uniform Center at 390 Bridge has a colorful window painting of tropical birds, signed by the artist.

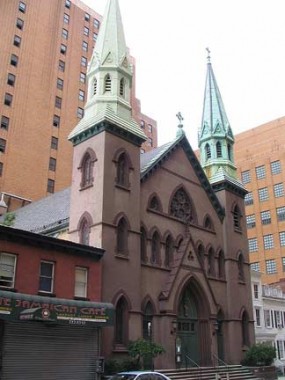

Returning to Duffield Street, north of Willoughby there is a group of interesting buildings, if only for their staying power. This Roman Catholic church at 190 has alengthy name: The Catholic Church of St. Boniface Under the Supervision of St. Philip Neri.

The early parishioners of St. Boniface took heart from recalling their patron’s own struggles to feel at home in a foreign land with a foreign language. The parish thrived in those early years, and by the late 1860s it was obvious they needed a larger church. They purchased land on Duffield Street and began to build a new edifice designed by the most famous Catholic architect of the day, Patrick Keely. The charming little neo-gothic structure was completed and dedicated on January 29, 1872, the 18th anniversary of the founding of the parish. The new church was built for a cost of $40,000. [oratory-church.org]

Duffield between Willoughby and Myrtle Avenue was renamed, or rather, suffixed, Oratory Place in honor of the church by the NY City Council in 1993.

The Duffield Street Houses, 182, 184, 186 and 188, just north of St. Boniface, have been designated NYC landmarks since 2001. When Metrotech was constructed along part of Johnson Street (Tech Place) from 1989-1995 the houses were moved here. They were built by Johnson Street’s namesake Samuel Johnson in the early 1800s.

However: it strikes your webmaster as somewhat odd that 225, 231, 235, 223, 227 and 233 Duffield (see above), which have been on Duffield all along and are purported to have more history behind them, have not been so designated.

MetroTech is a sprawling (nearly 6 million sq. feet) business and education center located between Tillary Street, Myrtle Avenue, Adams Street and the Flatbush Avenue Extension. Noted occupants of this area include JPMorgan Chase , FDNY Headquarters, Bear Stearns, Keyspan Energy and Polytechnic University, and the Marriott Hotel — Brooklyn’s first hotel in decades when it opened in the early 1990s.

MetroTech is adminstrated by Forest City Ratner, the same firm that proposes to build the controversial Atlantic Yards project.

We’ve said before that Albee Square is a place where some of Brooklyn’s longest roads originate. Here, two of them meet: Myrtle Avenue (top) and Flatbush Avenue Extension (bottom). When the Manhattan Bridge was completed in 1909, the dawn of the auto age, a roadway was built connecting the bridge to the junction of Fulton Street and Flatbush Avenue; Flatbush, before that, began at Fulton. Rather than renumber the lengthy avenue, the new avenue was called Flatbush Avenue Extension. The Manhattan Bridge, alone among NYC’s major bridges, does not offer a direct connection to a parkway or expressway, though NYC’s “master builder” Robert Moses did propose a Trans-Manhattan Expressway that would connect the Manhattan Bridge and the Holland Tunnel. Some support beams for the expressway were built and can be seen on the Manhattan side.

A view of Myrtle Avenue uncovered by an elevated train line wouldn’t have been possible here from September 1888 to October 1969, when the Myrtle Avenue el rattled in this spot. Your webmaster’s first view of this corner came in mid-1964, when I was here for something or other with my mother, and the first thing I noticed was that the el crossed Flatbush Avenue Extension on a fairly substantial arch, similar to the one the IND uses to cross 4th Avenue in Park Slope. The arch must have been built after the el was completed in 1888, since Flatbush Avenue wasn’t extended here till 1909. How do I know it was 1964? I remember Millie Small’s “My Boy Lollipop” a hit from that year, playing on a car radio. If anyone has a picture of that arch,send it over. (Someone does! see below)

Myrtle Avenue is an east/west thoroughfare which runs from the Flatbush Avenue extension through Brooklyn to Richmond Hill in Queens. It has been a major roadway since at least the early 1800’s and was named for the myrtle trees that once grew in the area. In Queens, it probably began as a “plank road,” or wooden road, for which a toll was charged. In the mid-nineteenth century, Myrtle Avenue hosted a bustling stagecoach, or omnibus, line run by the Knickerbocker Stage Coach Line.[myrtleavenue.org]

Flatbush Avenue Extension at Myrtle Avenue, ca. 1920. Note the clock tower at right; see below. courtesy Herb Schonhaut

Some old buildings and businesses at Flatbush and Myrtle are being torn down for what else, luxury condos, so these are really the last buildings in the area, save the Ingersolll and University Heights Houses (seen behind the Olds ad), that saw the el. Harper Olds disappeared Lord knows when. Oldsmobile made cars between 1897 and 2004.

A structure known as Oro Condos is being built in the triangle defined by The Flatbush Avenue Extension, Gold, and Johnson Streets. Often, new condos are accompanied by ads showing rich, smartly dressed young people.

They should have made it black and white and called it Oreocondo. Not everyone will get that oro means gold and it’s on Gold Street. Or will they?

NYC and Brooklyn, in particular, are blessed with a great number of clock towers, and not just on office buildings…they’re on schools, factories and even warehouses, like the one on Gold Street just off Flatbush. In the everlovin’ Eighties, this building was awash in gold paint.

Returning for the second time to Duffield Street, we find, between Tillary and Concord Streets, a throwback ro what the entire Albee square region may have looked like before housing projects, factories, expressways, extensions, and luxury condos in turn made their way onto the stage. Duffield here, and a short section of Concord, is tree-lined with either small detached houses or attached brick buildings.

We’re looking at Duffield here from the Concord Street side, with Orocondo and 7 Metrotech forming the backdrop, both beetling reminders of what the future holds for this area.

Already, all is not well on this throwback block. A backhoe here, a demolished building there. It looks like we won’t be throwing back much longer here at least. Except to drink and drown your sorrows at the death of old Brooklyn. How many of these buildings can hang in there with mega-development surrounding them? Of course the folks in Oreocondo will applaud the demolition of what they consider to be these eyesores.

This area should really be landmarked but no one has ever seen it except your webmaster and the streets’ residents.

From the ForgottenBook:

On 167 Concord, just east of Flatbush, I found a small dormered house, a neat picket fence, and an almost absurdly small car parked in the front yard. I discovered that the car, the Didik Long Ranger (Vanguard Citicar), is a hybrid gasoline/electric powered vehicle designed in the mid-1980s. It’s 96 inches long, 65 inches wide and 56 inches high and can comfortably seat three people. It can travel about 70-100 miles per charge, but the gasoline engine can power it only to a top speed of 30 MPH. It also contains solar panels to assist in charging the batteries.

The house is among the oldest in the neighborhood. It was built in 1762 and is surrounded by a stone wall dating to about 1820. The house is rumored to have participated in the Underground Railroad in the pre-Civil war era, like the houses on Duffield Street shown above.

I was lucky enough to learn about both the car and the house from their owner…Frank Didik, inventor of the Long Ranger as well as other electric-powered vehicles such as the Didik Sun Shark, a solar-powered motorcycle, and the Didik Duplexity, a foldable scooter that rides three people.

Community garden, Concord and Bridge Streets

The Bridgeview is a big ugly tower on Bridge Street we needn’t trouble. Wouldn’t surprise me if the old Howard Clothes building condo’ed up, though that hasn’t happened yet. This is at Concord and Flatbush.

This concrete, weedy plaza, between Concord and Nassau at Flatbush, is at the Brooklyn end of the Manhattan Bridge. Given that the Manhattan end features an expansive colonnade designed by Carrere and Hastings, based on Paris’ Porte St.-Denis, seen on this page. Oh well it’s the Manhattan Bridge.

There’s a palimpsest of ads on an adjoining building; I can make out one for Uneeda Biscuit. Ineeda rest…but there were still a couple of other buildings to see…

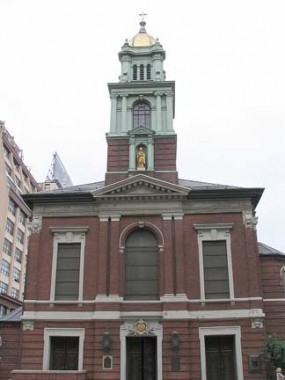

The Cathedral Basilica of St. James, Jay Street between the appropriately-named Chapel Street and Cathedral Place, was built in Neo-Georgian style in 1903, replacing the first cathedral built in 1822. Between 1896 and 1972 it was “demoted” to Pro-Cathedral, as there were grand plans for a bigger brooklyn cathedral, Immaculate Conception Cathedral, but it never worked out and this relatively modest building has been the seat of the Bishop of the Brooklyn Diocese ever since.

Plaques by the front entrance give a short history of the building, and note Pope John Paul II’s visit in October 1979.

The “PX” above the door are actually the Greek letters “chi” and “rho”. “Chi” and “rho” are the first two letters in the Greek word Christos or “Christ”.

Beside JPII on the plaque we see his papal coat of arms. Beginning in the medieval era, most popes have had one.

Papal coats of arms feature a gold and silver key. Matthew 16: 18-19: “You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

Pope Benedict XVI is the first Pope not to use the papal tiara on his coat of arms. He instead uses the papal mitre.

There seems to be no architectural information online or any of my reference tomes on George Westinghouse Information Technology High School, between Tech Place (Johnson Street), Tillary, Adams and Jay Streets, and it’s a shame…it looks as if it ought to be a landmark, with its ogee-curved doorways and windows and Guastavino tiles under the entrance arch.

Article from Brooklyn Eagle 4/24/07:

“Barbra Joan Streisand was born in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn on April 24, 1942. Her father, Emanuel Streisand, was a well-liked teacher of English, history, and psychology at the Brooklyn High School for Specialty Trades (which became Westinghouse in 1947), and also taught at a yeshiva school after hours. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1943.” courtesy Herb Schonhaut

Photographed July 4, 2007; page completed July 9.

erpietri@earthlink.net

©2007