All five boroughs have a Main Street, there are some streets you might think are in the wrong borough, and all five have a Broadway. The Bronx’ Broadway, though, is an extension of Manhattan’s Broadway, which has existed from antiquity first as an Indian trail that ran the length of Manhattan Island, then as a colonial trail that was subsequently straightened and widened, taking over the Bloomingdale Road that led to the Manhattan village of that name. The name is famous worldwide — I don’t know how many of the world’s cities have a Broadway (or words that mean ‘broadway’) in whatever language is spoken in those cities; I know London, UK has Fulham Broadway — but I have no idea if it was inspired New York’s.

The Broadway that begins with Number 1, the International Merchant Marine Building at Bowling Green, has been extended far upstate by a gradual process of street renamings. The route upstate more or less traces the path of the Albany Post Road, and by extension, Broadway is a continuous route by way of US 9 north almost all the way to the Canadian border. It is called Broadway continuously all the way north to Phelps Way (State Route 117) in Sleepy Hollow (North Tarrytown) whereupon the route assumes the name Albany Post Road. Route 9 assumes the name Broadway briefly once again in upstate Red Hook and again in Saratoga Springs. Route 9 completes its northern progress at a dead end along the Adirondack Northway (Interstate 87) north of the town of Champlain just south of the Canadian border.

Walking the whole length of Broadway and Route 9 upstate would be a prodigious task — for your plodding webmaster, it’d probably take an entire season. With pre-planning, for lodging and meals, it could possibly be done, even though some detouring would be necessary since Route 9 encompasses some pretty busy pedal to the metal traffic upstate, even though the Thruway and Northway carry the heaviest traffic. I decided for now to walk Broadway in the Bronx, which does not require an entire season but merely most of an afternoon. I alit on the #1 uptown train at the 215th Street stop, the last one in Manhattan Island, but, as we’ll see, not the last one in Manhattan, and am immediately greeted by a huge smokestacked sanitation plant.

There must be a couple of true Iron Maiden style entrance/exit turnstiles left in the subway system — the ones with a huge slab of metal that in the pre-Metrocard era requited a token in a slot and a push-down metal contraption –but these items, with straight bars, are getting pretty scarce too. It was made in the Tertiary Epoch by Perey Turnstiles, which is still in business.

Nine is the number in northern Manhattan as State Route 9 signs are posted regularly along the route. State routes, at least in urban areas, have lessened in importance as the superhighways tend to elevate over intersections, or are in outlying sections where there aren’t any pasky intersecting streets, but up till the mid-50s, Route 9 was one of the major routes from NYC to its northern suburbs in Westchester County. Just south of the Harlem River, Broadway encounters its final numbered avenue, 9th. It meets 5th Avenue between 23rd and 24th; 6th between 33rd and 34th; 7th between 43rd and 45th (the two routes fuse into a single wide entity north of Times Square for a couple of blocks); and 8th at Columbus Circle. It meets Columbus Avenue, 9th Avenue’s northern extension, at West 65th; Amsterdam Avenue, (10th Avenue), between West 71st and 72nd; West End Avenue (11th Avenue) at West 107th. Broadway makes a northeast turn in upper Manhattan and so meets 10th Avenue “again” between West 215th and West 216th, and finally, here, the northern stub of 9th.

I noticed the next day in an MTA email that the Broadway Bridge was raised to let a ship pass; I would have liked to get a photo of that, but it would have delayed my northern progress.

The language of this sign, “leave draw when gong sounds” appears on all the drawbridges that cross the Harlem River between Manhattan and the Bronx. I’ve never ben around when any of them have been raised and hence, have never heard the gong.

The sign is in magnificent Highway Gothic, variations of which are used in directional and street signs, avoiding the by-now clichéd Helvetica.

Crossing the mighty Harlem River. The New York Central tracks, which carry both Amtrak trains to Albany and points north, and Metro-North trains to Poughkeepsie, parallel the river.

We have crossed the Harlem River but we are still in Manhattan. In 1916 the river was dredged and straightened to make it suitable for heavy ship traffic and a small piece of the northern tip of Manhattan (Marble Hill) was thereupon orphaned. The Harlem’s old course was attached to the mainland by landfill, but that small slice of Manhattan has never lost its identity and so, Marble Hill is the only piece of Manhattan on mainland USA.

Marble Hill Houses is a drabbish housing project straddling Broadway on either side north of West 225th. Nothing interesting here you say? Christina (the Queen of Queens) worked up here a few years ago and found something interesting on the side of one of the buildings… a plaque explaining the history of Kingsbridge, the Harlem river crossing that launched a thousand Bronx place names.

As first noted on FNY’s Spuyten Duyvil page, the plaque says:

“Northwest of this tablet within a distance of 100 feet stood the original Kings Bridge and its successors from 1693 until 1913 when Spuyten Duyvil Creek was filled up.

“Over it marched the troops of both armies during the American Revolution and its possession controlled the land approach to New York City.

“General George Washington rested at Kings Bridge the night of June 26, 1776 while en route from Philadelphia to Cambridge to assume command of the Continental Army.

“This tablet was erected by the Empire State Society Sons of the American Revolution, June 27, 1914.”

Frederick Philipse built the first Kings Bridge, a tolled span over Spuyten Duyvil Creek,(since filled in) in 1693. Benjamin Palmer and Jacob Dyckman built a second bridge in 1759 to avoid paying the high tolls charged by Philipse. During his retreat from the Battle of Harlem Heights in 1776, General George Washington used both the King’s Bridge and Palmer and Dyckman’s free bridge to escape to White Plains. The original Kings Bridge has inspired a network of roads in Manhattan and the Bronx, some surviving, some not, named for it.

Once north of West 230th Street we have indeed left Manhattan and Broadway has attained the Bronx. It’s as good a time as any to discuss lightposts; there are a number of unique ones along today’s route. Broadway under the IRT el was, for several years in the 1970s and 1980s, illuminated by lantern-style posts, and still is north of here (see below). In the 2000s many of them have been replaced by the Thomas & Betts luminaire you see here.

I’ve photographed this Type 24M bishop crook on numerous occasions but this is the first time I’ve tackled it with a Canon S1-IS zoom lens. Really shows off the rust. The DOT typically does not paint poles with a large amount of rust, so this pole is probably doomed to die of rust poisoning; after awhile, a rusting pole will list so badly a car kills it, or the city is forced to remove it. Enjoy this relic while it’s still here on the west side of Broadway north of West 230th.

From the 1910s through the early 1960s Manhattan and the Bronx shared a street sign design: navy blue and white — by coincidence, the colors of the New York Yankees. The entire borough of the Bronx was annexed to NYC in stages in the years 1874 (west of the Bronx river, in general), 1895 (east of the Bronx River) and 1896 (City Island); they had been a part of Westchester County. The annexed regions became a new county, the Bronx, in 1914. Because Bronx streets were part of New York County along with Manhattan, they shared a street sign design.

From 1964-through the late 1980s, New York City enjoyed a brief interregnum when boroughs were marked by color-coded signs, so in those areas where two boroughs bordered each other, such as Marble Hill-Riverdale, Bushwick-Ridgewood, or Cypress Hills-Woodhaven, it was a simple matter to determine what borough you were in. In the 1980s the federal government mandated eye-ease green on most street signs, and all signs were gradually switched to green over the next few years beginning in 1985; color-coding boroughs was considered expendable. A few of the color coded signs remain, or remained till recently, like this one on Jerome Avenue.

There are a number of dead-end streets lining Broadway on the east side of the street between West 230th and West 238th. The reason for this is an abandoned railroad cut — the Putnam Branch of New York Central, which abandoned passenger traffic in 1958 and freight in 1980; it’s part of the John Muir nature trail along its stretch in Van Cortlandt Park, and, well, a rubble-strewn ditch south of the park, as NYC hardly ever converts old right-of-ways to urban trails. (If one neighbor protests, that’s enough to kill any conversion).

Verveelen Place is one of these dead ends and it is of particular interest, at least to Forgottenphiles, since it features a 1950-vintage Type 12S single-curved mast post. Curved-mast was the style of the very first streamlined octagonal-shaft lampposts in 1950, and the “octa-poles”dominate even today.

We also find a couple of vintage painted ads –I’d estimate from the 1940s or 50s — visible on Verveelen Place. The businesses they advertised left Broadway decades ago.

According to the late great Bronx historian John McNamara, Verveelen Place is named for ferryman Johannes Verveelen, who owned a nearby tavern in the late 17th Century. It was still in use during the Revolutionary War. Verveelen Place itself opened in 1922.

West 231st Street station. The street itself had to be run through solid Manhattan schist, which was either chiseled or dynamited away. early photos of this station, and West 231st, show boulders along both sides of the street.

All elevated stations in Manhattan and the Bronx are pretty cut from the same cookie cutter, but it was an intricately pretty one. The rails all feature the same motif, which looks inspired by the three pawnbrokers’ balls or perhaps the suit of clubs in a deck of playing cards.

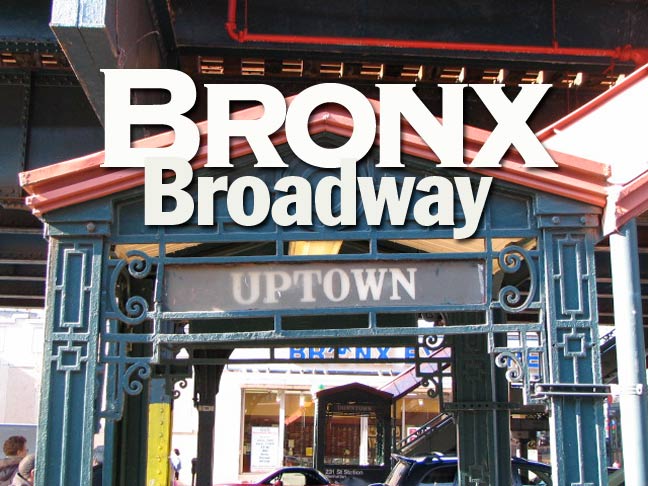

The covered staircases are marked UPTOWN and DOWNTOWN, the signs staying safe behind glass or plexiglass.

Note the white-green “station open” indicator globe. This is a 1990s version; we’ll see an older version a little later on.

North of West 231st. Keenan’s, as the sign says, was incorporated 1961. For a long time I was used to seeing much older dates on “established in…” signs. I saw an “established 1973 or 74” sign on a pub on East 14th awhile ago, and now this. I suppose the 1960s and 1970s are now sufficiently remote to warrant this kind of sign. Have you seen the 2008 ABC TV show “Life On Mars“? A detective is hit by a car and wakes up in 1973. It is so different a world, from this future time, that it might have been a different planet. Yet there are enough familar touchstones that I do remember some of it. I was 16 then.

Someday, people will think of 2008 as unbelievably long ago.

The grade at Naples Terrace is so steep in this hilly area that only a staircase can ascend it. LEFT: very old house with paint store on the ground floor.

Another one of Broadway’s dead-ends is a reminder of the days when streets were renamed, instead of sub-named with an extra sign. In 1977 when the DOT renamed a stub of west 236th Street for a Kingsbridge community leader, it merely removed the West 236th Stret sign and installed a sign saying “Tim Hendrick Place.”

You can’t go hungry along Broadway (especially if you prefer diner and pub fare); there’s Land and Sea, at Kimberley Place, and Stacks Tavern, near West 236th.

Taking a detour west on West 236th, past the 50th Precinct building, we find another spot named for a local hero, Lou Auger Square at Kingsbridge Avenue. John McNamara explains that Auger was a volunteer with the local Little League and the precinct for thirty years; Auger was recognized here in 1988, two years after his death.

An Auger Square parking lot shows a rusted 1960s-vintage light pole sporting a pair of General Electric M400 mercury vapor luminaires, and a lantern-style post, same vintage, at the gate.

Kingsbridge Avenue, which leads south to the original Kings Bridge site at the Bronx-Marble Hill border, mixes in a few late 19th and early 20th Century frame and wood buildings among the high-rises.

At Pauline’s Cabaret (Broadway and West 236th) I wonder what the entertainment is. Well, the 50th Precinct is next door. I haven’t eaten at the Riverdale Diner (Kingsbridge Avenue and West 238th) but I have been to the nearby Tibbett Diner.

The West 238th Street station resembles its West 231st counterpart. This one differs in that it boasts vintage 1970s boxy station-open indicators.

Hey, camera buffs: as you can see, I did not get an optimal shot of the MTA indicator (complete with old “M” logo). Using a Canon PowerShot S1-IS, I duly zeroed in on my target, and it looked fine on the display, but this was the blurry result. Why does the Canon behave this way, and what can I do while zooming to ensure myself a focused result?

I had mentioned lantern-type luminaires that were otherwise replaced on Broadway. They have been allowed to remain for a couple of blocks between West 239th and West 242nd. This style can also be found under the Liberty Avenue el, and have largely been phased out under the Roosevelt Avenue el, both in Queens.

It is appropriate that Broadway and West 240th Street is called Mike Quill Corner; it is near the entrance to the MTA’s 240th Street SubwayYards. Labor leader Quill (1905-1966) was the founder of the Transport Workers Union (TWU). He is, perhaps, best remembered for a quote after the TWU struck in January 1966 and Mayor John Lindsay had obtained a court injunction to force the union back to work. Quill and the TWU refused, and he was placed in jail for contempt. “The judge can drop dead in his black robes!” he railed. The strike lasted twelve days, and Quill had a fatal heart attack three days after it ended.

I was unfortunately unable to obtain a good photo of the playing field at Gaelic Park, West 240th Street west of Broadway. Manhattan College, which owns the park, keeps close wraps on views, since there’s an admission fee for most events here. Named in honor of Riverdale’s large Irish-American population, it has been home to soccer, softball and hurling for decades; my father attended matches here. It has been home to Manhattan College Jaspers soccer team since 1991, when the school purchased the grounds. There is a dance hall and cultural venue as well. In the 1970s Gaelic Park was a lively rock venue; the Grateful Dead, The Allman Brothers and Deep Purple have appeared here.

“Because it’s in the Bronx – and in a way, its not in the Bronx – it creates a space where things can happen. I was also amazed that an immigrant culture involved so many performances in everyday life. I mean, yes it was just a pub, and a field, but it was also a theater pit, and an arena – it can become all of these things, depending on the need and the occasion. No other ethnicity in New York has a cultural space that is anything remotely like it.” Irish Echo

A pair of relics at West 240th: a menagerie of ancient under-bridge luminaires can be found here, including a couple Westinghouse AK10 “cuplights” and their predecessors, at least in appearance, the 2801 Welsbach lume. These, unlike the cuplights, never had a glass diffuser. They were used on side streets and under overpasses mainly in the 1940s and 1950s. At right, a 1940s-vintage “Triborough Bridge” triangle sign. The Triboro lost its final “ugh” some time ago, and now [2008] the city will spend $4 million (during a severe money crunch) to remove all Triboro Bridge signs, replacing them with “Robert F. Kennedy Bridge” signs, honoring the late NY Senator who was shot and killed in June 1968 during a victory celebration following the California Democratic presidential primary.

Van Cortlandt’s Tail, likely named by former NYC Parks Commissioner Henry Stern, who was partial to whimsical names, is a 1/3 acre strip park between West 239th and West 240th on the east side of Broadway. On the map it appears to be a small “tail” of the massive Van Cortlandt Park on its southwest end.

Acre for acre, the Bronx has more parkland than any other borough, much of it in the huge 1150-acre Van Cortlandt Park, whose southwest entrance is at Broadway and West 240th Street; the 2770-acre Pelham Bay Park; and the 725-acre Bronx Park. The Parks Department installed a statue of a coyote here in 1998: coyotes have gradually assumed the ecosystem slot that was deserted by the departed timber wolf in upstate New York over the years, and a number of the canines have been spotted in the northern Bronx since the early to mid 1990s.