“Heaven,” postulated David Byrne, “is a place where nothing ever happens.” “Being just contaminates the void,” Robyn Hitchcock riposted some years later. In that spirit, it’s just possible that the three alleyways shown on today’s ForgottenPage are still here in New York, a town that has gradually sloughed off, paved over and eliminated its alleys over the decades, precisely because they are so little-known, inoffensive and little-trafficked that the developers have not even noticed they are there and have spared them. After all, that’s what has kept your webmaster working all these years: no one knows I’m there! Of course, with the impending full-scale makeover of the East Village’s Extra Place, these three unknowns may yet step forward and show us what they’ve got.

Edgar Street

Edgar Street, circled, 1867 Manhattan Dripps atlas; New York Public Library archive view of Edgar Street, seen from Trinity Place in the foreground and Greenwich Street, with its elevated train, in the background; and an Edgar Street corner — not sure if this is Trinity or Greenwich. At this time Edgar Street was 55 feet in length.

Throughout the years, several streets have competed for Shortest Street in New York City supremacy. There are many streets in New York, such as Mosco Street in Chinatown, that have been carved up, paved over, renamed, and shortened; some, such as Chestnut, that have been shortened repeatedly and as a final ignominy, eliminated completely (by the Al Smith Houses, the terminator of Chestnut, Oak, Batavia, New Chambers, and most of James and Oliver); and then there’s Edgar, which has been paved over and revived.

Edgar Street, which is presently 63 feet in length, was named for shipping merchant William Edgar, who at one point in his career owned the biggest shipping operation in the city.

LEFT: Edgar Street today, looking toward Greenwich. The old elevated, in existence between 1868-1940, has long vanished and the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel Trinity Place exit was completed here in 1953, with the massive parking lot on Greenwich showing up soon after.

2nd from LEFT: Edgar Street, looking toward Trinity Place. While Edgar remains, officially, the shortest through street in Manhattan at 63 feet in length, it’s actually rather busy these days, with two-way traffic and a center median. The red and blue buildings center right are likely the only structures that predate the construction of the tunnel in 1951. Edgar Street was transformed from the tiny alley seen in the photo on top to a traffic conduit between Greenwich and Trinity; the old Edgar was paved over, while the new Edgar was constructed.

Though no property has ever fronted on Edgar Street, the old version or the new version, the black and white Downtown Alliance signs yet grant it a 1-10 numbering, quite generously. Seen from the tunnel ramp, Edgar Street’s chief function is to act as a giant billboard.

I don’t know what hotel the sign points to.

A clutch of surviving Type 24M Corvington lampposts — the last few remaining in Manhattan from their 1910s installation — can be found on either side of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel approach. In the background we see the Western Union International building on Washington Street.

St. John’s Lane

The ceramic plaque at the Canal Street station on the #1 train, the 7th Avenue line, depicts a church with a towering spire, flanked by ample vegetation. Neither the church that is shown, nor the ample vegetation, is in evidence today. The church is the old St. John’s Chapel, which once stood on the east side of Varick Street between Beach and Laight Streets; the back side of the church faced the alley that was named for it. photo: nycsubway.org

By all accounts, St. John’s Chapel was an impressive edifice. The church was completed in 1803 by architect John McComb,and built by his brother, Isaac; McComb would go on to co-create NYC’s City Hall. St. John’s was design was based on that of St. Martin-in-the-Fields in London’s Trafalgar Square, with a portico supported by four Corinthian columns, and a 214-foot high spire. The interior featured freestanding fluted columns, and several years after construction, an ornamental ceiling, and an organ reclaimed from the British, who had captured it during the War of 1812.

St. John’s was constructed at a time when this location was far uptown and Trinity Church was attempting to gain a foothold in the then-wild territory. Trinity was sure to assert its overall dominance by naming St. John’s a ‘chapel,’ not a church. However, the church’s fortunes began to change during the 1860s; even then, this part of what would be called Tribeca by real estate marketers had begun to become dominated by the commercial and manufacturing concerns that would hold sway here until the mid-1990s. Trinity put St. John’s up for sale in 1866 and it was purchased by the very model of a mid-19th Century businessman — Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt — who razed the verdant grounds and constructed a large freight railroad depot across the street from the church, as shown on the map. The church soldiered on, in a deteriorated fashion, until Varick Street was widened as part of the IRT construction beginning in 1913 (that also gave rise to Seventh Avenue South). Today, warehouses and manufacturing concerns occupy the chapel’s old site, and approach ramps to the Holland Tunnel occupy the space of the old depot. The chapel is remembered by the subway mosaic and the once-country lane that ran along its back door.

In As You Pass By, Kenneth Dunshee writes of the area immediately surrounding St. John’s Chapel in the 1830-1860 era: The park and churchyard became noted for the variety and beauty of their trees. The beauty of the homes and the abundance of graceful shade made it a place of imposing grandeur. And the continuous line of balustrades framing the square and the houses and running up the stairs to the doorways added a peculiar aspect of European style and magnificence. Many of the homes had window panes that, in the course of time, acquired a violet tint, similar to those in old houses on Beacon Hill in Boston. The families of Alexander Hamilton, General Schuyler … and others of equal distinction lived in this residential oasis.

An unsuccessful battle to save St. John’s Chapel is described in Max Page’s The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900-1940 and the church is described in Oliver Allen’s Tales of Old Tribeca.

Narrow St. John’s Lane, seen from Beach Street (left) and Laight (right). In photo left, the American Thread Company building can be seen on the right.

Like every other street in Manhattan, no matter how narrow, St. John’s Lane has a sidewalk on both sides, and it’s so out of the way that it is still paved with Belgian blocks. The lane is illuminated by finned masts attached to the sides of its facing buildings, as there is no room for lampposts on the narrow sidewalks. In March 2009, it appeared as if the lane is being readied for repavement.

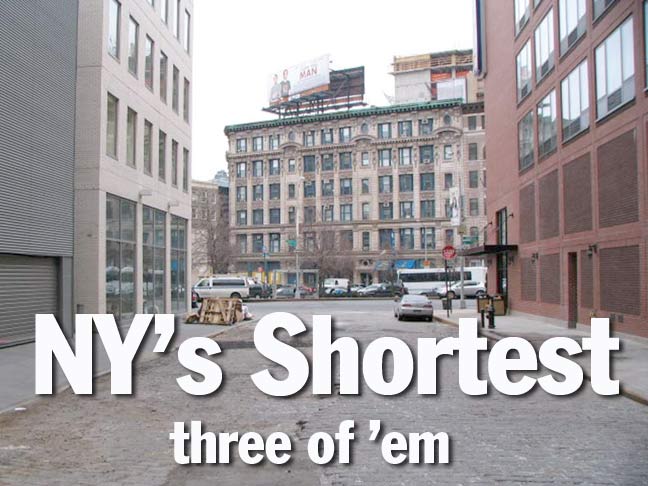

York Street

Soon after the British captured New Netherland from the Dutch in 1664, Colonel Richard Nicolls, who had led the armada in to New York Harbor, took possession of the territory and promptly renamed it for James, then Duke of York, the second son of King Charles I. Nicolls followed the “New” precedent set by the Dutch and so, New York was born as an entity.

“York”, itself, as a term, has a convoluted etymology. It was originally the term for yew tree, eburos, in one of the Celtic languages from western Europe that were displaced by the Italic and Germanic languages spoken by migrating and invading peoples from the east. A town named for the yew, Eburacon, was Latinized by the Romans to Eburacum. In ensuing centuries the name was simplified by Evoroc, and when Anglian conquerors arrived in the 300s and 400s, they heard Evoroc as sounding like their word for wild boar, eofor; ading the suffix, wic, village, the name became Eoforwic. Britain was again invaded some centuries later, this time by the Danes, or Vikings in popular fable, and the Danes, as the Angles had before them, adapted the place name to their own purposes and tendencies, and thus Eoforwic began to sound more like Yorvik. By Geoffrey Chaucer’s time in the 1300s, this had finally become York.

The lengthy story of why the town in the New World was renamed for the Duke of York is further told by George R. Stewart in Names on the Land, originally appearing in 1945 and reprinted in 2008, as is the etymological account of York itself.

Tiny York Street, tinier, in fact, than it originally was, is the only street in Manhattan named for its original British namesake. York Avenue on the east side was named for World War I hero Alvin C. York. Until 1823, York Street was the eastern extension of Hubert Street, and until 1928 it extended through to West Broadway. The southern extension of 6th Avenue for the new IND subway that year cost York Street about 40 feet now occcupied by the 6th Avenue roadbed. It may look shorter, but York Street, between 6th Avenue and St. John’s Lane north of Beach Street, is fully 103 feet long.

York Street, facing 6th Avenue, March 2009. It is considerably wider than St. John’s Lane.

One of the obscurest corners in the city is at St. John’s Lane and York Street. York, with its uneven Belgian blocks, is somnolent these days. A new development by Mexican-born architect Enrique Norten bears the name One York, possibly the first address located on the tiny alley, at least since its 1928 truncation. The brick building home to the new residences is a pre-Civil War brick warehouse.

page completed March 22, 2009