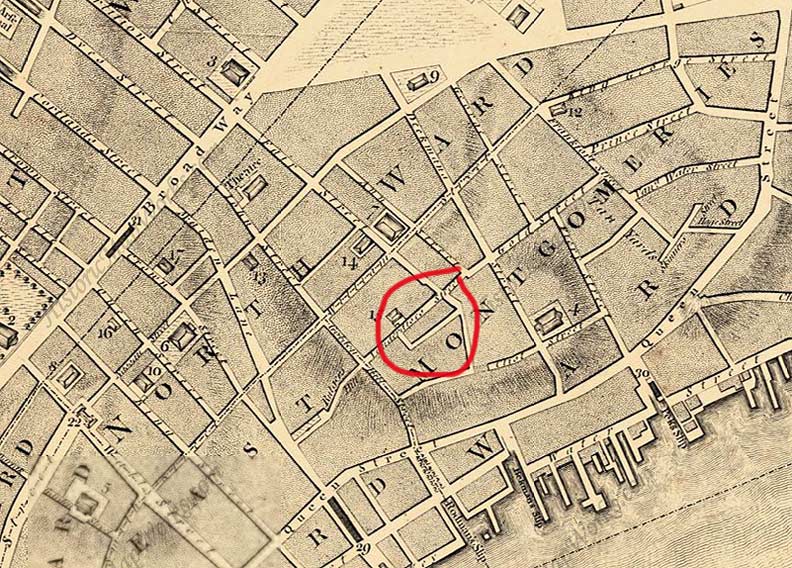

An L-shaped alley appears on maps of Lower Manhattan going back as far as 1776. At that early date we can already see streets with the same names as now, such as Broadway, Nassau, William, Beekman and Water. The basic street pattern is the same as today; even so, Queen Street has become Pearl and Fair was later extended to the East River and renamed Fulton, for the steamboat popularizer, Robert Fulton. Most of the streets on the northeast section of the map have been taken out by housing projects and the Brooklyn Bridge traffic approaches. As yet, the alley isn’t named on any maps.

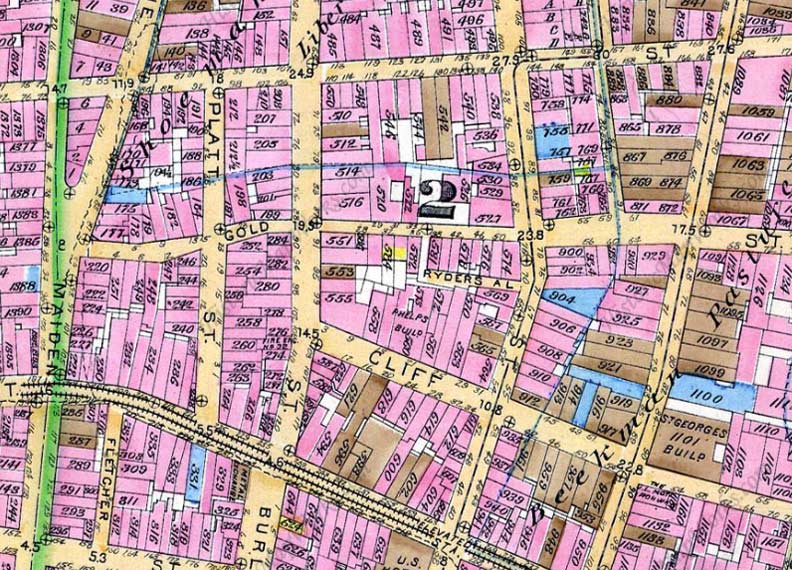

This map is labeled in Historic Map Works as 1830, but I think it’s actually the late 1790s, as the “long S” in Nassau and Rose Streets is still used, and Fair Street hasn’t become Fulton Street yet. (Also note I for J is still employed, as in “John.” That’s why Washington, DC has no “J Street”: “J” was not yet individualized from “I.”) For the first time, the alley is labeled “Ryders” or “Riders.” Again, note all the streets on the right side of the map we’ve since lost.

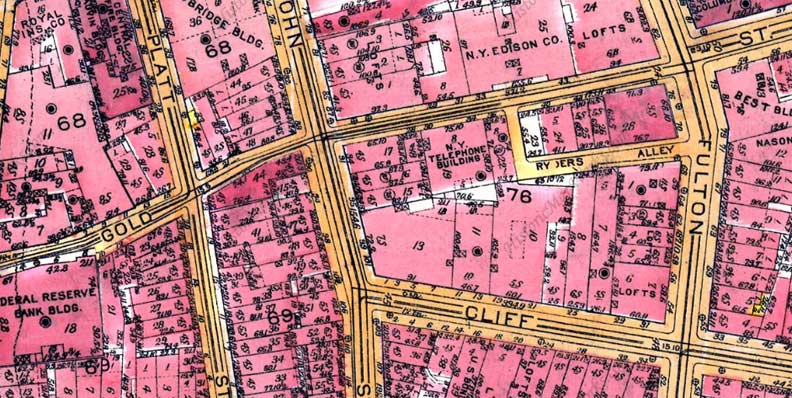

By 1867, the street pattern in the immediate area had crystallized pretty much into today’s, while the L-shaped alley still abides, running between Gold and Fulton Streets.

Ryders Alley appears between Gold and Fulton Streets in this 1885 map. It also shows the twisting nature and variable widths of lower Gold Street, a feature not usually noted on more modern print maps. The different colors of squares reflect different types of building materials; in 1885, brick was the preferred method.

For many years, the street pattern of NYC changed little. After 1924 (above) though, in many cities, not just NYC, many downtown streets were eliminated due to the “towers in a park” method followed by French designer/architect Le Corbusier and devotees such as NYC’s longtime traffic czar Robert Moses, who also destroyed a lot of the street patterns with bridge approaches, parkways and expressways.

Alleys were also where crime occurred, and nonhuman life forms hung out, as we’ll see.

So, who was the Ryder for whom the L-shaped lane was named? In The Street Book (Hagstrom, 1998) Henry Moscow professes not to know, but notes that prior to 1842, Ryder’s Alley was called Eden’s Alley. I’ll return to this presently, but I’ll also note that as you can see on the above examples, Moscow’s information may be incorrect.

Similarly, in Naming New York (NYU Press, 2001), Sanna Feirstein also could not find any attribution.

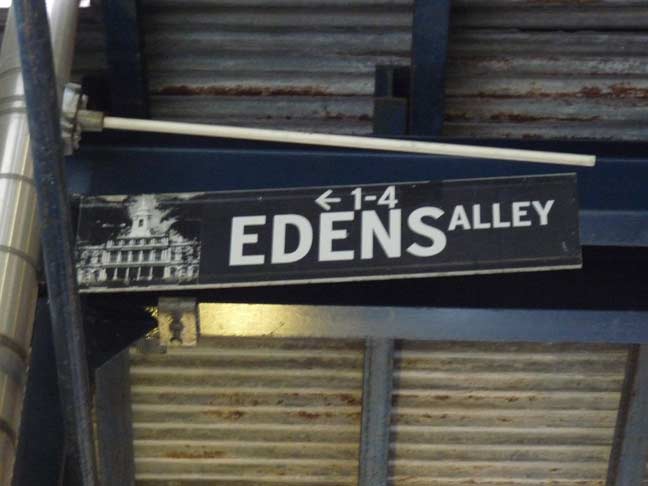

However, since 2001, when the Downtown Alliance installed new street signs in the region, the short jog of the alley that faces on Gold Street has been called Edens (Eden’s; the DA doesn’t believe in apostrophes). This apparently cites Moscow’s brief mention of Ryder’s formerly being called Eden’s, and the organization decided to split the difference, calling the Gold Street facing “Eden’s” and the Fulton Street facing “Ryder’s.”

So who was Eden? And who was Rider, or Ryder?

The answer can be found in, of all places, James Sullivan’s 2004 study of Manhattan mammalian vermin, Rats (Bloomsbury, 2004). In fact, an entire chapter is devoted to Edens Alley (I’ll do without the apostrophe, as Sullivan does). Sullivan studied rats extensively on the L-shaped alley, since on Fulton Street it borders Chinese and fast food restaurants, which attracted legions of the rodents.

Sullivan’s meticulous research concluded that the alley first appeared around 1740, and he found in records of city proceedings from the late 1600s that a John Rider ordered paving stones for his street. A John Rider was also a prominent British-born barrister living in lower Manhattan at this time. The lane has been known as Rider, Rudder, Ridder and at last, Ryder’s.

Edens Alley facing Gold Street

Sullivan found that a prosperous New Yorker named Medcef Eden (he is identified as a brewer in other accounts) lived in Rider Street, or today’s Ryder’s Alley, which likely was a bucolic, tree-lined route in the late 1700s when he was around. In facet Eden owned most of the property facing the lane, as many as twenty buildings total. Eden was originally from Yorkshire, England, and after coming to NYC he became a close friend and associate of Aaron Burr. He owned a large parcel uptown, called the Eden Farm, which was later owned by John Jacob Astor; in the early 1900s it was developed as Times Square. As for his unusual first name, I’d have to guess it’s a variant spelling of the commoner Metcalf.

Ryders Alley (foreground) meets Edens Alley

As for the mixup between the L-shaped alley’s name, Sullivan says that until 1833, it was entirely Ryder’s Alley, but the short section facing Gold was renamed for Eden that year, reverting to all Ryder’s in the early 1900s until the Downtown Alliance re-renamed the shorter section Edens Alley in 2001. Got it?

Ryders Alley facing Fulton Street. I doubt these are the original paving stones ordered by John Rider many years ago.

Ryders Alley, looking back toward Edens Alley.

I shot this photo of a painted wall ad at Ryders Alley and Fulton Street several years ago. The ad has since been obscured by a larger ad.

5/20/15

4 comments

I lived in 70 Fulton st. encompassed by both sections of the alley. Recently an atrocious curb modification was slopped directly onto the (older than not) paving stones along Ryder alley. Hard to imagine why 70 Fulton st has escaped development all these many years. Directly across from the Eden’s leg of this historic alley is 33 Gold st. Adorning the entrance of this building is a gorgeous sign of unique font, it reads “Excelsior Power co. bldg.” 1888. Some poking about internet .com will introduce you to an engineer called Leo Daft, foundational element in development and distribution of commercial electricity for the city. New York’s earliest electric street lights still adorn the facade, this contributed in 33 Gold st. becoming a heritage site in the late 90’s. Permanent scaffold has obscured these elements for the last 20 years, coupled with Excelsior Electric’s absorption into the Edison myth, resulting in a fascinating section of world history fading beyond distinction.

The little-known Battle of Golden Hill (January 19, 1770) was a skirmish between the Sons of Liberty and occupying British soldiers. It took place here at Eden’s Alley and Gold Street.

This event was one of the earliest bloody clashes leading to the Revolution. Four Liberty Poles in succession were erected in City Hall Park by the Sons of Liberty. But the poles had all been rapidly cut down by the British. In defiance, the Sons of Liberty kept replacing the poles. In 1769, the British dissolved the New York Assembly because the Assembly refused to enforce the British Quartering Act (an Act requiring the colonies to pay to house and feed the occupying British Army). In protest of the dissolution, the Sons of Liberty hoisted another Liberty Pole and published a broadside entitled: “To the Betrayed Inhabitants of the City and Colony of New York.” At this, the British blew up the Liberty Pole and published their own handbills declaring the Sons of Liberty the “real enemies of society” who “thought their freedom depended on a piece of wood.” The Sons of Liberty attempted to stop the Soldiers from handing out the handbills and a bloody scuffle ensued. No one was killed, but at least one soldier was seriously injured. British and American blood was shed.

This extremely important, but little-known, New York event on January 19, 1770 between colonists and the British Army predated the Boston Massacre (March 5, 1770) by six weeks. Eden’s Alley is the site of a major event in American history. Although this site once bore a historic marker, the plaque was lost during a construction project and was never replaced. The history associated with this place has fallen into obscurity. This entry is made in the hope that the courage and persistence of the Sons and Daughters of Liberty is not forgotten, and that history is honored, even in small alleys.

Jan Reyndersen, is noted as living at No. 13 South Williams Street, (now No. 16, on the North side) from 1655-1658. This may have been the painter, Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) of Delft, whose real name was Jan Reijnierszoon. Early maps, in his style, calligraphy and some signed; include the Manatus Map, the Block Figurative Map and the Castello Plan (attributed to Jacques Cortelyou), suggest that he was a cartographer. He may have be the Jan Ryder, who ordered the pavers for Ryders Alley. My research on the subject, of Vermeer coming to the New Netherlands, is detailed in a series of articles on Academia.com.

Sorry, typo, “He may have been the Jan Ryders, who ordered the pavers for Ryders Alley.” That’s why the name is spelled with an “s” at the end; which stands for “szoon”.