Saturday, January 29th was sunny, cold and blustery, about what you’d expect on that date. Snow and ice crunched underfoot as over a dozen Forgotten Fans set out from the Lenox (Malcolm X Boulevard) Avenue and 125th Street IRT station.

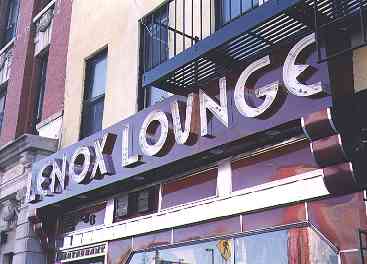

The Lenox Lounge displays the best in neon signs on the outside and the coolest jazz on the inside.

Bypassing the usual Harlem landmarks such as the Apollo (always worth a visit), we wanted to seek out the items that don’t find their way into the newspaper articles and most of the guidebooks. Our first stop was to a Harlem landmark that hasn’t seen active service since about 1870.

The tower is still in virtually the same condition it was when it was constructed, except a fence has been added around the exterior and the observation deck has been removed.

Forgotten Fans (above) gather at the Marcus Garvey Park Fire Watchtower. The tower is in need of repair but miraculously, is still standing with its bell intact.

Mount Morris Park, set on a rocky outcropping between East 120th and East 124th Street, interrupts the northen progress of Fifth Avenue, which runs south from here all the way to Washington Square Park.

It has always been parkland ever since this area was settled. Long before the street grid marched north, followed by brownstones, streetcars and eventually, elevated trains and subways, land here was set aside for a park. Mount Morris Park was christened in 1842. (In 1973 it was renamed for black nationalist Marcus Garvey.) The park, it should be noted, is surrounded on three sides by magnificent brownstone buildings.

Doric columns support a platform and observatory (now removed). A spiral staircase ascends to the observatory and the bell hangs from bowed iron girders.

In the early 1800s, there was no such thing as electric lights, radio or fire alarms. In general, when a fire broke out, you had to make a lot of noise on your own to alert the local population.

Blazes were fought by volunteer fire departments, which were poorly coordinated and organized, until 1865, when the New York state legislature replaced the volunteer companies with the Metropolitan Fire Department. (The Fire Department of New York would succeed it in 1870.)

The tower that remains here was built by Julius Kroehl in 1856. Until the fire companies acquired a telegraphic alert network in 1874, they relied on watchmen in lookout towers that were built on hills in Manhattan.

Many of these towers were made of wood, and did not stand up to the elements over the years. This one is made of cast iron, while the design is based on earlier towers by James Bogardus, who had built earlier such towers on 33rd street near 9th Avenue and Spring Street near MacDougal.

Other famed fire towers were the “Mechanics Bell” which stood from 1831 to 1873 in East River shipyards, and the Jefferson Market bell tower at Sixth Avenue and 9th Street, which lasted from 1832 to 1877, to be replaced by the Gothic building which currently stands there.

Following Fifth north from Marcus Garvey Park, and turning left at West 130th Street, we arrived at the magificent Astor Row.

Comprising the southern part of West 130th Street between Fifth and Lenox, Astor Row, built by architect Charles Buek between 1880 and 1883, features an extreme rarity in Manhattan: houses with porches!

Built on land owned by William Astor (great grandson of fur entrepreneur John Jacob Astor and scion of his real estate empire), Astor Row is made up of 28 brick houses, some attached, some not.

Though not all the Astor Row houses are in the terrific shape this one is in, since 1992 great strides have been made toward rehabilitating them. In that year, the NYC Landmarks Convervancy in association with the Landmarks Preservation Commission and the Abyssinian Development Corporation began the ongoing project to reverse the deterioration and restore Astor Row.

This brick building on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Blvd, was a major mecca of Harlem nightlife in the 1930s in its incarnation as the Renaissance Ballroom. The “Renny” offered dancing, cabaret acts and the finset bands of the era, including those of Vernon Andrade, Fletcher Henderson and Chick Webb.

The adjoining Renaissance Casino was the home court of the 1920s Harlem Rennies, the first all-black professional basketball team, which racked up a 2588-592 record against other local competition.

Moving on to West 138th and West 139th between Powell and Douglass Blvds. we find the King Model Houses, more popularly known as Striver’s Row.

Called “two of the most spectacular streetscapes in New York City” by Andrew Dolkart and Gretchen Sorkin in Touring Historic Harlem, 146 rowhouses and three apartment buildings were built by developer David King Jr. beginning in 1890.

Appointed with elegant woodwork and modern plumbing (then in its infancy in NYC in 1890), the buildings employ designs from the most illustrious architects of the period. Subtle variations in each building nreak up monotony as does the presence of handsome iron gates that open up to allow access to service alleys–very unusual in New York City.

How did Striver’s Row get its name?

It is a tribute to the fact that in the 20s and 30s the King Model Homes were the residence of several prominent Harlemites, notably Vertner Tandy, the first commissioned African American architect in New York State; W.C. Handy, “father of the blues”, composer and compiler of African American folk music traditions; Fletcher Henderson, the jazz pianist and orchestra leader; and Harry Wills, a top heavyweight contender who never got to fight for the title due to racism in the boxing hierarchy.

This gateway leads to a service alley behind the King Model Homes, but in the days before horseless carriages it also served as a place to park your mount. Note the original “walk your horses” sign.

Our tour later moved on to the Hamilton Grange and the Morris Jumel Mansion. Unfortunately, my camera jammed at this point, and I don’t yet have photos from our visit, but when I do, I’ll be sure to post them.

Of course we scratched the mere surface of what Harlem has to offer, Forgotten or otherwise, and a return visit or twelve is on the eventual agenda. Meanwhile, here’s a terrific Salon Magazine article about Harlem.

Sources:

Touring Historic Harlem, Four Walks In Northern Manhattan, Andrew S. Dolkart and Gretchen S. Sorin, NY Landmarks Conservancy 1997